Wartime exigencies posed formidable challenges to the Ottoman Empire's sustenance. Despite its agrarian disposition, the empire found itself reliant on imported food supplies, even during periods of peace. This inadequacy stemmed from the fact that the agricultural sectors, while meeting local demands, could not generate a surplus substantial enough to cater to the extensive needs of Istanbul, a major consumption hub. In the preceding quarter-century, only on four occasions did Istanbul receive a satisfactory allotment of food from its hinterlands. Further compounding the issue was the prohibitively elevated cost of production, rendering it arduous for local producers to competitively contend with imported commodities.

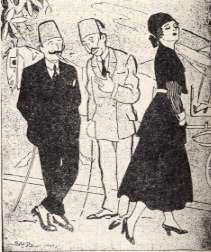

- "I have been chasing her for two months; I have offered her an automobile, but she doesn't care."

- "You should have offered her two packs of sugar; then she would be all yours!" Cartoon by Sedat Simavi • "Yeni Zenginler", 1918

The advent of the First World War exacerbated the predicament. A precipitous decline transpired in both production and imports, juxtaposed against a heightened demand for sustenance. The conventional ebb and flow of the market could no longer be relied upon to ensure the provisioning of food across diverse segments of Ottoman society. Concurrently, the transportation infrastructure proved inadequately equipped to cope with the exigencies and stresses imposed by wartime conditions in an efficient manner.

The government formulated a series of policies to address prevailing challenges. On one front, it intervened in the market to augment food production, concurrently striving for a more just distribution of available resources. The latter objective materialised through the implementation of a comprehensive rationing system in Istanbul. Initially, the responsibility for provisioning food supplies in the capital rested with the Istanbul municipality. However, it soon became apparent that the municipality was ill-equipped to execute this task efficiently.

In January 1915, Kemal Bey (aka Kara Kemal), a notable figure within the ruling Committee of Union and Progress, assumed leadership of the Tradesmen’s Union (Esnaf Cemiyeti), tasked with overseeing food provision. Kemal Bey wielded unrestricted authority over all food-related matters, including the power to requisition mills and bakeries for the collective good. Subsequently, the establishment of a Food Board in July 1916 marked a significant development within the evolving framework. By this juncture, the Ottoman Empire had implemented a system of "war agriculture."

It was in 1916 that the government comprehended the critical nature of the food situation, recognizing its potential detriment to ongoing war efforts. A comprehensive campaign ensued, aiming to augment food production. The legal underpinning of this initiative took shape with the enactment of the Law of Agricultural Service (Mükellefiyet-i Zirâiye Kânûn-ı Muvakkati) in October 1916. This legislation mandated large corporations in urban areas to facilitate necessary equipment and labor, cultivate specified amounts of land, and mandated all farmers to cultivate a minimum area. Additionally, it compelled all able-bodied individuals not engaged in military service to participate in agricultural endeavours.

The implementation of measures, coupled with additional budgetary allocations to support agriculture, exerted a positive influence on production levels. Nevertheless, their efficacy was belated, attributable to the negligent depletion of human lives and draft animals engaged in agriculture over two years. The primitive and deficient nature of the means of production, compounded by territorial losses and proximity to war fronts, had further exacerbated the exhaustion of resources in numerous regions.

The transportation of food supplies from Anatolian production centres to Istanbul encountered impediments. The railway connecting central Anatolian plains to Istanbul and the ships linking Black Sea ports with the imperial capital faced space constraints. Government intervention became imperative to optimally allocate the scarce transportation resources. This intervention fostered nepotism, affording the Committee of Union and Progress government the discretion to selectively designate a minor cohort of merchants for the privilege of supplying Istanbul. Permits were exclusively granted to Muslim-Turkish entrepreneurs affiliated with the party, aligning seamlessly with the Turkish economic nationalism espoused by the wartime government.

In response to the imperative of provisioning the capital city during the war, the government initiated direct procurement of agricultural produce from Anatolian farmers. There were distinct stages characterizing the evolution of the government's procurement policy and the corresponding reactions of the farming populace.During the initial phase, in the early stages of the war, the government primarily relied on market mechanisms for the supply of food to Istanbul and other urban centres. However, the emergence of shortages, particularly acute in eastern Anatolia, northern Syria, and Lebanon, compelled governmental intervention in the food procurement process. Subsequently, all producers were mandated to retain only sufficient produce for seed and familial subsistence. The surplus was to be relinquished to the government at predetermined prices, which were below prevailing market rates. Notably, this policy adversely impacted producers, prompting recourse to covert practices such as concealing and withholding harvests from government agents. Consequently, these clandestine actions exacerbated the dearth of food supplies to Istanbul and other urban areas.

Amidst escalating challenges, the government transitioned to the next stage in 1917. Under the new paradigm, producers were obligated to surrender a stipulated portion of their yield to the government, either as an in-kind tax or at a fixed price below the prevailing market rate. The remainder could be freely sold to any interested party. The reinstatement of market dynamics instigated a surge in production as producers sought to capitalise on the lucrative market prices. This policy framework persisted until the culmination of the war in 1918 when the Food Ministry was established, with Kemal Bey assuming the ministerial role.

-In summary, food scarcity and hunger were not solely attributable to the availability of food; rather, disparities and injustices in food distribution within societal factions exacerbated the issue. Arguably, among the conflicting entities, the Ottoman Empire bore the brunt of the food predicament. This was not solely attributable to the heightened susceptibility of Turkish agriculture to wartime disruptions, but also stemmed from the government's inability to address these challenges, as the predicament resided in deficient distribution, wasteful resource allocation, indiscriminate experimentation, and a monopoly predominantly serving the vested interests of those in close proximity to the government. The genuine public welfare remained largely unapprehended by those in positions of authority, who manifested indifference towards endorsing profiteering in the food sector. It is imperative to recall that a state of famine pervaded all regions of the Ottoman Empire during the final two years of the war.

![]()

Sources consulted:

- Akyıldız, A., “Para Pul Oldu: Osmanlı’da Kağıt Para, Maliye ve Toplum” (Paper Money, Public Finance and Society in the Ottomans), İletişim Yayınları, Istanbul, 2003.

- Eldem, E., "A History of the Ottoman Bank", Ottoman Bank Historical Research Cente, Istanbul, 1999.

- Elmacı, M.E., “İttihat Terakki ve Kapitülasyonlar” (Committee of Union and Progress and the Capitulations), Homer Kitabevi, Istanbul, 2005.

- Esin, T., "Osmanlı Savaşı'nın İktisadî Aktörleri 1914-19" (The Economic Actors of the Ottoman War 1914-19), Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, Istanbul, 2020.

- Geyikdağı, V.N., “Osmanlı Devleti’nde Yabancı Sermaye 1854-1914” (Foreign Investment in the Ottoman Empire 1854-1914), Hil Yayın, Istanbul, 2008.

- Issawi, C., "The Economic History of Turkey, 1800-1914", University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1980.

- Pamuk, Ş., “Osmanlı Ekonomisinde Bağımlılık ve Büyüme 1820-1913” (Dependence and Growth of the Ottoman Economy 1820-1913), Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, Istanbul, 1994 (first published in Ankara, 1984)

- Toprak, Z., “İttihad-Terakki ve Cihan Harbi: Savaş Ekonomisi ve Türkiye’de Devletçilik 1914-1918” (Committee of Union and Progress and the World War: War Economy and Etatism in Turkey 1914-1918), Homer Kitabevi, Istanbul, 2003.

- Yorulmaz, N., “Büyük Savaşın Kara Kutusu: 2. Abdülhamid’den 1. Dünya Savaşı’na Osmanlı Silah Pazarının Perde Arkası” (The Black Box of the Great War: Behind the Scenes of the Ottoman Arms Market from Abdulhamid to the First World War), Kronik Kitap, Istanbul, 2018.

PAGE LAST UPDATED ON 30 DECEMBER 2023