The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the "Çanakkale Savaşı" (Battle of Çanakkale) in Turkey, holds a distinctive position among the battlefields where Turks engaged during the First World War. Its significance extends beyond the strategic importance of the Straits and the campaign's decisive nature; it unfolds as an epic drama, where the human facet of war takes precedence. Soldiers battled across hills and valleys amidst a relentless rain of fire, and the trench fighting in Gallipoli unfolded as a tragic narrative, with no man's land sometimes shrinking to just a few meters. Today, visitors to the Gallipoli peninsula find themselves captivated by its enchanting landscape, yet in 1915, this very peninsula was synonymous with death and suffering.

The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the "Çanakkale Savaşı" (Battle of Çanakkale) in Turkey, holds a distinctive position among the battlefields where Turks engaged during the First World War. Its significance extends beyond the strategic importance of the Straits and the campaign's decisive nature; it unfolds as an epic drama, where the human facet of war takes precedence. Soldiers battled across hills and valleys amidst a relentless rain of fire, and the trench fighting in Gallipoli unfolded as a tragic narrative, with no man's land sometimes shrinking to just a few meters. Today, visitors to the Gallipoli peninsula find themselves captivated by its enchanting landscape, yet in 1915, this very peninsula was synonymous with death and suffering.

For Turks, "Çanakkale" holds profound importance. It was the battleground where the Turkish army, facing a formidable multinational force backed by the era's mightiest navy, successfully thwarted the enemy, preventing an invasion of the Turkish homeland. The scale of the loss amplifies the campaign's significance, with Turks enduring approximately 250,000 casualties, including over 50,000 fatalities. The "Spirit of Çanakkale" has woven itself into the fabric of Turkish language, encapsulating a spiritual power that empowers individuals to "achieve the impossible."

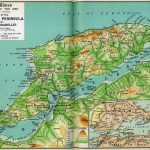

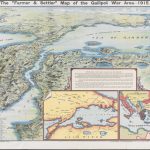

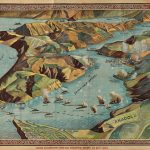

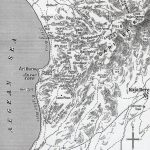

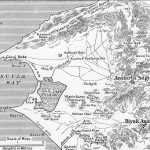

Stretching across 63 kilometers from the town of Gelibolu to Kumkale, the Dardanelles boasts a captivating landscape on both sides of its entrance at Seddülbahir. The straits, with a width fluctuating between 1,400 and 7,800 meters, have witnessed centuries of historical significance. This maritime gateway, framed by the Gallipoli peninsula, which extends a remarkable 90 kilometers, has played a pivotal role in shaping the course of events.

Notably, at Bolayır (Bulair), the peninsula narrows to a mere 5,500 meters, creating a confluence between the Aegean Sea and the Sea of Marmara. As one traverses southwards, the landmass gradually widens, reaching a breadth of 20 kilometers between Akbaş and Kemikli. However, the terrain is far from uniform; it undulates with hills, valleys, and ravines, adding a dynamic dimension to the historical canvas of this region.

Navigating through the twists and turns of history, the Dardanelles invites exploration, promising not only a visual feast of varied landscapes but a journey through the epochs that have shaped the destiny of nations. Whether contemplating the strategic importance of its narrowest points or immersing oneself in the natural undulations of its terrain, the Dardanelles stands as a testament to the interconnectedness of geography and history.

Preparing to Defend

At the onset of the European conflict and the Ottoman Empire's mobilization, the High Command diligently readied itself for an anticipated major Allied offensive in the Dardanelles, contingent upon Turkey's entry into the war. From the vantage point of the Ministry of War in Istanbul, the Allied nations harboured motives such as opening a supply route to Russia, severing the Turkish link between Asia and Europe, impeding the transfer of Turkish troops from Istanbul to other fronts, exerting pressure on the Ottoman government for a ceasefire, and compelling neutral Balkan states to align with the Entente.

On 2 August 1914, the Turkish General Staff's general mobilization directive reached the III Corps stationed in Tekirdağ, a town just north of the peninsula, and the command of the Çanakkale Fortified Zone. Both entities successfully concluded their mobilization efforts by 20 August. The III Corps, the resilient Turkish army corps unscathed from the Balkan Wars, was under the command of Maj. Gen. Esat Pasha and comprised the 7th, 8th, and 9th Divisions. Post-mobilization, its strength stood at 28,945 men and 7,402 animals.

The responsibility for defending the Dardanelles rested in the hands of the Çanakkale Fortified Zone command. Led by Brigadier General Cevat Pasha, this corps-sized unit comprised two infantry divisions: the 9th, under the command of Colonel Halil Sami Bey, and the 11th, commanded by Colonel Refet Bey. Alongside these infantry divisions, various artillery and supporting units formed an integral part of this defensive force.

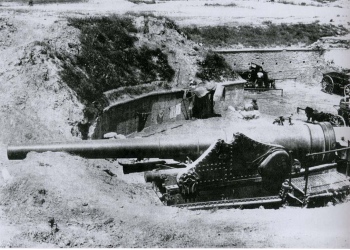

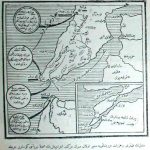

The fortifications securing the Dardanelles were organized into three layers: outer, intermediate, and inner defences. The outer defences centred on the historic forts at the straits' entrance - Kumkale and Seddülbahir. Armed with 13 heavy and 7 medium guns, albeit outdated, these forts set the initial line of defence. The intermediate defences safeguarded interior minefields and were armed with medium guns. Meanwhile, the inner defences boasted formidable strength, yet their aging guns and limited ammunition posed challenges.

To augment the coastal defences along the Dardanelles, forts were reinforced with artillery extracted from retired warships. A total of 230 artillery guns, including howitzers and mortars, were deployed. However, the majority, dating back 25-30 years, fell short in comparison to the cutting-edge artillery of the Allied fleet. Guns sourced from defensive lines near Istanbul (Çatalca and Edirne) and the Ministry of War depots also played a crucial role. Recognizing the need for expertise, the German General Staff dispatched Vice Admiral von Usedom, a coastal defence specialist, along with 500 German experts.

The passage of Goeben and Breslau on 10 August prompted the reinforcement of existing mine belts. Subsequently, the Dardanelles boasted 11 mine belts by the time of the major Allied offensive.

First Attack

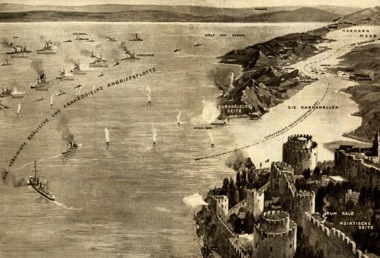

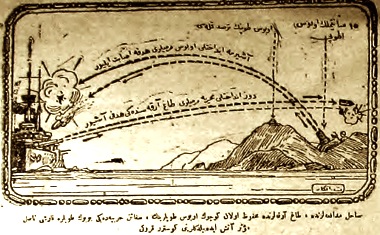

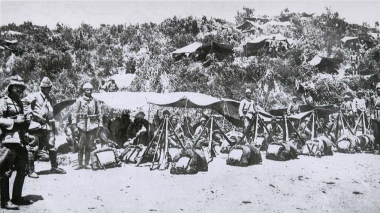

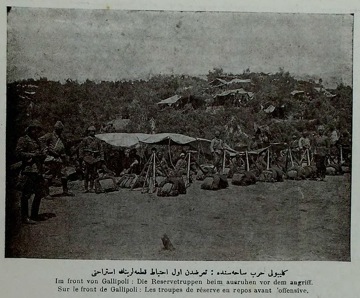

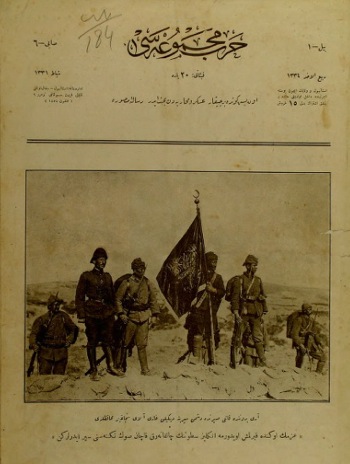

Reproduced from a German journal

On 3 November 1914, the Allied fleet issued its inaugural warning to the Turks. At 6:00 am, four warships emerged to the west of the straits, cruising at a swift 15 miles per hour. The British cruisers, Indefatigable and Indomitable, unleashed their artillery upon the Seddülbahir and Ertuğrul batteries on the European shore, while the French Suffren and Verité targeted the Kumkale and Orhaniye batteries on the Asian shore. A barrage echoed for 11 minutes from a distance of 12-13,000 meters. Turkish losses were unexpectedly high as a shell struck the ammunition depot at Seddülbahir. This event claimed the lives of 5 officers and 80 men, with an additional 20 sustaining injuries, marking the initial casualties for the Ottoman Empire in the First World War.

Despite achieving no military objectives, this assault underscored the vulnerability of the straits for the Turks. The following day, the III Corps headquarters relocated to Çanakkale, assuming defensive positions on both strait banks. Concurrently, the 9th Division joined the Command of the Çanakkale Fortified Zone. The 8th Division received orders for duty on the Sinai front, leading to the assignment of the new 19th Division, led by Lieutenant Colonel Mustafa Kemal Bey, to the III Corps. The 8th Artillery Regiment, commanded by the German Colonel Wehrle and equipped with 150 mm howitzers, was also deployed in lieu of the 8th Division.

On 13 December 1914, a pivotal moment unfolded in the chronicles of conflict as the British submarine B11, breaching Turkish waters, delivered a stern warning. Its torpedoes found their mark in the warship Mesudiye, anchored resolutely in the Bay of Sarısığlar. This event, a harbinger of change, prompted the installation of new submarine nets in the Dardanelles.

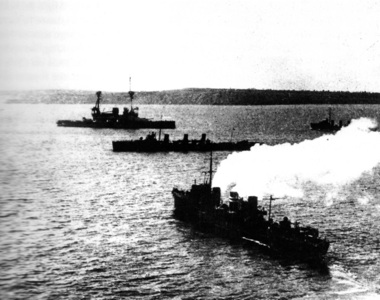

Since the inaugural assaults of 3 November, the Allied fleet, under the command of the British Vice Admiral Carden, steadfastly blockaded the Dardanelles. An armada comprising 49 British and 13 French vessels of diverse classes stood as a formidable maritime barrier.

The genesis of the Allied offensive to conquer the Dardanelles lied in the "Carden Plan," ratified on 15 January 1915 during a War Council meeting in London. This strategic blueprint outlined four primary objectives: firstly, the annihilation of the forts guarding the strait's entrance; secondly, the destruction of inner defenses from the strait's ingress to Kepez; thirdly, the hushing of batteries at the Narrows; and lastly, the eradication of mines, dismantling defensive positions at the Narrows, culminating in entry into the Sea of Marmara. This plan set the stage for a historical maritime endeavour that would shape the course of the conflict.

The Turkish defence strategy was based on four key elements, which proved to be pivotal during the unfolding events in the Dardanelles:

- On either side of the Dardanelles entrance, specifically Kumkale and Orhaniye on the Asian shore, and Seddülbahir and Ertuğrul on the European side, two batteries were strategically placed to thwart Allied warships attempting to navigate the Straits.

- Should enemy warships breach the Dardanelles, howitzers stationed in Erenköy and Tengerdere would unleash firepower, impeding their maneuverability within the Bay of Erenköy.

- To safeguard the mine belts and hinder enemy minesweepers, smaller batteries, equipped with guns repurposed from old warships and mortars, were strategically positioned. The Dardanos battery at Kepez and the Baykuş battery (later renamed Mesudiye due to the installation of salvaged guns from the warship of the same name) in Soğanlıdere played a crucial role. They either supported the howitzers in Erenköy and Tengerdere or provided fire support to the Çanakkale-Kilitbahir group.

- The central batteries situated in Çanakkale and Kilitbahir would initiate firing when enemy warships entered their designated range.

On 19 February, Admiral Carden undertook the initial phase of the Allied strategy. At precisely 9:51 am, six formidable Allied warships unleashed their firepower upon the forts guarding the entrance to the Dardanelles. The relentless barrage continued until 2:00 pm, unmet by any retaliatory gunfire. Positioned at a safe distance of 10-12 km, the Allied vessels remained beyond the reach of the Turkish artillery.

However, the situation shifted at 4:00 pm when Admiral Carden commanded the warships to draw nearer to the forts. As the Vengeance approached within 5 km of Seddülbahir, Turkish forces from Orhaniye and Ertuğrul initiated a counterattack. Faced with the realization that their assault was ineffective against the formidable Turkish forts, Admiral Carden reluctantly called off the operation at 6:00 pm. This endeavor to dismantle the forts guarding the entrance proved to be a discouraging setback for the Allied fleet.

In the face of relentless winds and adverse weather, the Allied fleet reluctantly delayed their renewed assault, a pivotal step in the execution of Carden's Plan. Finally, on 25 February, the Allied fleet stroke back. It began at 10:13 am when Queen Elizabeth, standing as a formidable force, opened fire upon Seddülbahir. Swiftly following her lead were Irresistible, Agamemnon, and Gaulois, bombarding the Orhaniye and Ertuğrul forts. In response, Turkish batteries fiercely retaliated, forcing Agamemnon and Gaulois to withdraw after sustaining significant damage. The relentless bombardment persisted until 5:30 pm, culminating in the silencing of the Turkish batteries guarding the entrance to the Dardanelles.

Simultaneously, Allied troops initiated landings at Kumkale and Seddülbahir ports. Despite facing a formidable counterattack, they managed to inflict damage by demolishing four cannons at Seddülbahir before their strategic withdrawal.

The onset of March 1915 witnessed a series of measured attacks by the Allied fleet. Almost daily, one or two warships penetrated the Dardanelles, subjecting Turkish coastal batteries to relentless shelling before tactically retreating. In contrast, attempts at mine sweeping by the Allied fleet faced staunch resistance, hindered by Turkish artillery fire.

Amidst these intense developments, Vice Admiral Carden succumbed to the accumulating strain and worry, prompting his departure from his post. On 16 March, the reins of command were assumed by Vice Admiral de Roebeck.

Turkish Victory of 18 March

18 March 1915 was a day with very fine weather and a calm sea in the Dardanelles.

“We were flying at an altitude of 1,600 meters. We counted 40 warships in front of Tenedos. We saw 19 dreadnoughts and heavy cruisers of which 15 were British and four were French. There were also three light cruisers and several cargo ships. Submarines could be hardly recognized… Six dreadnoughts were sailing towards the Straits… The French warship Bouvet opened fire on our airplane. We did not have time to lose and we returned to our base to give our report." (German Captain Serno and Captain Schneider who were flying above the peninsula for reconnaissance, 9am)

Upon receipt of the pilots' report, all Turkish units swiftly assumed their defensive positions. Command posts were abuzz with activity as binoculars fixated on the Dardanelles entrance. Turkish batteries, armed with 74 shore guns (eight salvaged from older warships), 82 mortars and howitzers, and 58 smaller cannons, stood poised to safeguard the Straits. Their adversary loomed, with a formidable array of 250 guns aimed at the Turkish soil from Allied warships.

The Allied fleet was coming in three groups. The first group consisted of De Roebeck’s flagship Queen Elizabeth, Agamemnon, Lord Nelson and Inflexible. The second group consisted of French ships: the flagship of the French Admiral Quepratte, Gaulois, as well as Charlemagne, Bouvet and Suffren. The third group was composed of older British warships: Prince George, Majestic, Vengeance, Irresistible, Albion, Ocean, Triumph, Swiftsure, Cornwallis, Canopus.

Allies warships commenced their journey at 10:05 am. A profound hush enveloped the Dardanelles as the expansive fleet inched forward. The tranquility shattered when, at 11:30 am, the Triumph unleashed its firepower on the Halileli hills, met with a swift artillery response from the Intepe battery. Four French ships joined the fray, elevating the tally of warships within the Dardanelles to ten, positioned along the Tengerdere-Halileli line.

The clock marked 11:40 am, initiating the onslaught as the first wave's four formidable warships bombarded Turkish forts. Queen Elizabeth's 38 cm cannons relentlessly targeted the Anadolu Hamidiye battery, while the Inflexible showered the Rumeli Mecidiye battery with a relentless rain of fire. The Turkish guns fell silent, unable to retaliate as the hostile ships lingered beyond their reach.

At 11:45 am, a shell launched from the Queen Elizabeth fell upon the town of Çanakkale, inducing widespread panic. Concurrently, Agamemnon and Lord Nelson fired a barrage upon the Rumeli Mecidiye battery, while the cruiser Weymouth bombarded Yenişehir. Triumph relentlessly pounded the Dardanos battery. Following an unabated 35-minute bombardment, Vice Admiral de Roebeck issued orders for the French group to forge ahead.

At 12:20 pm, the ammunition depot at the Çimenlik fortress endured a direct hit, inflicting severe damage. During these early hours, Turkish commanders grappled with the challenge of sustaining optimism amidst the unfolding situation.

"We saw that our strongest battery, the Hamidiye, was under heavy enemy fire and there were water columns and dust clouds appearing due to the direct hits received by the battery. I phoned the battery commander and he said that trenches are receiving direct hits and some guns are covered with earth, however they are now being cleaned and there is no serious damage. He also told me that they were going to open fire as soon as the enemy ships enter their range. This answer made me relax a little, however I know that the situation was going against us." (Lieutenant Colonel Selahattin Adil in his memoirs)

As the French warships drew nearer, breaching the effective range of Turkish guns, the dynamics of the confrontation underwent a profound shift. Turkish artillery, spearheaded by the Rumeli Mecidiye battery, unleashed a barrage that resonated across the waters, swiftly met by responsive fire from Dardanos and Mesudiye batteries.

The first warship to be hit was the Inflexible, succumbing to the relentless fusillade of Turkish-German artillery. The intensity of the bombardment wreaked havoc on the Allied fleet, with the Bouvet suffering substantial damage as it sought to approach Dardanos. Gaulois and Charlemagne, too, found themselves battered, while the Suffren endured a staggering 14 direct hits in a mere 15-minute span.

By 1:30 pm, the conflict had reached its zenith, each side unleashing its full firepower. Although the Allied fleet boasted a numerical advantage in active guns, the batteries on the European front – Mecidiye, Hamidiye, and Namazgah – bore the brunt of the relentless Allied assault. Communication lines faltered, with severed phone lines and the rupture of the cable linking Çanakkale and Kilitbahir. Meanwhile, Dardanos and Mesudiye batteries faced their own crucible under the weight of unrelenting fire.

Around 2:00 pm, Turkish artillery slowed down. Some guns sustained damage, and the forts received such severe pounding that firing at full capacity became impossible.

"Turkish and German artillery were sending their greetings to the enemy. They were breaking into their armored walls and annihilating their bodies. Above this scene, there was a wonderful oriental spring day with a blue sky and a shining sun. The air was shaken with the explosions at the forts. At around 2 o’clock in the afternoon the infernal noise subsided. Firing from the defences got weaker and the enemy thought that he is getting closer to his aims hoping that the forts are destroyed. The French fleet, which had been under heavy wire, was called back. It was replaced by a third fleet of six old British ships, which commenced fire." (A German officer, Carl Mühlman, in memoirs)

De Roebeck's plan held promise, yet a pivotal event ten days before the Allied attempt to breach the Dardanelles altered the campaign's fate. On the night of 7/8 March 1915, a small minelayer ship named Nusrat, under the command of Captain Hakkı Bey, sailed to Karanlık Harbour. There, Turkish mines previously cleared by De Roebeck's minesweepers were replaced by 26 new mines, strategically laid parallel to the shore.

On 8 March, Captain Nazmi Bey, the mine officer on Nusrat, wrote in his diary: “After receiving the orders, at 5:30 in the morning, Nusrat established a line of 26 carbonic mines starting from the Paleokastro point to the level of Erenköy and returned safely. The enemy did not see this operation. The distance between the mines is 100-150 meters and they are positioned at a depth of 4.5 meters.”

On 18 March 1915, at approximately 2:10 pm, Allied warships executed a crucial manoeuvre, veering starboard to facilitate the passage of minesweepers through the perilous mine belts en route to their base. It was at this juncture that calamity befell the Allied fleet. The beleaguered French warship Bouvet, having struck the unforeseen mines meticulously laid by Nusrat a mere ten days prior, succumbed to its fate, sinking within a mere three minutes.

The abrupt vanishing act of the Bouvet prompted a halt in the advance, as the French warship Suffren, along with compatriots Gaulois and Charlemagne, swiftly navigated towards the scene. Their mission was to rescue the survivors of the ill-fated Bouvet. However, the Gaulois, in the midst of this humanitarian effort, endured the cruel fate of receiving two direct hits, compelling a hasty withdrawal due to severe damage.

In the midst of this full-scale confrontation, both sides exchanged fire vigorously, while Allied minesweepers diligently worked to clear the waters of mines. The pivotal moment occurred at precisely 3:15 pm when the Irresistible succumbed to the impact of a mine. Shortly thereafter, at 4:10 pm, Inflexible also fell victim to an explosive encounter. The Inflexible bore the scars of an eight-meter-long and four-meter-wide breach, causing its engine room to rapidly fill with water, rendering the vessel immobilized.

Despite its dire condition, the Inflexible navigated out of the Straits. By approximately 5:45 pm, the beleaguered ship found itself grounded off the shores of Bozcaada (Tenedos). Simultaneously, the captain of the ailing Gaulois assessed the situation and determined that reaching Bozcaada was an unattainable goal. Evading the reach of Turkish artillery, Gaulois deliberately grounded itself at the Rabbit Island.

In the wake of these unforeseen setbacks, Vice Admiral de Roebeck, recognizing the futility of pressing forward, took a decisive step. At 5:50 pm, he officially called off the assault, issuing orders for minesweepers and warships alike to withdraw from the perilous waters of the Dardanelles and make their way back to their respective bases.

Another warship, Ocean, received orders to salvage the distressed Irresistible. Endeavoring to pull the beleaguered vessel from the challenging currents of the Straits, Ocean encountered insurmountable difficulties. As the clock struck 6:00 pm, Ocean reluctantly departed from Irresistible, only to encounter further adversity within a mere five minutes – striking yet another mine strategically laid by Nusrat. The crew, amidst intense Turkish gunfire, faced the daunting task of evacuating the vessel. The destinies of both Ocean and Irresistible were sealed that day, as they floated momentarily before succumbing to the depths.

Remarkably, on that fateful day of 18 March 19155, Turkish batteries unleashed a formidable barrage, discharging a staggering total of 1,935 rounds. The resounding echoes of long-range shore guns at Hamidiye, Mecidiye, and Namazgah batteries, alongside the unwavering performance of the long-range medium-sized guns at Baykuş and Dardanos batteries, left an indelible mark. These batteries, resilient even under severe hits, played a pivotal role in securing a decisive victory, as they steadfastly continued their relentless fire.

Total casualties of the day were 118 men for Turks. Four officers and 40 men were killed in action, 74 men were wounded. Meanwhile, the German contingent reported three casualties in the form of lives lost and 15 soldiers wounded. The narrative takes a somber turn when we delve into the Turkish perspective, particularly at the ill-fated Dardanos battery. Though the battery suffered just one direct hit, the blow struck the heart of a small field hospital, claiming the lives of Commander Captain Hasan Bey, his surveillance officer Lieutenant Mevsuf Efendi, and nine enlisted personnel. In the aftermath, this unit bore a solemn transformation, christened as the "Hasan-Mevsuf Battery."

Beyond the human toll, the Turks saw the loss of nine cannons, with most forts bearing the scars of heavy bombardment. The town of Çanakkale and the village of Kilitbahir were not spared either, witnessing fires and structural damage. Çanakkale, in particular, saw the collapse of 35-40 houses, leaving numerous civilians injured and homes in ruin.

The Allied forces faced far more significant losses during this engagement. Three warships were lost, and an additional four were rendered out of service, resulting in around 800 human casualties. Among these losses, the sinking of Bouvet left the Allies in profound shock.

This marked the culmination of the Allied fleet's final attempt to break through the Dardanelles. Recognizing the inadequacy of naval strength alone, Allied commanders made the strategic decision that naval forces alone could not secure victory in the Dardanelles campaign.

In the meantime, the Turks were bracing for a potential renewed naval assault. Despite their readiness, the situation appeared unfavorable from their perspective. Their remaining ammunition was sufficient for only an additional two days of sustained fighting. Crucially, three artillery guns were completely devoid of shells, and others possessed a mere 18-50 shells. While eight mine belts remained intact, there were no replacements available. Turkish soldiers diligently worked to repair damaged fortifications to the best of their ability.

The looming question lingered: What if the Allied fleet launched another attack the following day? The outcome remained uncertain, but the defenders of the Dardanelles harboured genuine concerns as the tides of war continued to ebb and flow.

"We could not sleep because of the anxiety of 19 March. With the first lights of the day our binoculars began to scan the horizon. Neither on 19 March, nor on the following days could we see any ships except the regular patrol boats. Everyone was relieved." (Carl Mühlman in his memoirs)

In the evening of 18 March 18, as the sun was going down and the last few of the warships disappeared on the horizon, Turkish commanders were on a hill observing the retreat of this mighty fleet.

"They are gone. They could not break through. They will not break through." (Cevat Pasha, commander of the Çanakkale Fortified Zone)

First Day on the Peninsula

First Day on the Peninsula

Enver Pasha had previously outlined a defensive strategy for the Turkish straits, Bosphorus and Dardanelles, on 20 February. According to the plan, the First Army was tasked with defending the European sides of both straits, while the Second Army assumed responsibility for the Asian sides. This arrangement, assigning both armies roles in both straits, contradicted the unity in command principle. General Otto Liman von Sanders, the First Army's commander, raised objections, leading to a revision of the plan after the events of 18 March.

Subsequently, a new army headquarters, the Fifth, emerged, encompassing the III and XV Corps, along with the 5th Division and a cavalry brigade. This formidable force, totaling 80,935 men, increased the defenders in this theatre to 93,512, including the Çanakkale Fortified Zone Command. On 25 March, General von Sanders assumed command of this newly established army.

General von Sanders, recognizing the vast expanse of the peninsula and the adjacent Asian shores, deemed it impractical to establish a defensive barrier along the extensive coastlines. Diverging from Turkish commanders, particularly Esat Pasha, who advocated for coastal defense, von Sanders asserted the necessity of an inland defense strategy. The Fifth Army, under his command, strategically positioned a light infantry screen in outposts strategically placed on elevated terrain overlooking potential landing sites.

These outposts, typically organized in platoon strength, were fortified with wire and meticulously prepared trenches. Contrary to the notion of halting the enemy at the beaches, the Turks, led by von Sanders, envisioned a different approach. Regiment-sized forces were strategically stationed three to five kilometres behind the coastlines, positioned within sheltered terrain. The intent was not to confront the Allies directly on the beaches with these troops but to employ them in a counterattack role.

By slowing the enemy's landing through the outpost deployment, the Turks aimed to channel the invaders' advance. The larger forces positioned inland would then launch counterattacks against the encroaching enemy. The hope lay in the swift execution of these counterattacks, either immediately or as promptly as possible, with the objective of repelling the unsuspecting invaders back to the sea. The Turkish commanders, at all echelons, meticulously rehearsed these counterattacks, ensuring preparedness for any eventuality. The Fifth Army stood poised, ready to confront and repel the impending enemy invasion.

In assessing potential landing sites, Gen. von Sanders diverged from the III Corps report, identifying three particularly perilous areas: Beşike Bay on the Asian side, Bolayır in the north, and the southern tip of the peninsula. Plans were crafted as follows:

- The Fifth Army Headquarters and ancillary units: Located in the town of Gelibolu. The independent cavalry brigade responsible for the stretch west of Bolayır to Enez at the mouth of the Maritsa River.

- III Corps: Commanded by Esat Pasha. Headquarters located in the town of Gelibolu. Responsible for the defence of the peninsula. 7th Division (19., 20., 21. Regiments and an artillery regiment to defend the area north of Bolayır. 9th Division (25., 26., 27. Regiments and an artillery regiment) and two gendarmerie battalions to stay in the peninsula itself. 19th Division (57., 72., 77. Regiments and an artillery regiment) to remain in reserve at Bigalı.

- XV Corps: Commanded by Colonel Weber. Headquarters located at the Calvert Farm on the Asian side. Responsible for the defence of the Asian side with the 3rd Division (31., 32., 39., 64. Regiments and an artillery regiment), 11th Division (33., 126., 127. Regiments and an artillery regiment) and a gendarmerie regiment.

- 5th Division: To remain in reserve north of the peninsula. Composed of 13., 14. and 15. Regiments and an artillery regiment.

As Turkish troops awaited the anticipated enemy landing, the Allies prepared for the invasion. Following the naval attack failure, ground troops became imperative. The British Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, led by General Ian Hamilton, assumed the task. The Australian and New Zealand volunteer soldiers, now the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), along with the British 29th Division, the Royal Naval Division, and the French Corps Expéditionnaire d'Orient, formed Gen. Hamilton's command.

Prepared to confront the invaders, the Turkish forces assumed their positions, armed with inadequate equipment but fueled by high spirits. The only remaining task was to await the commencement of Allied amphibious operations. This vigil ended in the early hours of 25 April 1915 when the Allied forces landed at six different locations on the peninsula and at Kumkale on the Asian shore.

Landings Begin

The Allied ships that had left the port of Mudros the day before met at the assembly point, 9 km from the landing beaches, at 1:30 am on April 25. From there, a force of 1,500 soldiers, the Anzacs, sailed towards the peninsula. Faik Efendi, a company commander with the Turkish 27. Regiment, was looking through his binoculars. He could see the ships coming: “As the moon descended, darkness shrouded the ships from view. The reserves were alarmed and they were ready for action. I was waiting for the outcome and watching the distance. Soon we heard the roaring of the guns.”

The Arıburnu landing area, designated as Z Beach, spanned a wide 6 km stretch from 1.5 km north of Kabatepe to Fisherman's Hut near Anzac Cove. The Australian 3rd Brigade's two companies were the first to land, commencing their beachhead establishment just before dawn at 4:30 am on 25 April. Originally intended a mile north of Kabatepe, the landing veered 2 km northward, settling in a shallow cove between Arıburnu and Küçük Arıburnu (Hell Spit).

The Anzacs found themselves amidst a perplexing network of ravines and spurs descending from the heights of the Sarıbayır range to the sea. Defended by 80 Turkish soldiers, their ranks soon swelled with reinforcements, though still at odds, outnumbered one to ten. Despite their efforts to halt the invaders, the Anzacs persisted, aided by naval gunfire, successfully securing a 1.8 km beachhead. By 5:30 am, the shores hosted 4,000 troops. Halil Sami Bey, Commander of the Turkish 9th Division, swiftly issued orders: "The British are landing at Arıburnu and Kabatepe. The 27th Regiment, along with the mountain battery at Çamburnu, will advance towards Kabatepe to repel the enemy to the sea."

The clash on the beach concluded at 6:00 am as the Haintepe (Plugge's Plateau)-Yükseksırt (Russell's Top) defensive line succumbed to the Anzacs. At that juncture, the Turkish forces engaged in the battle numbered no more than 600, a figure already halved by then. Of the 80 soldiers from the 8th Company of the 27th Regiment, who initially confronted the enemy, only three survived.

The Anzacs, though advancing on the ridges, faced unexpected hindrances in their progress. The Turkish resistance proved more robust than anticipated, compounded by the fact that the Anzacs landed 2 km north of their intended location. Simultaneously, the 27th Regiment moved to support the Turks. By 7:00 am, two battalions comprising 2,000 men and a machine gun detachment arrived in Kavaktepe. Regiment commander Lt.Col. Mehmet Şefik Bey observed the Australians seizing Kanlısırt (400 Plateau), possessing a strategically superior position. In his memoirs, he noted, "Enemy soldiers were clearly visible at Kanlısırt and other ridges to the north. From the sounds of gunfire and the movements one could tell that some fighting was going on there. To the east, the terrain was more rugged and covered with bushes. Nothing much could be seen there. It was difficult to tell where the flanks and the advance units of the enemy were." Şefik Bey initiated a counterattack at 8:00 am, successfully repelling the enemy to Edirnesırtı (Mortar Ridge)-Kanlısırt Plateau.

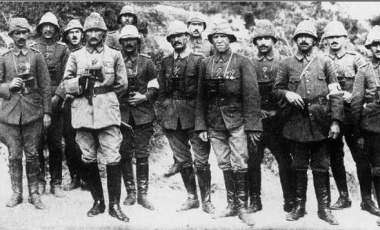

Although the Anzacs were momentarily halted and the Turks held their ground, the precariousness of the situation loomed large. The enemy's total strength had swelled to 10,000, and a subsequent assault was imminent. In response, Commander of the 9th Division, Colonel Halil Sami Bey, instructed the 19th Division, led by Lieutenant Colonel Mustafa Kemal Bey, to relocate to Kocaçimen. Their objective: encircle the enemy from the north and reinforce the 27th Regiment.

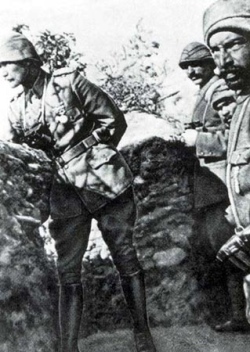

Australians advanced towards the commanding heights of the narrows, Kocaçimen, and Conkbayırı (Chunuk Bair). Mustafa Kemal Bey, reaching Conkbayırı at 9:40 am and establishing his headquarters at Kemal Yeri (Scrubby Knoll), made a pivotal decision that sealed the fate of the Anzac landing. Without awaiting orders, he personally led the entire 57th Regiment forward for a counter-attack, notifying the corps headquarters: "The strength of the enemy, evident between Kabatepe and Arıburnu, remains unclear. To prevent the enemy from seizing the ridges west of Kocadere, I'm directing the 57th Regiment and a mountain battery in that direction. Leaving the Chief of Staff at headquarters, I move to the zone to assess the enemy's position and take necessary measures. I'll resume command when a larger part of the division is required." The 19th Division's remaining regiments, the 72nd and 77th, would join the fray in the evening.

At 10:24 am, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Hüseyin Avni Bey, the 57th Regiment launched an attack against the enemy. It was during this critical moment that Mustafa Kemal issued his memorable order: “I do not order you to attack; I order you to die! In the time until our demise, other troops and commanders can assume our position.” They valiantly defended the right flank of the Turkish defence. The 1st Battalion of the 57th Regiment advanced along Edirnesırtı towards Kılıçbayırı (Baby 700) from the inland side, while the 2nd Battalion circled behind Düztepe (Battleship Hill) and progressed down the range on the seaward side of Kılıçbayırı.

On that fateful day, the 27th Regiment clashed with the Australians on the left flank, forcing the Anzacs into repeated withdrawals. Their resilience endured until 4:00 pm, when the 57th Regiment launched a significant counterattack on Kılıçbayırı. Simultaneously, the 27th Regiment pressed forward on Kanlısırt-Merkeztepe-Kırmızısırt (Johnston's Jolly). Artillery support bolstered their assault, breaching the Anzac line and compelling them to relinquish the hill. Survivors retreated to the southern slopes of Kanlısırt, and the battle persisted until dusk. Thanks to precise artillery fire, the Turks maintained control over the Anzacs at their beachhead, securing dominance over the hills.

The weakest link of the Turkish line on 25 April was the 77. Regiment. Following the 27th Regiment onto the battlefield, it executed a bayonet charge against the Anzacs. Yet, when met with enemy fire, the regiment disintegrated, plunging into panic. In a tragic turn, some soldiers fired indiscriminately, inadvertently taking the lives of comrades from the 27th Regiment. That night, Lieutenant Colonel Saip Bey, the commander of the 77th Regiment, apprised Mustafa Kemal Bey of the situation. Mustafa Kemal Bey, discerning the true cause, refuted the blame on the soldiers, citing Saip Bey's misguided orders based on unreliable information. Despite the setback of the 77th Regiment, the 19th Division's operational plans were thwarted, and the opportunity for a decisive blow against the retreating enemy slipped away.

Seddülbahir Landings

In the northern reaches of the peninsula, the Turks valiantly defended their homeland against the advancing Australians and New Zealanders. Meanwhile, British forces orchestrated landings at five distinct points in the southern expanse. Notably, the Seddülbahir sector (Cape Helles) witnessed the arrival of the British 29th Division, commanded by General Aylmer Hunter-Weston. The commencement of landings followed 1.5 hours of naval bombardment, initiating at 4:30 am on 25 April.

Major Mahmut Sabri Bey, commander of the 3rd Battalion of the 26th Regiment, provided a firsthand account:

"Warships approached our shores between Teke Bay and Eski Hisarlık, relentlessly unleashing their firepower. The ridges at Seddülbahir erupted with countless explosions, obscuring our frontline trenches with black, white, and green smoke clouds caused by the blasts. Discerning the units present and assessing the damage became impossible. The 3.7 cm light artillery under our battalion's command fell victim to the shelling, losing two guns. Regrettably, this battery, crucial for beach battles, lay unusable. The formidable naval onslaught decimated our trenches at Teke Bay and Ertuğrul Bay. Communication trenches, partially constructed, were obliterated, and obstacles established by our frontline units suffered extensive damage." (Major Mahmut Sabri Bey in his memoirs)

The historic landing at Pınariçi Bay, known as Y Beach, unfolded in synchrony with the commencement of naval gunfire. Caught unawares, the Turks, their attention fixated on Ertuğrul and Teke Bays (V Beach and W Beach), were ill-prepared for landings at this bay. Without encountering resistance, a British brigade swiftly secured a beachhead, ascending a narrow gully leading to Sarıtepe (Gurkha Bluff) and advancing to the village of Kirte (Krithia - modern-day Alçıtepe). At 9:30 am, news of this unexpected landing reached the headquarters of the 26th Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Hafız Kadri Bey.

Minor Turkish units engaged the British around Sarıtepe, and in the afternoon, a battalion, a field battery, and two machine guns from the 25th Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel İrfan Bey, reinforced the Turkish defence. The conflict persisted until the early hours of the next day, resulting in heavy casualties for both sides. The British forces withdrew from Pınariçi Bay at 11 am the following morning. The Turkish side had a delayed realization of the enemy's operation in this area, but the British failed to exploit this vulnerability.

Another landing beach aimed at supporting the main landings at Ertuğrul and Teke Bays was İkiz Bay (X Beach), situated 2 km northwest of the village of Seddülbahir. Weakly defended by the Turks, who suffered considerably from naval gunfire, around 1,000 British troops established a beachhead by 7:30 am, moving inland. Two small Turkish groups, each consisting of around 40 troops, arrived from Zığındere and Teke Bay, opening fire on the British. A company from Kirte soon reinforced the Turkish defence.

Despite being vastly outnumbered, the Turks succeeded in impeding the enemy's progress towards the ridge overlooking Teke Bay. The decision by the 9th Division headquarters to deploy reserves to this area proved judicious. As the sun set on 25 April, approximately 3,000 British troops had landed at İkiz Bay, capturing Karacaoğlan Hill (Hill 114). However, they were unable to breach the Turkish defence, remaining confined to their beachhead. The Turks thwarted their advance towards Ertuğrul Bay and Kirte.

The landing at Morto Bay, situated on the southern expanse of the peninsula, unfolded along the shores adjacent to Eski Hisarlık Burnu, known as S Beach. This coastal stretch bore witness to the valiant defence mounted by a Turkish squad. The moment the boats reached the shore, a torrent of gunfire erupted from the Turkish defenders, exacting a heavy toll on the British forces. Swiftly discerning the British maneuvers to encircle them, the Turkish commander, displaying tactical acumen, ordered a strategic withdrawal. This judicious decision led the Turkish troops back to the protective ridges, averting a potential threat to the vital Seddülbahir-Kirte supply line. Timely reinforcements arrived, confining the British contingent to the dilapidated environs of Eski Hisarlık, notably De Tott's Battery.

On the first day of the land battles in Gallipoli, 25 April, two major landings took place at the Seddülbahir sector. One of them took part at Teke Bay (W Beach) which was one of the coastal points where the Turkish defence was the strongest. Here, the Turkish defense stood resolute, anchored by a company from the 3rd Battalion of the 26th Regiment—approximately 240 steadfast men. Against overwhelming odds, more than 1,000 British troops commenced their landing at 6:15 am, marking a momentous chapter in the unfolding drama of Gallipoli's historic saga.

Turks were positioned at the northern side of the ba, observing the approaching invaders. As the boats made landfall, all hell broke loose. Fierce Turkish gunfire, coupled with intricate barbed wire obstacles, inflicted significant harm upon the British forces. To compound their challenges, the inadequacy of their wire cutters became apparent, exacting a heavy toll as they grappled with the robust Turkish barriers.

The Turkish defensive strategy proved formidable, yet their numerical strength fell short. At 7:30 am, a pivotal moment unfolded as British forces successfully secured a beachhead. The conquest of Karacaoğlan Hill followed at 11:00 am, while the capture of Aytepe (Hill 138) marked the evening's triumph. Despite sustaining substantial casualties, the tenacious Turkish defenders refused to yield. Determined to hold their ground, they persisted in the relentless struggle, ultimately thwarting the British advance by day's end.

The largest contingent of British troops landed at Ertuğrul Bay (V Beach), near the village of Seddülbahir, a short distance to the east on the opposite side of Teke Bay. A force of 6,000 men was earmarked for this strategic landing site. At 6:00 am, the initial wave of 3,000 soldiers commenced their arrival, following a relentless bombardment of Turkish positions by Allied naval gunfire.

A covering force of approximately 2,000 men disembarked from the converted collier, River Clyde, deliberately grounded beneath the formidable Seddülbahir Fort. This tactical maneuver allowed troops to exit directly via ramps to the shore. An Irish battalion chose open boats for their landing. The area was fiercely defended by a company from the 3rd Battalion of the 26th Regiment. Positioned on heights overlooking the bay and within the fort, they promptly opened fire.

The consequence was a swift and brutal encounter, with Turkish gunfire exacting a toll on the men in the boats. A handful managed to reach the shore, seeking refuge under a sand bank at the beach's edge, where they remained pinned down. The fate of those inside the River Clyde mirrored the struggle. Troops, emerging individually from the sally ports on the collier, provided ideal targets for Turkish gunfire. Only 200 men successfully made it onto the beach, underscoring the intensity and challenges of this landing.

Landing at Ertuğrul Bay was completed by 9:30 am. Later in the day, the British endeavored to seize control of Gözcübaba Hill (Hill 159), which commands a view over the bay. Against this advance, a small group under the leadership of Sergeant Yahya, hailing from the 10th Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 26th Regiment, valiantly safeguarded the hill, repelling the enemy with a resolute bayonet charge. Meanwhile, the 1,000 remaining men aboard the River Clyde awaited the cover of night before embarking on another landing attempt.

It is essential to highlight that, contrary to most British accounts, the Turkish defenders, during the initial landings, lacked access to machine guns. Both at Arıburnu and Seddülbahir, the Turks responded to the invasion forces with infantry rifles. It was not until the night of 26 April that the defensive lines at the beaches saw the introduction of the first machine guns.

Diversions at Bolayır and Kumkale

The main objective of the first day for the allies was the attainment of the Kilitbahir Plateau, yet this objective remained elusive. Concurrently, as Arıburnu and Seddülbahir witnessed landings, two additional operations unfolded with the intent to divert Turkish attention and manpower. In the Gulf of Saros, to the north of the peninsula, a strategic diversion unfolded. General Liman von Sanders anticipated Allied landings, leading to the bombardment of Bolayır. Alongside, a British officer swam ashore, igniting flares to distract the defending Turkish forces successfully. This diversionary tactic led to the containment of Turkish 5th and 7th Divisions, totaling 20,000 men, while the main landings encountered only a handful of defenders.

It was by late afternoon on 25 April 25 when General von Sanders was convinced that the Allied presence at Bolayır was a diversion. Responding to Esat Pasha's calls for reinforcements, Turkish forces could only reach the actual war zones the next evening.

Simultaneously, another diversion unfolded at the Asian shore, defended by the Turkish XV Corps. The Allies sought to impede the movement of Turkish troops to the peninsula and neutralize Turkish guns targeting landing units. Following a 3.5-hour naval bombardment starting at 5:00 am, French units landed at Kumkale, an area under the oversight of the 31st Regiment led by Lieutenant Colonel İsmail Hakkı Bey.

Informed promptly about the French landing, the Turkish headquarters, despite being outnumbered, skillfully halted the advance of approximately 3,000 troops at Kumkale. The defenders received reinforcement from the 39th Regiment under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Nurettin Bey in the afternoon. As the day waned, the Turks initiated three night attacks in an attempt to push the enemy back to the sea, but these efforts failed, leading to a stalemate.

The Turks soon realised that it was only a diversion at Kumkale. Captain Celaleddin Bey reflected in his memoirs: "By the afternoon of 25 April, the situation became clear. The actual landings occurred on the European side. It was evident that the forces at Kumkale amounted to no more than one to three battalions." Despite maintaining their beachhead for an additional day, the French evacuated the Asian shore on the night of 26 April, having achieved their goal of preventing Turkish 3rd and 11th Divisions from reinforcing the peninsula's defense.

On 25 April 1915, a total of 16,700 Turkish troops defended against an invasion force of 31,750, resulting in 6,000 Turkish casualties and 5,000 for the Allies. At Seddülbahir, 4,700 Turks faced 14,000 Allied troops, with casualties numbering 1,700 and 2,200, respectively. Meanwhile, at Arıburnu, 8,500 Turks confronted 14,500 Allied troops, resulting in casualties of 2,500 for the Turks and 2,000 for the Allies. Kumkale witnessed the highest Turkish casualty rate, with 3,500 troops in action and 1,735 casualties, while the French experienced a casualty rate of 778 out of 3,250.

Trenches of Arıburnu

In the morning of April 26, 1915, the total Turkish strength at the northern part of the peninsula, the Arıburnu sector, witnessed a Turkish force numbering approximately 10 thousand strong, backed by 16 machine guns and 28 artillery pieces. Despite facing a formidable Anzac contingent of 20 thousand soldiers, the Turks started the day at a considerable disadvantage due to the departure of the 77th Regiment from its position at Kanlısırt (400 Plateau). Fortuitously, the Anzacs, rather than capitalizing on this vulnerability, had spent the night engaged in digging trenches.

In response to this unfolding situation, Mustafa Kemal swiftly directed two battalions of the 72nd Regiment to the left wing, aiming to bridge the resulting gap. The Anzac offensive kicked off in the early hours, targeting the Turkish right wing and receiving support from intense naval gunfire concentrated on Kabaksırtı, also known as Sniper’s Nest. While the Turks successfully repelled this assault, the Anzacs, through a renewed effort, managed to seize Kılıçbayırı, commonly referred to as Baby 700.

As the day progressed, the Anzacs exerted pressure on the left wing at Kanlısırt, only to face a resilient response from the 27th Regiment, resulting in their eventual retreat.

Mustafa Kemal meticulously planned a large-scale counterattack, executing it at 7:30 am on 27 April. Turkish forces, strategically positioned at the centre and left wing, swiftly pressed forward. Within an hour, units from the 27th, 72nd, and 77th Regiments compelled the adversary to retreat, relinquishing ground to the seaward side of Kanlısırt-Kırmızısırt Plateau.

Meanwhile, reinforcements streamed in. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Ahmet Şevki Bey, the 33rd Regiment fortified the Kanlısırt-Kırmızısırt (Johnston's Jolly) line, while Major Servet Bey's 64th Regiment partnered with the 57th Regiment for an attack from the right wing. The ensuing clashes in this sector endured throughout the day, with pivotal positions frequently changing hands. Ultimately, the Anzacs were forced to retreat to the south side of Cesarettepe (The Nek) and Bombasırtı (Hill 60).

Following an unsuccessful Turkish night attack on 27/28 April, positions in this sector nearly stabilized. In the subsequent days, an influx of Turkish reinforcements continued. Regiments from the 5th and 11th Divisions were deployed to this sector, while the Asian side of the Dardanelles, having already stabilized, saw the arrival of units from the 3rd Division. Turkish commanders, resolute in delivering a decisive blow to the enemy, scheduled a major offensive for 1 May.

At Arıburnu, Turkish forces, numbering 15,500 strong and backed by six mountain batteries and two field batteries boasting a total of 34 guns, along with 28 machine guns, faced off against Anzac troops strategically positioned with 24 battalions and over 100 machine guns at key vantage points. Mustafa Kemal devised a plan to launch an assault from the centre towards Merkeztepe (MacLaurin’s Hill.)

At 5:00 am on May 1, 1915, Turkish guns began to shell the expanse between the ridges of Yükseksırt (Russell’s Top) and Kanlısırt. The 14th Regiment spearheaded the attack, closing in on the Anzac trenches with a proximity of 200 meters. By 10:30 am, the 125th Regiment joined the offensive, but the flanks struggled to reinforce the centre. Despite well-dug Anzac defenses, Turkish attempts to breach their lines proved futile. A subsequent night assault met a similar fate. The Turks found themselves unable to advance, but neither could they retreat. By day's end, Turkish casualties numbered no less than 6,000.

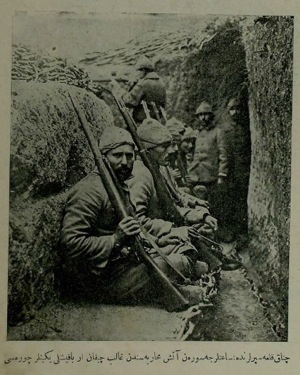

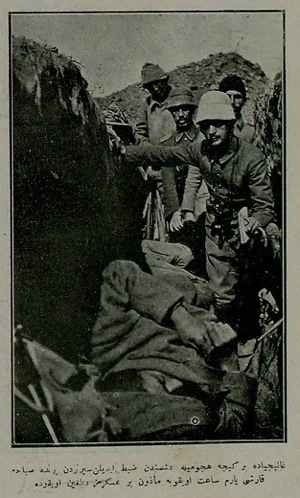

Eight Meters Between the Trenches

After the unsuccessful attempt, the Turks commenced digging trenches, mirroring the strategy adopted by the Anzacs. In certain sectors, Turkish and Anzac trenches lay in close proximity. This geographical proximity intensified the confrontations as both forces ventured dangerously near each other's lines. Over the subsequent fortnight, a series of night assaults unfolded, with Bombasırtı (Quinn’s Post), Korkuderesi (Monash Valley), and Kanlısırt witnessing particularly heightened activity. Noteworthy among these encounters were the Anzac night attacks on 9/10 May and 13/14 May, showcasing remarkable displays of human resilience and determination.

"The distance between the trenches is eight meters, which means that death is inevitable. Those in the first trenches, they all fall without any survivors, but they are rapidly replaced by those in the second. Can you imagine what a distinguished determination and faith this is? He sees the fallen, he knows that he will die within three minutes, but he does not hesitate at all. There is no trembling whatsoever. Those who are literate have the Koran in their hands, preparing to get into heaven; those who are not are saying prayers. This is an example showing the spiritual power of the Turkish soldier. You can be sure that this spirit is what brought the victory in Çanakkale." (Mustafa Kemal in his memoirs)

On 5 May 1915, General von Sanders endeavored to unite the diverse formations on the peninsula into cohesive combat groups, establishing a corps-level group headquarters. The Northern Group, consolidating all Turkish forces at Arıburnu and Anafartalar, was placed under the command of Esat Pasha, the commander of III Corps. This group comprised three divisions: Mustafa Kemal’s 19th Division on the right, Lieutenant Colonel Hasan Sabri’s 5th Division in the centre, and Colonel Rüştü’s 16th Division on the left.

As trenches were dug at Arıburnu, the southern part of the peninsula experienced an escalation in the battle. Following the substantial losses on the landing day, British forces swiftly recovered. In the early hours of the next day, units at Ertuğrul Bay (V Beach) advanced towards the village of Seddülbahir. Despite the valiant defense by the 3rd Battalion of the 26th Regiment, as seen on the landing day, they were vastly outnumbered and running out of ammunition.

Major Mahmut Sabri Bey ordered a retreat, and by 1:30 pm, the village and the coastal stretch were in British hands. The Turks withdrew disorganized, luckily avoiding pursuit by British forces who occupied Harapkale Hill and commenced trench digging.

Fearing a robust Allied advance, Colonel Halil Sami Bey, commander of the 9th Division, proposed establishing a second defensive line further north, reaching the village of Kirte (Krithia - modern-day Alçıtepe). Headquarters rejected this proposal, which risked surrendering Kirte, Zığındere (Gully Ravine), and Kerevizdere to the enemy. Instead, a new defensive line was to be formed to the front, ensuring Kirte remained within Turkish territory. The 20th Regiment held the right wing, the 19th Regiment the left, with the 25th and 26th Regiments in reserve. This defensive formation boasted nearly 8,000 men, supported by three field batteries and three howitzer batteries, totaling 24 guns.

The primary objective of the British was seizing the village of Kirte. Despite three days of reinforcing their beachhead and enduring severe casualties, particularly on the landing day, they planned a significant breakthrough attempt. Their combined strength, including French forces transferred across the Narrows, approached 17,500 soldiers.

The offensive by the Allies, now famously referred to as the First Battle of Kirte, commenced with a barrage of heavy artillery in the early hours of 28 April 1915. At 9:00 am, Allied forces embarked on their northward advance. Units assaulting the right wing of the Turkish defence approached Pınariçi Bay (Y Beach) but encountered staunch resistance from the 20th Regiment's intense fire. Conversely, the situation on the centre and left wings proved unfavourable for the Turks. The 25th and 26th Regiments failed to maintain their lines, prompting a withdrawal. Simultaneously, the pivotal 19th Regiment lagged behind, hindered by Allied naval gunfire. Despite Colonel Halil Sami Bey's order for a retreat, regiment commanders, seeing the enemy's advance slowing, defied the directive. Major Mahmut Sabri and his battalion spearheaded a successful counterattack, echoed by the 20th Regiment on the right wing. The Allies were forced back to their starting points, dealing a final blow with the arrival of the 19th Regiment. By day's end, the Allies had made no gains and suffered nearly 3,000 casualties, while Turkish losses numbered 2,378 men.

Recognizing the need for sector reorganization, General von Sanders established the Southern Region Command under the leadership of German Colonel von Sodenstern. Sanders also secured reinforcements, and the Turkish General Staff deployed the 15th Division to the front. With Halil Sami's 9th Division on the right flank and Colonel Remzi Bey commanding the 7th Division on the left, this area command was ready for action.

At 3:30 pm on 1 May, Colonel von Sodenstern issued a directive for a night attack on Allied lines, scheduled to commence at 10:00 pm the same day. The brief preparation time left units scrambling. During the attack, the 20th Regiment, led by Major Halit Bey, faced British machine gun fire on the right wing, resulting in repulsion. Meanwhile, on the left, Colonel Halil's 21st Regiment, the 19th Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Sabri Bey, and the Bursa Gendarmerie Battalion commanded by Major Tahsin Bey engaged in fierce fighting and bayonet charges against the British. Despite their valiant efforts, these attacks failed, and the Turks, suffering severe casualties, retreated to their initial lines. One night of conflict cost the Turks 6,000 men, while Allied casualties reached 3,000.

On the night of 3 May, a renewed offensive, supported by the recently arrived 15th Division from Istanbul, met with resounding failure. The Turkish units plunged into utter disorder and chaos, and the 15th Division, unacquainted with the terrain, suffered a staggering loss of half its men in a single night. The toll on Turkish casualties at the Seddülbahir sector soared to 10,000 within a week.

Following these catastrophic events, the Southern Group Command was established he next day, with German General Weber, commander of the XV Corps, at its helm. The Turkish forces in this sector dwindled to a mere 13,000 men, backed by 57 pieces of artillery and 24 machine guns.

During the ill-fated night assaults in the early days of May 1915, a considerable number of Turkish soldiers met their demise. The Allies were not the primary cause; rather, the tragic loss of lives can be attributed mainly to misguided decisions and practices. On the evening of 3 May, the 15th Division, arriving as reinforcements, marched a challenging 25 kilometers to reach the battlefield. Exhausted soldiers were dispatched to the frontline in smaller units. The situation was marred by ambiguity – the division's responsibility zone, the intended direction of advancement, and the specifics of its engagement remained unclear. There existed no written orders; information was disseminated solely through word of mouth to the divisional commander and the battalions.

“Our initial task was to secure our defense by fortifying our positions until reinforcements could be mobilized, preparing for subsequent offensives. However, the Army Command adhered stubbornly to their own perspective. Upon the arrival of fresh units, they promptly deployed them to the frontline, initiating a series of consecutive night attacks. This misguided approach resulted in the loss of several seasoned and well-trained army units, along with the tragic sacrifice of numerous promising young officers whose lives were spent in vain." (Selahattin adil Paşa in his memoirs)

“Our initial task was to secure our defense by fortifying our positions until reinforcements could be mobilized, preparing for subsequent offensives. However, the Army Command adhered stubbornly to their own perspective. Upon the arrival of fresh units, they promptly deployed them to the frontline, initiating a series of consecutive night attacks. This misguided approach resulted in the loss of several seasoned and well-trained army units, along with the tragic sacrifice of numerous promising young officers whose lives were spent in vain." (Selahattin adil Paşa in his memoirs)

In pursuit of capitalizing on the Turks' weakened stance, the Allies initiated a fresh offensive on 6 May. The commencement echoed with naval gunfire at 10:30 am, marking the inception of the Second Battle of Kirte. British units advanced towards the right wing of the Turkish defense, while French forces simultaneously assaulted the left. Despite their strategic movements, the Allies encountered formidable Turkish resistance, stalling their progress at a mere 400 meters.

Undeterred, the Allies persisted with the offensive on the following day, only to find themselves in a déjà vu scenario. Progress remained minimal, with the troops advancing a few hundred meters and gaining control of some front trenches. This attempt at a breakthrough, however, was destined for failure. 8 May witnessed another futile push that failed to alter the inevitable outcome. Except for sporadic skirmishes on the Turks' left flank, the majority of Allied forces traversed the no-man's-land, often succumbing without encountering a single Turk.

Three days into the relentless struggle, the Allies found themselves still distant—3 km away—from the village of Kirte. However, the heavy toll was undeniable; 6,500 men had lost their lives. Amidst the losses, the sole achievement of note for the Allies was the capture of Hill 83 by the French.

Burying the Dead

The Turkish General Staff fervently advocated for a decisive offensive at the Arıburnu sector, envisioning the eradication of the adversary and the reclamation of the entire peninsula. Despite the entrenched positions on both sides and the evident protraction of the campaign, the resolve to press forward remained unwavering.

Enver Pasha, arriving at Çanakkale on 11 May, engaged in discussions with General von Sanders and Esat Pasha. Notably, Colonel Kazım Bey, the chief of staff of the Fifth Army, dispatched a cable to Enver Pasha, which regrettably went unnoticed. In this cable, Kazım Bey was pointing to the intentions of the Allies: “The enemy wants to weaken us by forcing us to attack. If we get weaker by repeatedly attacking them, they will counter this with larger and fresh forces and they will catch us tired and weak. The army must not get deceived by this.”

Enver Pasha, eager to confront and vanquish the enemy swiftly, resolved to deploy the 2nd Division, stationed in Istanbul under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Hasan Askeri Bey, to Gallipoli. The chosen date for the significant offensive was fixed on 19 May 1915.

The orchestrated plan entailed a Turkish assault on the Anzac beachhead, marshaling 42,000 troops. Esat Pasha exuded confidence in victory, buoyed by the Turks' numerical superiority over the Anzacs, who numbered approximately 17,000. The 19th Division aimed to strike to the north, the 5th Division at the centre, the 2nd Division advancing through Kırmızısırt-Kanlısırt towards the centre and south, while the 16th Division focused on Kanlısırt and the southern front.

The Turkish offensive commenced at 3:30 am, however, contrary to the Turks' anticipation, the Anzacs were not caught off guard, having gleaned intelligence from aerial reconnaissance and observations of Turkish front line preparations. Prior to the assault, the hushed stillness of the Turkish lines had been disrupted, alerting the vigilant Anzacs to the impending danger. In essence, the surprise element had eluded the Turkish commanders.

As the first light of dawn emerged, it became evident that the Turkish offensive had met with resounding failure. The majority of Turkish forces fell victim to the relentless barrage of machine gun fire as they sprinted towards the trenches. Despite a handful managing to breach the Anzac defenses, their efforts were futile; the thrust of bayonets could not alter the inevitable outcome. The Anzacs, already stirred and prepared, stood unwavering against the Turkish advance. This ill-fated episode marked a decisive setback for the Turkish forces on that historic day.

“The enemy fire caused several casualties, both as we occupied the trenches and when we attempted to evacuate. The construction of our trenches, unfortunately, hindered our ability to swiftly launch counterattacks. Compounding the challenge, the connecting trenches were overcrowded and subjected to continuous enemy fire. Undeterred by these formidable obstacles, our division displayed remarkable determination and made significant sacrifices as we launched an assault on the enemy positions. Regrettably, the intensity of the enemy's gunfire proved insurmountable, preventing our dedicated forces from reaching their targets alive. The space between the two trenches was filled with the bodies of martyrs.” (Major Burhaneddin Bey, who took part in the offensive on 19 May 19, in his memoirs)

As the sun ascended on that morning, half of the 2nd Division's soldiers lay sprawled across the no-man's-land. The 19th Division managed a modest advance of 15-20 meters, while the 5th Division struggled in vain to reach Merkeztepe until 10:00 am. Despite attempts to renew their attack throughout the day, Anzac machine guns dashed all hopes. In a mere four and a half hours, 3,855 Turkish soldiers met their demise, with 5,967 left wounded. Anzac losses, in stark contrast, amounted to 160 dead and 468 wounded. Although the Turks attacked with a force two and a half times the size of the Anzacs, by day's end, their losses were a staggering 16 times greater. The poorly planned assault had culminated in a tragic disaster.

Following the ill-fated 19 May attack, the no-man's-land became a haunting tableau of hundreds of corpses, primarily fallen Turkish soldiers, left exposed to the sun and beginning to decompose. General Birdwood, the Anzac forces' commander, urgently requested a supervised truce for the burial of the deceased, a plea that General von Sanders ultimately approved. As recounted by Esat Pasha in his memoirs: "The British were eagerly awaiting this. They found themselves in a precarious situation as the wind on the Gallipoli peninsula, typically blowing from north to south, carried the stench of the dead bodies directly towards them." The truce took place on 24 May, with soldiers from both sides interring the fallen in vast mass graves under the watchful eyes of Major Aubrey Herbert from the Allied forces and Major Ohrili Kemal Bey from the Turkish side.

Meanwhile, the Turks innovated a novel strategy, later adopted by the Allies. Tunnels, burrowed from friendly grounds towards enemy lines, concealed explosives beneath the adversary trenches. This method proved highly effective, wreaking havoc in the enemy's fortifications. The inaugural incident unfolded on 29 May at Bombasırtı.

Meanwhile, the Turks innovated a novel strategy, later adopted by the Allies. Tunnels, burrowed from friendly grounds towards enemy lines, concealed explosives beneath the adversary trenches. This method proved highly effective, wreaking havoc in the enemy's fortifications. The inaugural incident unfolded on 29 May at Bombasırtı.

Following minor skirmishes in late May, the Turkish 5th Division withdrew from the Arıburnu sector on 3 June. The mantle of responsibility now rested on the shoulders of the 19th Division, led by recently promoted Colonel Mustafa Kemal. The next day, Anzacs launched an offensive to impede Turkish reinforcement of the defence at Kirte village, strategically positioned in the southern reaches of the peninsula. British forces sought to breach Turkish lines and seize control of this vital village.

In the ensuing clash, New Zealanders successfully seized two trenches from the 57th Regiment, exacerbating the perilous situation. Liuetenant Colonel Mehmet Şefik Bey, commander of the 27th Regiment, recounted the events in his report: "I requested three valiant bombers from the commander of the 3rd Battalion. Corporals Hasan, Süleyman, and Mustafa responded. Laden with grenades in hands and pockets, I briefed them on the enemy's concealed firing position in the captured trenches. I directed them to a location shielded from machine gun fire, instructing them to crouch there and hurl grenades at the trenches. I assured them of due recognition for their actions. True to my instructions, these three soldiers executed the mission flawlessly." Although the trenches were reclaimed from the New Zealanders, one of the intrepid bombers sacrificed his life in the line of duty.

Bloodshed in Zığındere

On the same day, as the trenches shifted hands at Arıburnu, British forces at Seddülbahir embarked on their third endeavour to seize the village of Kirte. At 8:00 am, the thunderous roar of Allied naval gunfire echoed, assaulting the Turkish defensive lines. Despite inflicting considerable damage, the Turks, entrenched in a labyrinth of deep trenches, maintained their defensive prowess. Following the bombardment, Turkish units took strategic positions, patiently awaiting the imminent enemy advance.

Around noon, the Allied assault commenced. The 34th Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel Mehmet Ali Bey, successfully thwarted the French on the left wing of the Turkish defence. Simultaneously, the 36th Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Cemil Bey and the 22nd Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel İbrahim Bey, held their ground against the British at the centre-left. The 9th Division units at the central line also repelled the enemy forces. The right wing defence remained steadfast. By day's end, the Allied incursion had advanced no more than 1 km, compelling a retreat due to the absence of support. By 8:00 pm, the front had stabilized.

Turkish forces seized the initiative, launching a counterattack that repelled the Allies through successive charges, including a notable bayonet charge by the 2nd Division, which had faced tragedy at Arıburnu weeks prior but demonstrated resilience at Kirte. After three days of battle, the Allies achieved only marginal territorial gains. The cost of the Third Battle of Kirte was 7,500 casualties for the Allies and nearly 10,000 casualties, including 3,000 fatalities, for the Turks.

Realizing the futility of capturing Kirte and reaching the Kilitbahir Plateau, the Allies shifted focus to smaller, more manageable objectives. On 21 June, French forces targeted the western ridges of Kerevizdere. Despite being weakened and under-reinforced, regiments of the 2nd Division valiantly defended the area. The struggle persisted for two days, with the French penetrating 200 meters but failing to secure their objectives. Casualties mounted to 3,200 for the French and 6,000 for the Turks. Undeterred, the French launched a counteroffensive on 30 June, successfully capturing a pivotal position on the western ridges of Kerevizdere, a location they named Quadrilatére.

The Seddülbahir sector was in flames as 15,000 British troops launched an attack on both flanks of Zığındere on 28 June. Two hours of naval gunfire preceded the assault. Those positioned at the seaward side of Zığındere successfully seized some trenches, while their counterparts on the opposite side faced resistance from the Turks, who, launching a counterattack in the afternoon, halted the advance. This fierce battle persisted until the early hours of 30 June. Despite considering a retreat, the arrival of the 16th Regiment and the 1st Division, led by Lieutenant Colonel Cafer Tayyar Bey, altered the course of events.

There were also changes in the command structure. Responding to Enver Pasha's request, the Second Army initiated the dispatch of replacements to Gallipoli. Faik Pasha, Commander of the II Corps, assumed responsibility for the right wing, while Mehmet Ali Pasha, Commander of the I Corps, took charge of the left wing. Reinforcements in the form of the 3rd and 5th Divisions bolstered their ranks, setting the stage for a significant counterattack.

In the early hours of 5 July, a formidable Turkish force comprising 13,000 men launched an assault on Zığındere from both sides at 3:45 am. However, this offensive was swiftly called off in the face of relentless machine gun fire from the Allies. The culmination of these engagements marked the conclusion of the Zığındere battles, exacting a toll of 16,000 Turkish lives in just one week.

Following the Zığındere campaign, Vehib Pasha, the chief of staff of the Second Army, assumed command of the Southern Group, succeeding Colonel Weber. Despite his intentions to implement a significant structural overhaul in the defensive formation, Vehib's plans were thwarted by a renewed Allied offensive on 12 July. This decisive attack achieved its objectives, with the British seizing Turkish trenches and the French capturing Yassıtepe (Rognon). Over two days, Turkish casualties mounted to 9,575, while the Allies incurred losses amounting to 4,000.

By late July, the conflict on the Gallipoli peninsula reached a stalemate. Both sides entrenched themselves deeply, recognizing the futility of infantry charges against well-defended positions bristling with machine gun fire. The realization that such assaults were excessively costly led to a lack of significant progress for either side.

The main problem for the Turkish side was not a shortage of manpower but a critical deficit in artillery ammunition. General von Sanders consistently relayed this concern to Enver Pasha, highlighting the inadequacy in artillery supplies for weapons with high trajectories - essential for trench warfare. While the Turks possessed ample ammunition for guns with low or flat trajectories, these were ill-suited for the demands of the battlefield.

Throughout the three months following the April 25 landings, Turkish casualties reached a staggering 115,000, distributed between the southern and northern fronts, with 35,000 soldiers killed in action. In stark comparison, the Allied forces reported 75,000 casualties, with 29,000 men killed. The Turkish Fifth Army's infantry divisions bore the brunt of continuous combat, dwindling to regimental strength. Fortunately, reinforcements from the Second Army stemmed the tide, preventing a further erosion of Turkish defences. By the pivotal date of 28 July 1915, the Fifth Army commanded a total of 250,818 men. Despite its initial complement of six divisions, this number had surged to 17.

Defending the Heights

In late July, Allied decision-makers reached a pivotal moment. The Gallipoli campaign had reached a stalemate, with the Turkish lines proving impervious. Despite months of grueling trench warfare, they remained confined to small beachheads. The only options: withdrawal or a bold move to break the deadlock. They chose the latter.

The strategy unfolded with the decision to launch a second amphibious operation at Suvla Bay, northwest of Anafartalar. The objective: outflank the Turks and eliminate the Turkish Northern Group. This, they hoped, would isolate the Southern Group, pave the way to the Kilitbahir Plateau, silence the Dardanelles batteries, and open a passage to Istanbul for the Allied navy.

As Allied plans took shape, defenders of the peninsula anticipated the next move, uncertain about the precise location. Commanders like Liman von Sanders and Esat Pasha speculated that the invasion would come from the Gulf of Saros to the north, where substantial divisions and a cavalry brigade were stationed. Meanwhile, the Anafartalar Region Command, responsible for Suvla Bay, had a mere 3,000 troops under the command of German Lieutenant Colonel Wilhelm Willmer.

This limited force in a crucial area alarmed Mustafa Kemal Bey. He foresaw the Allied focus on Anafartalar, the vulnerable right wing of Turkish defence. However, his concerns fell on deaf ears, proving to be a significant error. The General Staff and the Fifth Army Command, failing to grasp the enemy's perspective, overlooked the strategic importance of the Kilitbahir Plateau as August dawned. Despite clear signs of an imminent Allied landing, they neglected the shores of Anafartalar, the surrounding hills, and the Kocaçimen mountain range, leaving them with inadequately defended units. This oversight would only be offset by subsequent serious errors made by the Allies in the later stages of the campaign.

The Hell That They Called Suvla Bay

On the evening of 6 August 1915, around 5:30 pm, amidst a relentless barrage from Allied warships and artillery in Arıburnu, British forces made landfall at Suvla Bay, situated to the north of the peninsula. The Turkish 16th Division's 47th Regiment, already depleted and weakened by the sustained bombardment, could not mount a robust resistance, enabling the swift arrival of British troops. Despite the Turks managing to impede the enemy's progress, the British forces, within two days, advanced to a mere kilometer from the landing beaches, successfully seizing Mestantepe (Chocolate Hill) and Karakol Dağı. However, the heights encompassing the Anafartalar plain eluded their grasp.

Simultaneously, on the very day of the British landing at Suvla, the Australians executed a bayonet charge, penetrating the initial line of Turkish trenches. A fierce day-long battle unfolded within a confined space, resulting in the loss of 1,000 Turkish soldiers and the relinquishment of the Kanlısırt Plateau (400 Plateau) by nightfall. Despite the subsequent efforts of two regiments from the 57th Regiment to reclaim the trenches, their endeavour met with failure.

Turks launched consequent counterattacks at Kanlısırt (Lone Pine) for three days without any outcome. Despite the relentless counterattacks, reinforcements swiftly arrived, bolstering the Turkish forces to a formidable 15,000 fresh troops. The pivotal recapture of Kanlısırt unfolded on 11 August, at the cost of 7,164 Turkish casualties, including 2,280 fatalities. In contrast, the Anzacs, penetrating a mere 150 meters, suffered a loss of 2,000 men. Meanwhile, diversionary British and French attacks in the southern sector, on 6 and 7 August respectively, faltered against the adept defence of strategically positioned Turkish units.