On the eve of the First World War, the Ottoman Empire commanded an expansive territory measuring 1.7 million square kilometres, encompassing present-day Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Iraq, and sections of the Arabian Peninsula. Its populace exceeded 23 million, with three-quarters residing in Anatolia. Despite undergoing substantial economic transformation and growth during the 19th century, particularly in the last two decades, the Empire remained notably less affluent than European nations in terms of both cumulative and per capita real gross domestic product (GDP).

In 1913, the Ottoman GDP, evaluated at current prices, stood at £220 million, translating to approximately £10 per capita. When adjusted for purchasing power parity and 1990 prices, these figures equate to $25.3 billion and $1,100, respectively. A comparative analysis reveals that the respective total and per capita GDP numbers in the said year were $226.4 billion and $4,921 for the United Kingdom, $257 billion and $676 for the British Colonies, $138.7 billion and $3,485 for France, $257.7 billion and $1,488 for Russia, $244.3 billion and $3,648 for Germany, $100.5 billion and $1,986 for Austria-Hungary. It is, however, imperative to acknowledge that, in terms of GDP, both total and per capita, the Ottoman Empire surpassed its southern neighbours, namely Egypt and Iran.

Why did the Ottoman Empire remain behind Europe?

The territorial expansion of the Ottoman Empire concluded in the late 16th century, leading to a cessation in the inflow of funds to the Ottoman treasury. Simultaneously, the emergence of the New World discoveries caused a shift in the global trade dynamics, diminishing the Mediterranean's erstwhile pivotal role. Compounding this, the influx of gold and silver from the Americas disrupted the delicate equilibrium of money and prices in the worldwide economic landscape.

The resultant conflicts and internal upheavals placed a substantial strain on Ottoman finances. Distinct from the prevailing powers of the era, the Ottomans were engaged in incessant struggles not for capital accumulation but for their very survival. The Empire found itself unable to keep pace with the transformative forces of the Industrial Revolution, which commenced in Britain, ushering in novel production methods and technologies.

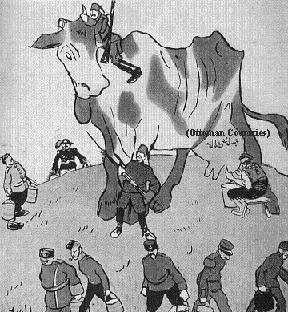

European nations, benefitting from special privileges within the Empire, systematically penetrated Ottoman markets with their export commodities, thereby causing the gradual demise of indigenous producers. The economic challenges faced by the Ottoman Empire were further compounded by its inability to adapt to the evolving industrial landscape and the encroachment of foreign competitors into its markets.

During this historical period, the Ottoman administration grappled with an inability to regulate public finance, foreign trade, and monetary circulation. Financial shortfalls necessitated reliance on extensive foreign borrowing, engendering a pernicious cycle. This predicament arose as the economic and social framework of the Empire precluded the formulation and execution of comprehensive macroeconomic strategies conducive to overarching economic stability.

The prevailing structures of capital ownership and utilization proved unsuitable for the pursuit of an economic growth agenda, thus exacerbating the conundrum. A pronounced incongruity between the state apparatus and the foundations of capital accumulation further compounded the challenges faced.

The indigenous reservoirs of capital proved insufficient to sustain the economic machinery. The tax regimen exhibited inefficiencies and imbalances, disproportionately burdening rural taxpayers, while concurrently extending favourable exemptions to foreign companies and ethnic minorities. Such a state of fiscal affairs underscored a palpable inadequacy in the established financial architecture, hindering the equitable distribution and allocation of economic resources.

The monetary system of the Ottoman Empire presented considerable challenges as well. While coins and banknotes from the Banque Impériale Ottomane circulated, foreign currencies were also prevalent. In 1881, the definition of a golden Ottoman Lira was established at 7,216 grams of gold, equating one Lira to 100 Piasters. The silver Mecidiye coin held a value of 20 Piasters. Over time, the devaluation of silver and the introduction of copper Mecidiye coins resulted in the emergence of a bimetallic system. Discrepancies in monetary units prompted the melting and re-minting of coins, fostering widespread speculation on currency values.

The monetary system of the Ottoman Empire presented considerable challenges as well. While coins and banknotes from the Banque Impériale Ottomane circulated, foreign currencies were also prevalent. In 1881, the definition of a golden Ottoman Lira was established at 7,216 grams of gold, equating one Lira to 100 Piasters. The silver Mecidiye coin held a value of 20 Piasters. Over time, the devaluation of silver and the introduction of copper Mecidiye coins resulted in the emergence of a bimetallic system. Discrepancies in monetary units prompted the melting and re-minting of coins, fostering widespread speculation on currency values.

Foreign capital flowed through two primary channels. The first source was foreign debt, initiated during the Crimean War and progressively growing to an unsustainable magnitude. The second source comprised foreign investments, concentrating on sectors promising swift profitability. The cumulative foreign capital in the Ottoman economy at the time amounted to 234.1 million Liras. Of this sum, 149.5 million Liras constituted foreign debt, with the remainder allocated to foreign investments. The railway construction sector attracted the highest investment at 53.3 million Liras, trailed by banking and insurance with 8.2 million Liras, industry with 6.5 million Liras, public utilities with 5.7 million Liras, port construction with 4.7 million Liras, and mining with 3.6 million Liras. Regarding return rates, banking and insurance stood out with a 10.9 percent rate of return, followed by foreign debts at 8.7 percent, industry at 8.6 percent, and mining at 6.4 percent. French capital constituted 44 percent of foreign investments, German capital accounted for 34 percent, British capital for 17 percent, while Belgian and American capital comprised the remaining shares.

Agriculture and Industry

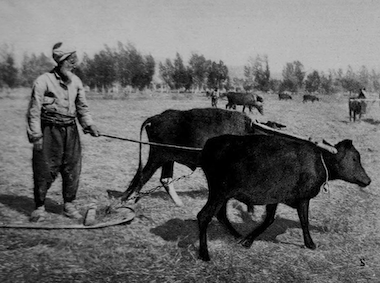

In 1913, the Ottoman economic landscape exhibited a predominant agrarian character, with agriculture constituting 48 percent of the GDP. The structural dynamics of land ownership within the Empire had undergone significant transformations during the 19th century. Formerly, all agricultural lands were under state ownership, and plots were leased to civil servants tasked with tax collection and soldier conscription. The central government exercised comprehensive control over economic facets, including production and distribution. Nonetheless, the efficacy of this system diminished over time. The Land Law of 1858, known as Kanunname-i Arazi, marked a pivotal shift by embracing the principle of private ownership.

At the heart of production lay the family enterprise, typically equipped with a pair of oxen and a modest plot for cultivation. Concurrently, larger-scale enterprises coexisted alongside peasants devoid of personal oxen and land. The latter group functioned as sharecropping tenants, rendering services to larger landowners. According to official statistics from 1913, 87 percent of peasant families cultivated some land, collectively claiming ownership of 35 percent of all arable land. In contrast, 8 percent of peasant families lacked any land, while a minority of landlords, constituting 5 percent of all families, possessed a substantial 65 percent of the land. This restructuring of land ownership illuminated the nuanced interplay between familial agricultural units, sharecropping arrangements, and the concentration of land among a select group of proprietors.

Agricultural pursuits predominantly transpired in coastal regions rather than the hinterlands, influenced by a dearth of labour, transportation means, and arable expanses. Farmers primarily engaged in cultivating cereals and subsistence crops underwent a transition to cash crops like tobacco and cotton, alongside industrial raw materials during the 19th century, owing to agricultural commercialisation. Preceding the conflict, cereals occupied 80 percent of agricultural land, cash crops claimed 7 percent, vegetables secured 7 percent, and fruit held a 4 percent allocation.

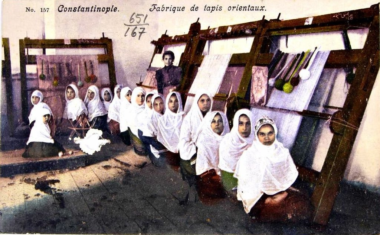

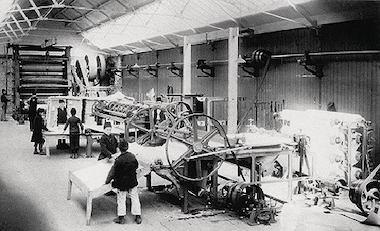

Manufacturing activity in this period was largely based on artisan forms. In 1913, the industrial sector's contribution to the economy amounted to a mere 12 percent. This disparity can be attributed to the Empire's lag behind Europe in the Industrial Revolution, with modern factories emerging only towards the late 19th century. The Ottoman Industrial Census of 1913, encompassing solely West Anatolia, reported 600 manufacturing establishments employing over 10 workers, and merely 60 establishments exceeding 100 workers. Aggregate manufacturing employment stood at 35 thousand, constituting a meagre 0.2 percent of the total population. Textile, food processing, construction materials, paper, and printing predominantly accounted for this employment, with 55 percent of establishments situated in Istanbul and 22 percent in Izmir.

Apart from the limited domestic market and technological constraints, industry's stagnation was exacerbated by the formidable competition posed by imported goods. In the 1830s, the Ottoman government entered various international agreements, stipulating ad valorem tariffs as low as 5 percent, with the inaugural accord inked with Britain in 1838. This facilitated the unhindered influx of foreign goods into Ottoman markets. Internal commerce of domestically manufactured items, meanwhile, incurred an 8 percent customs tax, which was rescinded in 1908. Import tariffs were subsequently raised to 15 percent prior to the war. A 1913 legislation aimed at fostering industrial development introduced incentives like tax exemptions and land allotments, eliciting some advancement in private industrial entrepreneurship.

The Ottoman industrial sector, primarily rooted in artisanal modalities and guild frameworks, proved inadequate in adapting to the requisites of an industrial revolution. Following the liberalization of the economy, the industry faced substantial setbacks. Ownership of extant enterprises predominantly rested in the hands of non-Muslim minorities and foreigners. These entities perceived themselves as detached from the communal structure and the political decision-making apparatus. Consequently, a pervasive lack of confidence impeded efforts to augment production.

The services sector, exhibiting relative profitability, acted as a deterrent to the allocation of resources towards industrial pursuits. In an endeavour to meet military requirements, the Ottomans instituted industrial facilities through public investment. They implemented measures to foster industrial development and, in subsequent years, introduced incentives. Nevertheless, these initiatives achieved only a modest impact on industrialization.

Mining, Railroads and Foreign Trade

Mining, a pivotal sector, experienced substantial growth in the late Ottoman era primarily due to significant foreign investment, predominantly originating from France. Coal extraction served domestic needs, with the surplus earmarked for exportation. In 1911, the Ottoman Empire produced 904 tonnes of coal, 17.5 tonnes of chromium, 13.5 tonnes of borax, 11.5 tonnes of lead, and approximately 1,000 tonnes of copper. Notably, 75 percent of the mining output in that year was under foreign ownership. The Mining Law (Maden Nizamnâmesi) of 1906 permitted foreigners to lease mines for a duration of 99 years, subject to a government-imposed rent for the land and a variable extraction fee. This fee ranged from 1-5 percent for coal, copper, and lead, and 10-20 percent for chromium, borax, and oil. Legislative provisions favoured foreign capital, leading to substantial benefits accruing to foreign companies as the sector expanded.

Simultaneously, railway construction emerged as the most enticing sector for foreign investment within the Ottoman Empire. Foreign enterprises secured prolonged operational rights, often extending between 70-100 years, accompanied by profit guarantees. Prior to the outbreak of war, Germany held a commanding 57 percent share of railroad investments. Railway construction amplifies the production volumes of essential raw materials, particularly iron and steel, while at the same time it establishes connectivity between interior regions and markets. In the Ottoman Empire, the first effect was hindered by the absence of a domestic iron-steel industry. Consequently, the genuine contribution of railways to economic development manifested in their role as conduits linking agricultural production centres with marketplaces, fostering connectivity between West Anatolian agricultural output and export markets.

Ottoman foreign trade policies historically adhered to the strategy of restricting exports and augmenting imports, a practice that confounded European observers. This approach sought to amplify the domestic market's product output, thereby ensuring price stability. Consequently, the Ottoman economy perennially experienced a trade deficit. In 1840, the deficit amounted to 1.9 million Liras, with an export-to-import ratio of 75.3 percent. By 1912, this deficit had expanded to 16.7 million Lira, accompanied by a decline in the export-to-import ratio to 54.1 percent.

Exported commodities, notably agricultural products such as tobacco, cotton, hazelnuts, silk, and figs, along with coal, formed the principal components. Conversely, the primary items imported included clothing, woven materials, fuel, sugar, and flour. Throughout this period, the escalation of export prices lagged behind that of import prices, further compounding economic challenges.

Guns or butter? Or neither?

Before the onset of the conflict, Ottoman manufacturing of war-related materials, such as military vehicles, firearms, and ammunition, remained notably limited, resulting in a considerable reliance on imports. The production of iron, steel, chemicals, and the refinement of petroleum exhibited insignificance. The only manufacturing establishments of guns and ammunition the Empire had were one cannon and small arms foundry, one shell and cartridge factory and one gunpowder factory, all located just outside Istanbul.

The Empire, prior to the war, maintained a surplus of coal, even functioning as a net exporter. However, challenges arose during the conflict when Ereğli coal mines fell victim to Russian bombardment. This unforeseen circumstance disrupted the coal supply, creating a substantial hurdle.

Despite a considerable influx of foreign investment in railroad construction during this period, the existing railroad network proved insufficient to meet wartime demands. The total length of the railway system stood at a mere 6,000 kilometres, with Eastern Anatolia notably devoid of any railroads. An agreement with the Russians stipulated consultation before constructing railroads, leading to a lack of rail connections between Anatolia, Syria, and Palestine. It was not until January 1917 that tunnels in the Taurus Mountains and Southern Anatolia were completed. Prior to this, troops and materials had to be unloaded at the final station, transported by road, and subsequently re-loaded onto trains where railway services resumed. Simultaneously, poorly maintained land roads dictated a reliance on draught animals for transportation.

The Ottoman Empire, unequivocally, faced economic unpreparedness compared to most other nations engaged in the prolonged, multi-front conflict. Despite inherent shortcomings and disadvantages, the Ottoman economy sustained the war effort until its conclusion, avoiding a complete financial collapse.

![]()

Sources consulted:

- Akyıldız, A., “Para Pul Oldu: Osmanlı’da Kağıt Para, Maliye ve Toplum” (Paper Money, Public Finance and Society in the Ottomans), İletişim Yayınları, Istanbul, 2003.

- Eldem, E., "A History of the Ottoman Bank", Ottoman Bank Historical Research Cente, Istanbul, 1999.

- Elmacı, M.E., “İttihat Terakki ve Kapitülasyonlar” (Committee of Union and Progress and the Capitulations), Homer Kitabevi, Istanbul, 2005.

- Esin, T., "Osmanlı Savaşı'nın İktisadî Aktörleri 1914-19" (The Economic Actors of the Ottoman War 1914-19), Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, Istanbul, 2020.

- Geyikdağı, V.N., “Osmanlı Devleti’nde Yabancı Sermaye 1854-1914” (Foreign Investment in the Ottoman Empire 1854-1914), Hil Yayın, Istanbul, 2008.

- Issawi, C., "The Economic History of Turkey, 1800-1914", University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1980.

- Pamuk, Ş., “Osmanlı Ekonomisinde Bağımlılık ve Büyüme 1820-1913” (Dependence and Growth of the Ottoman Economy 1820-1913), Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, Istanbul, 1994 (first published in Ankara, 1984)

- Toprak, Z., “İttihad-Terakki ve Cihan Harbi: Savaş Ekonomisi ve Türkiye’de Devletçilik 1914-1918” (Committee of Union and Progress and the World War: War Economy and Etatism in Turkey 1914-1918), Homer Kitabevi, Istanbul, 2003.

- Yorulmaz, N., “Büyük Savaşın Kara Kutusu: 2. Abdülhamid’den 1. Dünya Savaşı’na Osmanlı Silah Pazarının Perde Arkası” (The Black Box of the Great War: Behind the Scenes of the Ottoman Arms Market from Abdulhamid to the First World War), Kronik Kitap, Istanbul, 2018.

PAGE LAST UPDATED ON 30 DECEMBER 2023