In the Balkan front, silence reigned until November 1915, when Field Marshal Mackensen orchestrated a joint offensive, marshaling German, Austrian, and Bulgarian forces for a decisive invasion of the rebellious Serbia. The strategic imperative behind this campaign was clear – Serbia stood as a formidable barrier on the path from Germany to Turkey. General Putnik and his beleaguered Serbian army, grappling with scarce ammunition and dwindling supplies, found themselves at the mercy of the relentless advance orchestrated by the Central Powers.

In the Balkan front, silence reigned until November 1915, when Field Marshal Mackensen orchestrated a joint offensive, marshaling German, Austrian, and Bulgarian forces for a decisive invasion of the rebellious Serbia. The strategic imperative behind this campaign was clear – Serbia stood as a formidable barrier on the path from Germany to Turkey. General Putnik and his beleaguered Serbian army, grappling with scarce ammunition and dwindling supplies, found themselves at the mercy of the relentless advance orchestrated by the Central Powers.

On 3 October 1915, the Anglo-French Expeditionary Force, comprising two divisions, made landfall in Salonica with the intent of bolstering Serbian resistance. Salonica, nestled within neutral Greece, bore witness to this incursion, yet the Greek government, limited to issuing mere protests, remained inert. The Allies harboured aspirations of offering the retreating Serbs sanctuary in Salonica, an ambition thwarted by the intervention of the Bulgarians.

With their overland route to Salonica severed, Serbian troops, facing dire circumstances, underwent a precarious evacuation from Albanian ports, finding solace in transit to the Greek haven via ferries. As the summer of 1916 unfolded, the Allied contingent in Salonica, under the stewardship of the French General Sarrail, burgeoned to a formidable force numbering 350 thousand men. This burgeoning force cast a looming shadow over the Central Powers' interests in the Balkans, particularly the vital railroad interlinking Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey.

In the brisk days of 26 May 1916, the Bulgarians breached the Greek frontier, their forces pressing forward with a determined pace. By the heat of August, their advance led them to the banks of the Struma River, shadowing the footsteps of the retreating Greek IV Army Corps. As the Balkan landscape echoed with the trudge of military maneuvers, the Allies, undeterred, seized the initiative, setting their sights on the strategic target of Monastir.

Amidst the shifting tides of war, on the decisive date of 12 September 1916, the German High Command, orchestrating the ballet of battle, turned to Enver Pasha. A call resounded for additional troops on the Balkan front, and on that very day, Enver Pasha responded affirmatively to the summons, his decision etching another chapter in the annals of conflict.

Immediate Entrainment

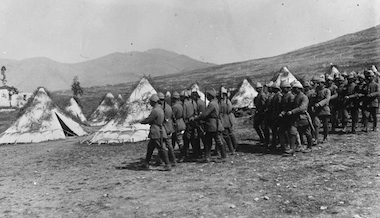

The 50th Infantry Division, stationed at Izmit west of Istanbul, received urgent deployment orders. Swiftly, troops moved to Üsküdar on the Asian side, traversing the Bosphorus by ferry, establishing camps in Bakırköy. On 21 September, the march to the Balkans commenced – a daily departure by train, concluding four days later as the last troops arrived in Drama, Greece, and the Bulgarian front at Salonica.

Under the command of Lt. Col. Şükrü Naili Bey, the 50th Division, on reaching its designated area, joined forces with the Bulgarian 10th Division. Their sector stretched from the mouth of the Struma River on the Aegean Sea, embracing the expanse between the Lake of Tahinos and Leftera Bay. Positioned at the forefront were the 158th and 169th Regiments, while the 157th Regiment stood in reserve. Faced with the formidable British naval presence in the Aegean, one battalion was strategically placed to guard the coastal flank.

As the sun set on the eve of 31 October, a formidable Allied offensive unfurled its might. British forces, pressing forward from the flanks of Tahinos Lake, bore down on the 169th Regiment positioned to the south. By nightfall, their persistent assault had brought them agonizingly close to breaching the initial defensive line. In a valiant stand, the Turkish unit fended off the onslaught, paying a steep toll of 19 lives lost and a staggering total of 113 casualties in a single day.

Undeterred by setbacks, subsequent endeavors unfolded. A coalition force comprising French, Serbian, and Russian troops embarked on a determined march in West Macedonia, confronting a resilient Bulgarian contingent steadfastly defending the rugged expanse. General Serrail, the architect of this offensive, harbored a singular ambition – the capture of Monastir. His strategic vision materialized on the pivotal date of 19 November, marking a significant triumph in the theatre of war.

One More Division

Amidst the ongoing Romanian campaign, the call for additional forces echoed. In response to the German plea, Enver Pasha directed the deployment of the 46th Infantry Division to Macedonia. Tasked to join forces with the 50th Division and the 16th Depot Regiment, their collective mission was to forge the newly minted XX Army Corps. At the helm of this corps stood General Abdülkerim Pasha, poised to lead the charge against the British. Simultaneously, the 177th Infantry Regiment underwent augmentation, transforming into the formidable Rumeli Field Detachment. Their destination: West Macedonia, where they would align with the Bulgarians, locked in combat against the French at the Monastir front.

Setting foot in Drama on 6 December, the XX Corps headquarters swiftly established connections with the 50th Division and their Bulgarian counterparts in the Second Army. Tasked with defending the Serez region, positioned north of the Tahinos Lake, the 46th Division assumed the mantle, relieving the Bulgarian 7th Division. A formidable task awaited, as the defensive line stretched over 30 kilometers. To fortify this critical expanse, Bulgarian artillery units and a cavalry squad were strategically integrated. The stage was set for a new chapter in the Macedonian theater of war.

In the winter of 1917, Macedonia lay in an unusual calm, devoid of significant military engagements. The XX Corps found respite, and for the ensuing three months, the theatre witnessed only sporadic skirmishes at the regimental level. Meanwhile, across various fronts, the Turkish army faced adversity — East Anatolia was under Russian control, British forces advanced toward Jerusalem, and an elite corps of 29,000 men idled in Macedonia.

Enver Pasha, seeking to retrieve his troops, persistently petitioned the German High Command. Finally, on the 10th of March 1917, an accord was reached, albeit for the return of a solitary division. The departure of the 46th Division commenced from Drama on the 19th of March, concluding its entrainment by mid-April. The narrative of the Turkish 46th Division's sojourn in the Balkans seemed little more than a European escapade. Upon reaching Istanbul, the division was swiftly redeployed to Mesopotamia.

April and May 1917 have been quiet at the banks of Struma River, yet in Mesopotamia, British forces made their move, seizing control of Baghdad. Faced with this threat, Enver Pasha swiftly organized the Seventh Army, a crucial force needed to defend Baghdad. The urgency was such that units stationed in Europe were immediately required. Following negotiations with the German High Command, the directive came to dispatch the 50th Division from Macedonia to Aleppo. With the departure of this division, the sole Turkish presence in the Balkan theater was now the Rumeli Field Detachment, specifically the reinforced 177th Infantry Regiment, which would maintain its position for another year.

Rumeli Field Detachment

On 29 December 1916, the Rumeli Field Detachment boarded the trains bound for Macedonia, reaching its destination in the town of Köprülü, just south of Skopje. This town held historical significance, as it was in 1908 that a young Major Enver boldly proclaimed independence, defying the Sultan's rule. Here, volunteers rallied, swelling the detachment's ranks to 4,300 strong.

Amidst the ongoing clashes between the French, who had seized Monastir, and the Central Powers, the Turkish unit received orders to position itself 15 kilometers north of the city, anticipating an imminent French offensive. Contrary to expectations, the French forces prepared for an assault not from the north, as the Germans anticipated, but rather from the western shores of the lake near the city. The stage was set for a pivotal confrontation.

On 13 March 1917, the French offensive unfurled, carving through a corridor stretching 10 kilometers in width and 16 in length, nestled between the lakes of Ohrid and Prespa. A critical juncture, for allowing their unhindered passage would imperil the Bulgarian 1st Army and the German 11th Army in the north. Swift action was imperative. The Turkish detachment received orders on the same day to mobilize towards the lake region, uniting with the Bulgarian 2nd Division.

The clash was imminent; the French 76th Division, buoyed by a considerable manpower advantage, faced off against the Bulgarians. Even with the reinforcement of Turkish troops, the odds stood at 15 French battalions confronting a meager six Central Powers battalions in defense. As the Rumeli Field Detachment reached Hotoshevo, situated west of Lake Prespa, the French relentlessly pursued the beleaguered German and Austrian battalions, battered from the earlier engagements.

The tide turned abruptly. A fierce Turkish onslaught, backed by a barrage of machine gun fire from both Turkish and German forces, injected panic into the French lines. A day of relentless combat ensued, resulting in a deadlock; the French advance was arrested, but not without exacting a heavy toll on both opposing sides.

With the stage set, it was now the Central Powers' turn to counterstrike. Bulgarian generals formulated a plan, omitting consultation with the Rumeli Field Detachment's commander, Maj. Nazım Bey. The strategy dictated a concerted effort to shove the French further south within the corridor, eyeing the pivotal Gorica-Trapezica line. The onus of the assault fell squarely on the Turkish detachment, with the prospect of others joining the fray contingent on an initial triumph.

At 2:00 pm on 1 April 1917, the assault commenced with a relentless barrage of artillery. As evening descended, Turkish infantry, facing formidable French entrenchments, pressed forward with determined bayonet charges. Despite their valiant efforts, the toll on their ranks was severe, prompting Major Nazım Bey to issue a command for the battalions to halt and consolidate their positions. The following dawn brought forth a relentless counteroffensive from the French, marked by intense artillery barrages and a determined infantry assault, forcing the Turkish forces to retreat to their initial positions.

The opening days of April 1917 saw Turkish casualties soar, with 712 men lost in the heat of battle. The subsequent weeks unfolded in relative quietude, as the inclement weather, compounded by snow, posed logistical challenges for both sides. However, the Turkish troops found solace in the warmth provided by their sturdy German-made uniforms.

The harsh cold was not the sole source of discontent among the Turkish forces. Having endured a staggering loss of nearly one-third of their manpower in the initial 18 days of engagement, they faced a stark contrast to their German, Austrian, and Bulgarian counterparts, who were stationed in less active regions and afforded moments of respite after intense combat.

In the face of the looming threat of trench warfare imposed by the French, Major Nazım Bey sought assistance from the Bulgarian 22nd Division and Colonel von Thierry, the German regional commander. His cables requesting a replacement for his detachment and a much-needed respite went unanswered, leaving him in increasing unease. Desperation led him to communicate the dire situation with the commander of the German 62nd Corps, yet the silence persisted.

Colonel von Thierry, infuriated by Nazım's persistence, filed a complaint against the major to Enver Pasha. Responding to the brewing discord, Enver requested a detailed report from Major Nazım Bey. The report illuminated the Germans' apparent double standards. Seeking resolution, Enver appealed to the German High Command for the return of the Rumeli Field Detachment to Turkey. Regrettably, this plea fell on deaf ears.

Feeling slighted, Major Nazım Bey, who had exerted his utmost efforts, found the situation worsening. Even the basic necessity of finding drinking water became a daunting challenge for Turkish soldiers. While Enver Pasha viewed Nazım's concerns with skepticism, the major's resignation on 10 July spoke volumes. His departure marked the end of an era, with Lieutenant Colonel Ali Bey stepping into his shoes on 28 July.

In August, following minor skirmishes, Lieutenant Colonel Ali Bey sought respite from the German 62nd Corps command. His request was denied, and instead, he was tasked with a night assault to capture a hill on the front line. On 5 September, this daunting mission was accomplished, albeit at a cost of 41 Turkish and two German lives.

for Ottoman victory

Undeterred, Ali Bey persisted in informing Istanbul, as well as the Bulgarian and German commanders, about the challenging conditions. On 6 October, the Ottoman High Command issued an order for the Rumeli Field Detachment to prepare to return to Turkey. However, the soldiers' jubilation was short-lived. Just two days later, Enver Pasha transmitted a contradictory cable: "Order for your return to Turkey is cancelled."

The abrupt shift in orders remains shrouded in mystery. The persistence of the German High Commander in retaining the Turkish detachment raises questions, hinting at potential political complexities. The months of October and November 1917 passed quietly, marked by worsening winter conditions for the Turkish troops. Ali Bey continued his efforts, corresponding with German, Bulgarian, and Turkish commands.

On 23 November, his perseverance bore fruit. A telegram from General Ludendorff, second only to Hindenburg in the German High Command, directed the replacement of the Rumeli Field Detachment with a Bulgarian regiment, signaling their move to another front.

Rest eluded them for a mere month; instead, the detachment lingered in Prilep until 11 February 1918. During this period, amidst training, the leadership underwent a change – Lieutenant Colonel Ali Bey yielded his position to Lieutenant Colonel Sadık Bey. February saw their return to the lake region, yet the echoes of war grew faint, signaling its impending conclusion.

By May 1918, the Rumeli Field Detachment received orders to retreat to Turkey. At the close of June, the troops embarked from the Romanian port of Costanza, ferrying across to Batum on the East Black Sea coast. There, they were destined to join the Third Army, marking the end of the Ottoman Empire's presence in European theaters during the First World War.

In retrospect, it's not an exaggeration to assert that the dispatch of the XX Army Corps to Macedonia yielded little. At a time when fresh forces were direly required on other fronts, 25,000 men idled away their days in the Balkans. A colossal misstep, a needless squandering of manpower. In stark contrast, the Rumeli Field Detachment emerged as a dynamic and triumphant force, asserting dominance over the French in the lake region around Monastir.

![]()

Sources consulted:

- Ertem, Ş., “Avrupa’da Yüz Bin Türk Askeri” (Hundred Thousand Turkish Soldiers in Europe), Kastaş Yayınları, Istanbul, 1992.

- Official History, “Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nda Türk Harbi – Avrupa Cepheleri” (Turkish Battles in the First World War – European Fronts), Genelkurmay Yayınları, Ankara, 1996.

PAGE LAST UPDATED ON 3 JANUARY 2024