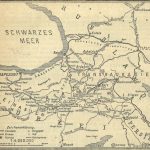

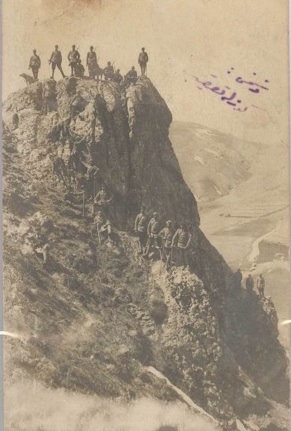

he Caucasian campaign unfolded in the rugged expanse of Northeast Anatolia, a terrain marked by towering mountains and expansive plains. It is a region where mighty rivers find their origins: the Euphrates, meandering towards the Persian Gulf; the Aras, carving its path to the Caspian Sea; and the Çoruh, gracefully flowing into the Black Sea. This untamed land bears witness to harsh climates, with most peaks surpassing the 3,000-meter mark. The descent of snow commences in early September, accumulating up to 1.5 meters on the ground. Amidst a blizzard, daylight surrenders to an inky darkness, limiting visibility to a mere five meters. The mercury can plunge to temperatures below -30 degrees Celsius.

In the earlier epochs of the 20th century, this region was inhabited by Anatolian Turks and a notable contingent of Armenians. Despite its vastness, the population density here remained comparatively low, distinguishing it from other parts of the Empire. The epicentre of wartime activities stretched across the domain between the Lake of Van and the Black Sea.

The intricacies of the terrain rendered it unfavourable for offensive manoeuvres, yet it offered strategic advantages for defensive strategies. The western domain fell under the jurisdiction of the Turkish Third Army, while the eastern expanse was overseen by the Second Army. The geography, challenging as it may be, became a theatre of historic significance during this pivotal chapter in history.

October 30, 1914 was the first day of the Islamic religious feast and in Erzurum, where the headquarters of the Third Army was located, and oy resonated among Turkish troops stationed in Erzurum, home to the Third Army's headquarters. However, the festivities abruptly ceased as a cable arrived from Istanbul's High Command. An exchange of fire between Russian and Turkish vessels in the Black Sea had transpired, and the Imperial Russian Army loomed on the Ottoman border.

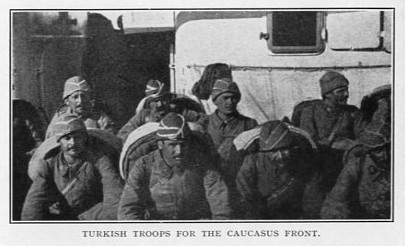

Under the leadership of Hasan İzzet Pasha, the Third Army comprised the IX, X, and XI Corps. Erzurum hosted the headquarters alongside the IX Corps, while the X Corps was positioned in Sivas, and the XI Corps in Mamuretülaziz. Spanning 1250-1500 kilometres, the Third Army's territory grappled with inadequate transportation infrastructure. The manpower, a formidable 190,000, included regular troops (83,000), reserves, Erzurum Fortress personnel, transportation units, depot regiments, military police, and an accompanying 60,000 animals.

The Russian offensive commenced on 1 November 1914, a day prior to the official declaration of war. The Russian I Corps ventured from Sarıkamış towards Köprüköy, while the Russian IV Corps progressed from Yerevan to Pasinler Plains. By 4 November, Russian forces had reached Köprüköy and simultaneously advanced along the Karaköse-Muratsuyu line. The Russian juggernaut boasted 25 infantry battalions, 37 cavalry units, and 120 artillery guns. The stage was set for a pivotal chapter in history.

On the day of the Russian offensive, orders from Enver Pasha reached the Third Army headquarters: “The enemy does not appear superior. The X Corps requires an additional 2-3 weeks to reach the frontline. To buy time and boost army morale, I contemplate launching separate attacks on the enemy. You will strike to the rear of the Russians, Kurdish Tribal Regiments will infiltrate beyond enemy lines, and the forces in Van will assail Persian Azerbaijan.” Hasan İzzet Pasha opposed an offensive in harsh winter conditions, intending to remain on the defensive, lure the Russians to the Erzurum Fortress, and counterattack at an opportune moment. However, immediate attack orders left him no choice.

The main Russian attack occurred along the Erzurum-Sarıkamış road, supported by a robust assault from Oltu. On 7 November, the Third Army initiated its offensive with the XI Corps and all cavalry units. Unfortunately, this attack lacked organization; the cavalry failed to execute the encircling manoeuvre, and the Kurdish Tribal Regiment proved disappointing. Following the withdrawal of the 18th and 30th Divisions, the Russians gained ground. In consultation with his German chief of staff, Colonel Felix Guse, Hasan İzzet Pasha contemplated a retreat to Erzurum to prevent further losses. However, XI Corps commander Galip Pasha objected and convinced Hasan İzzet Pasha against retreating. Turkish forces held their ground at Köprüköy, concluding the First Battle of Köprüköy without a clear victor.

On 12 November, the IX Corps, led by Ahmet Fevzi Pasha, bolstered the XI Corps on its left flank, initiating a pivotal shift in the course of the conflict. Supported by cavalry, Turkish forces, contending with the harsh elements of a snowstorm, began a relentless push against the retreating Russians in the Second Battle of Köprüköy.

Navigating treacherous rocky hills and traversing frozen rivers, the troops, braving freezing waters, triumphantly occupied Köprüköy. This strategic gain, however, yielded minimal advantages in the broader context of the campaign. The Russians, compelled to retreat, faced the formidable resilience of the 3rd Infantry Regiment.

The unfolding events led to the subsequent Azap Offensive from 17 to 20 November. A mounting sense of anxiety gripped the Russian forces as their commanders, in communication with the High Command of the Caucasian Army in Tbilisi, conveyed a grim assessment of impending defeat. Simultaneously, the Third Army faced adversity in deteriorating weather conditions, coupled with substantial Turkish casualties – 9,000 killed, 3,000 taken prisoner, and 2,800 deserters.

Eyewitness accounts reveal the strain on Hasan İzzet Pasha, teetering on the brink of a nervous breakdown. Despite territorial gains, the Turkish forces confronted the harsh reality of the unyielding climate. Ordered by the High Command in Istanbul to press on with an offensive, Hasan İzzet Pasha grappled with the challenge of orchestrating an effective manoeuvre under such adverse conditions.

By the close of November, a fragile stability settled over the front, with the Russians entrenched in a salient 25 kilometres deep into Turkish territory along the Erzurum-Sarıkamış axis. The theater of war, shaped by these intricate battles, witnessed a delicate balance amid the unforgiving elements and strategic imperatives.

On 8 December, Colonel Hafız Hakkı Bey, the assistant chief of staff of the Ottoman Army, sailed into Trabzon aboard the cruiser Mecidiye. His mission, dispatched by Enver Pasha, aimed to invigorate the Third Army. Contrary to the defensive strategy envisioned by Hasan İzzet Pasha to endure the winter and initiate an offensive in the spring, Hafız Hakkı swiftly directed the planning of a new offensive.

Despite reservations from Hasan İzzet Pasha and corps commanders regarding the practicality of this plan, a cable dated 18 December 1914 revealed his concerns to Enver: “We must allocate eight or nine days for a large-scale encircling manoeuvre. However, during this time, the XI Corps, stationed at the front, might be compromised. Even with two corps executing the manoeuvre, they will likely encounter difficulties against the enemy.”

Enver Pasha sought the complete annihilation of Russian forces through a winter offensive grounded in an encircling manoeuvre. Taking command, he departed Istanbul for the Caucasian front, arriving in Erzurum on 21 December. Accompanying him were General Bronsart von Schellendorf, the chief of staff of the Ottoman Army, his assistant Kazım Bey, and the head of the operations office, Lieutenant Colonel Feldmann.

Convinced that Russians could be encircled and annihilated in Sarıkamış, Enver was disturbed by Hasan İzzet’s cable. When these two generals, each harboring divergent perspectives on the campaign, met in Köprüköy, Enver could not conceal his disappointment. This encounter, vividly recounted by Kazım Bey, not just the assistant to the chief of staff but also Enver’s brother-in-law, portrays Enver's pointed words to Hasan İzzet: “Mistakes have been made, and you have faltered. The Russian Army was meant to face annihilation here. Now, you must take immediate action to obliterate the Russians at Sarıkamış.”

Hasan İzzet Pasha, having exhausted his patience, retorted, “This is impossible! Survey the surroundings yourself. It is winter, amid snowstorms. In such conditions, at this time of year, a military operation is destined for failure. I will annihilate the enemy once winter yields and roads become passable.” Enraged by these words, Enver thundered, “I would have you executed if you were not my teacher” – it's noteworthy that Hasan İzzet Pasha had served as Enver’s instructor at the Staff School. Due to his reluctance to initiate an attack, Hasan İzzet Pasha found himself compelled into retirement, Enver Pasha appointing himself as the commander of the Third Army.

Enver aspired to replicate Germany's triumph at Tannenberg, employing a similar manoeuvre strategy. Yet, a crucial oversight lingered—Sarıkamış presented markedly disparate conditions compared to Tannenberg. The treacherous terrain, cloaked in the chill of Caucasian winter, stood in stark contrast to the European summer environs of the former. Furthermore, the Turkish Army, lacking the robust equipment of their German counterparts, faced a distinct disadvantage. Nevertheless, the German High Command endorsed Enver's strategy, prioritizing the diversion of Russian forces from Poland to fortify their operations in the Caucasus.

General Liman von Sanders' memoirs provide intriguing insights into this juncture: "Prior to the commencement of the Caucasian campaign, Enver elucidated his plans to me in detail. Concluding our meeting, he revealed his ambitious, albeit somewhat peculiar, intentions—to march towards India and Afghanistan upon concluding operations in the Caucasus."

Simultaneously, a specialised detachment emerged from the 3rd Division stationed in Thrace. Assigned to the vicinity of Çoruh, its mission aimed to confine Russian forces along the Batumi coast. This strategic maneuver allowed the X Corps to pivot from defensive coastal operations to a concentrated offensive stance. Commanded by German Major Stange, this detachment earned the moniker "Stange Bey Detachment."

Discontent with the leadership of the Third Army, Enver Pasha instigated further changes. Colonel İhsan Bey replaced Ahmet Fevzi Pasha, commanding the IX Corps, while Colonel Hafız Hakkı Bey succeeded Ziya Pasha as the commander of the X Corps. Both new commanders lacked operational experience.

Sarıkamış Disaster

The Turkish Operation Plan proposed a single envelopment using three corps. On the right flank, XI Corps would engage the Russians and carry out feint attacks. In the centre, IX Corps would advance towards Sarıkamış Pass. Hafız Hakkı’s X Corps, on the left flank, aimed to reach Oltu, traverse the Allahüekber Mountains, sever the Kars road, and force the Russians into the Aras Valley, where all three corps would coordinate to annihilate them. Simultaneously, the Stange Bey Detachment would conduct conspicuous operations to distract and immobilise Russian units.

Filled with anticipation, Hafız Hakkı eagerly awaited the attack. In a letter to İhsan Pasha, dated 19 December 1914, he revealed overly ambitious plans lacking solid foundations: “The IX and X Corps must reach Sarıkamış and Kars before the Russians. To achieve this, two conditions must be met: a sudden initial attack and swift advancement after its conclusion. I plan to crush the enemy within one or two hours and then proceed to Oltu… The assault at İd should end by the afternoon on 22 December. Subsequently, we will cover 30 kilometres daily, reaching the Kars-Sarıkamış line by 25 December.”

As the major offensive unfolded, the Third Army's offensive strength comprised 118,660 men, 73 machine guns, and 218 artillery pieces. Turkish intelligence estimated the Russians' rifle strength at approximately 65,000.

On 22 December 1914, hostilities ignited, setting the stage for a pivotal moment in history. The X Corps commenced its movement towards Oltu, swiftly occupying the town the following day. In this strategic advance, around one thousand Russian troops succumbed to capture, accompanied by the seizure of four artillery guns and four machine guns. Simultaneously, IX and XI Corps pressed forward in their own determined pursuits.

However, the second day of the campaign witnessed an unfortunate incident. For nearly four hours at Narman, the 31st and the 32nd Divisions found themselves unwittingly engaged in combat. This significant error is attributed to map-related challenges. By 24 December, the X Corps had surmounted Oltu after covering a grueling 75 kilometers in just over three days. At this juncture, the Corps prepared to pivot southeastward, orchestrating a move to outflank and envelop Sarıkamış.

On 25 December, Enver Pasha issued a historic order-of-the-day, reporting triumphs and outlining future strategies. The capture of one thousand men, officers, and a colonel, along with six cannons, four machine guns, rifles, and other equipment, marked a decisive victory at Oltu. Meanwhile, the IX and X Corps exerted influence over their sectors, compelling some enemy forces towards Ardahan and driving others into the mountains.

Enver Pasha's directives for the army were clear and resolute. The roadways connecting the enemy with Kars were to be severed, and on 25 December 1914, the 29th and the 17th Divisions of IX Corps were slated to arrive in Sarıkamış. A repositioning of the front line to the southeast was to occur, with a specific focus on occupying passages and the town itself. The 28th Division received orders to secure Bardız and fortify against potential attacks from the Yeniköy direction.

As the X Corps set its sights on Sarıkamış, plans were underway, and the army command awaited updates on their movement. Meanwhile, the XI Corps and the 2nd Cavalry Division temporarily operated without specific orders, tailoring their actions to align with overarching objectives. Should the enemy retreat, destruction awaited them at Sarıkamış; if they halted, the IX and X Corps were poised to launch an attack from the rear.

The army headquarters, stationed in Bardız until noon on 25 December, anticipated relocating to Sarıkamış, where it would spend the following day, 26 December. These strategic moves and decisive actions etched a chapter into the annals of history, shaping the course of events in this significant theatre of war.

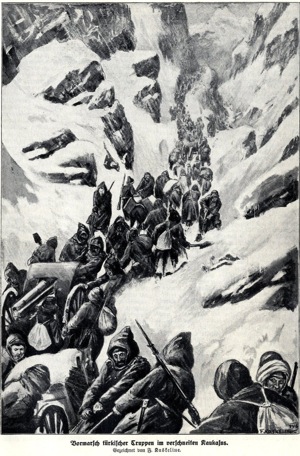

At 7 a.m. on 26 December, the 29th Division set out from Bardız. Despite the absence of falling snow, the Bardız Plain was already cloaked in a layer of snow, reaching the soldiers' knees, making the journey exceedingly challenging. The animals pulling the howitzers found themselves stuck in the snow, compounding the difficulty of the trek. Despite these hardships, Colonel Arif Bey, the division commander, suggested a break at the village of Kızılkilise. However, Enver Pasha urged them to press on.

The troops were ill-equipped for the harsh conditions, lacking proper footwear and relying on nothing more than sandals. These makeshift shoes, when soaked, transformed into icy encumbrances around the soldiers' feet. Despite the suboptimal conditions, they were denied breaks to warm themselves around a campfire. Struggling to prevent frostbite, some soldiers found it impossible. Frostbite first gripped their toes, then their wrists. A few more steps on the snow, and their wrists were immobilized, with the frostbite spreading to the rest of their bodies. This grim fate awaited many Turkish youth on the plains of East Anatolia.

By afternoon, the Russian positions came into view. Colonel Arif Bey approached the corps commander, Colonel İhsan Bey, proposing a night's rest for the troops to recuperate before launching an attack at dawn the next day. İhsan Bey agreed, but Enver persisted with plans for a night assault, overlooking the fact that the battalions were reduced to less than 200 men and the temperature stood at 26 degrees below zero. The Allahüekber Mountains resembled a white inferno of snow in the darkness, with the silence of death enveloping the scene.

On that fateful night, the valiant 86th and 87th Regiments successfully repelled the Russian forces, claiming the strategic hill Çamurludağ. Initially, the Turkish officers believed Sarıkamış was situated just beyond the hill, but a swift realization dawned – the town lay 8 kilometres away, a misjudgment attributed to the inadequacy of the maps. Thankfully, reinforcements were on the horizon, as the 17th Division reached Çamurludağ after an arduous 22-hour march.

Simultaneously, under the command of Colonel Hafız Hakkı, the units of the X Corps pressed forward, marching for an exhausting 14 hours. Fatigue and hunger had replaced the initial fears of frostbite and Russian machine guns with an overwhelming indifference. In the early hours of 26 December, during the eighteenth hour of their relentless march, the 91st Regiment of X Corps encountered enemy fire. After nearly two hours of fierce combat, the Russians withdrew, allowing the regiment to resume its journey just as a snowstorm enveloped the surroundings. Despite the challenging conditions, the 91st Regiment reached Kosor 21 hours after departing Penek, covering a mere 8-kilometre distance. Similar progress was observed among other units, with some finding rest in the villages of Kosor, Arsenik, and Patsik – 40, 35, and 30 kilometres from Sarıkamış respectively. Ahead of them loomed the formidable Allahüekber Mountains, demanding at least two additional days to reach Sarıkamış.

On the morning of 26 December, Enver Pasha, General Bronsart von Schellendorf, and other senior officers peered through their binoculars, observing Sarıkamış. Veiled within the misty forests of Çamurludağ, the village of Çerkezköy marked the proximity to Sarıkamış. The town, adorned with a train station, Russian barracks, and towering churches, stirred to life on that wintry day. Enver Pasha's strategy unfolded as he aimed to seize the town with IX Corps, subsequently encircling the Russian forces and thwarting any retreat to Kars, thus ensuring their annihilation.

The attack was launched at 7:30 am. Russian forces strategically positioned themselves in the northern forests of Çerkezköy, awaiting the impending advance of Turkish troops. The air was charged with tension as Turkish soldiers pressed forward, only to be met with an unrelenting barrage of heavy machine gun fire. Simultaneously, Russian artillery relentlessly pounded Turkish howitzers, rendering their counterattacks futile.

Throughout the day, the battlefield echoed with the sounds of conflict. As the sun dipped below the horizon, İhsan Pasha, the commander of IX Corps, approached Enver Pasha with a grave assessment: "Our forces for assault are inadequate, and reserves have been depleted. The Yeniköy road is vulnerable, risking the enemy's occupation of Çamurludağ and our rear positions. Without reserves, unit relocation is impossible. May we regroup overnight, restoring order and launching a new offensive tomorrow morning?" Enver Pasha, acknowledging the stark reality, approved the proposal.

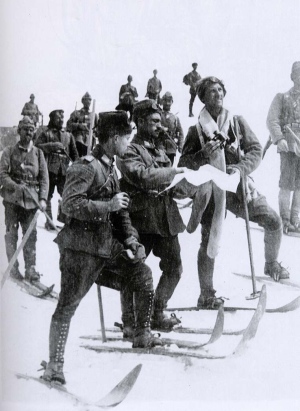

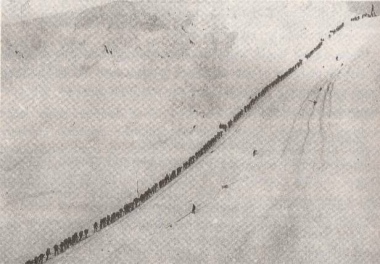

After spending the night of December 25/26 in three villages, the men of X Corps, comprising the 30th, 31st, and 32nd Divisions, encamped in three villages. At 5 am, the corps set forth on a challenging journey, scaling the formidable Allahüekber Mountains. There was no snow falling on the mountains and the sun was shining. The higher the troops climbed, the stronger became the wind and the colder it got. Progressing through thick snow proved arduous, leading soldiers to succumb one by one. A chilling spectacle unfolded, visible to those in the rear—a procession of grey dots ascending, one row advancing slowly, the other standing motionless. The immobile column, a grim testament to the toll of the ascent, grew in size as they ascended.

Fatigue, hunger, and sleep deprivation plagued the troops, compounded by inadequate winter attire. Harsh conditions left them with little chance for survival. Exhausted soldiers dropped to their knees, deprived of energy, unable to move or speak. Dizziness enveloped them, ushering in a deep slumber from which they would never awaken. Thus, the unforgiving terrain etched a somber conclusion to a fateful journey, marking the beginning of the end.

In a grueling odyssey lasting 14 harrowing hours, the infamous "death march" concluded, and the remnants of X Corps persevered to attain their initial goal – the quaint village of Beyköy. A somber headcount ensued, revealing a staggering casualty rate of 90 percent. Merely 1,400 valiant men from the 30th Division successfully reached Beyköy, while the unforgiving mountains claimed the lives of 15,000 souls. This grim toll mirrored the fate of the other two divisions; countless lives lost, not a single bullet fired in battle.

"We left the village when it was still dark. The privates were following the corporals in complete silence. We had local guides and according to the maps we had, we believed we could reach the summit in three hours. We walked twice that long, and the road was still going up. As we climbed higher, the scenery became wilder, but more beautiful. It looked as if the whole place was made of endless snow and rivers. We could see the hills covered with snow and ice below us. I could not imagine how our artillerists could make it up this steep snowy mountain. We were climbing under difficult circumstances but we kept order and discipline. Finally, we reached the highest point, which was a wide snow plain... We were exhausted. A sharp wind blew over us, and then came a snowstorm. Visibility was nil. Nobody could speak or say anything, let alone help each other. The long marching column dissolved. Soldiers went away wherever they could see a black point at the edge of a forest or a riverbank, any place where they could see smoke from a fire.The officers tried hard, but no one listened to them. I can still remember the scene. A private kneeling in the snow beside the road, screaming, wrapping his arms tightly around a pile of snow, biting it and scratching it with his finger nails. I tried to help him stand up to take him back to the road. He did not respond at all and he kept on doing it. The poor man had gone mad. We left more than ten thousand souls like that, in one single day under the snow in those cursed glaciers." (An officer from the 93rd Regiment of the 31st Division, in his memoirs)

The 93rd Regiment, originally consisting of 5,000 troops, arrived at the village of Başköy with a mere 300 men. To avert a similar fate for other regiments, Colonel Hasan Vasfi Bey, commander of the 31st Division, issued a crucial directive. The order stated that the initial instruction for all units to reach Başköy that night was impractical. The distance between Arsenik and Başköy, spanning over 7 hours of walking through a winding plain, was treacherous. The icy conditions claimed both men and animals, their lifeless forms scattered along the road. Colonel Hasan Vasfi Bey, witnessing the heartbreaking scene, deemed attempting the crossing at night tantamount to murder. In light of this, a new plan unfolded. Units that had already departed Arsenik were advised to spend the night in a vast pine forest west of the plain, towards the village of Yayla. They were instructed to light fires for warmth, refraining from sleep to stave off frostbite. The following day, they could continue their journey to Başköy. Additionally, a rest day was declared for all units on the subsequent day. For those yet to leave Arsenik, the directive advised securing experienced guides and using the Issızdere road.

The dawn of the next day brought forth the true extent of the calamity. Only 3,400 survivors emerged from the 30th and 31st divisions out of an original 32,300, most of them ailing. The 32nd Division found itself immobilized in Bardız, facing a formidable Russian force. The Russians had effectively divided the 30th and 31st divisions in the rear.

In response to Enver Pasha's commands, Colonel Hafız Hakkı rescinded the scheduled rest day. Instead, he ordered the remnants of his corps to shift to the Divnik-Çatak line, aiming to eliminate the Russian units at Novoselim and encircle the ostensibly retreating enemy from Sarıkamış. Contrary to expectations, the Russians were fortifying their defenses in Sarıkamış. Concurrently, Enver Pasha personally directed the 29th Division of the IX Corps to launch a renewed assault on the Russian positions surrounding Sarıkamış.

In the waning days of December 1914, the 87th Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Lütfullah Bey, achieved a momentary triumph as they entered Çerkezköy. Regrettably, their elation was short-lived, as they soon found themselves ensnared within the village. Colonel Barkovski's Russian unit had not relinquished its hold on Çerkezköy. Daylight witnessed continued skirmishes, and by the following morning, Turkish forces in Çerkezköy succumbed, becoming prisoners of war.

Recognizing the futility of pressing forward into Sarıkamış with the IX Corps alone, Enver Pasha opted for patience. December 28 was declared a day of respite, awaiting the arrival of Colonel Hafız Hakkı’s X Corps. Meanwhile, the X Corps reached the Sarıkamış-Kars railroad, obliterating the tracks in their wake. Simultaneously, the 31st Division arrived at Sarıkamış. However, Colonel Hafız Hakkı was met with a disheartening sight – a mere 1,000 weary soldiers remained from the initial 14,000-strong division. Deciding to regroup and conserve energy for a renewed offensive, a retreat was ordered.

As Turkish forces approached the village of Yağbasan, they encountered a barrage of Russian machine gun fire. A brief but intense clash unfolded before the Russians withdrew back to Sarıkamış, setting the stage for the unfolding drama of this historic campaign.

Enver Pasha was with the IX Corps, where the frustration of Commander İhsan Pasha stemmed from Enver's frequent interventions in command. Observing Enver's unwarranted optimism, İhsan Pasha, limited in his actions, could only present the stark facts. On 28 December, he submitted a detailed report on the corps' current situation to Enver Pasha, who, in response, asserted, "Today I witnessed corps and division commanders in the rear. All must be at the front. Our reports consistently mention low manpower. I personally observe that Russian companies also lack more than 20 men."

Enver Pasha was thinking that the Russians were retreating to Kars. In fact, what Enver thought to be a retreat, was actually an encircling movement. He was delighted, but this feeling was soon replaced with disappointment when a Russian prisoner of Turkic origin was brought to his presence. The prisoner said: “Russians are preparing to encircle your forces at Sarıkamış with a force of five regiments.” This shock enabled Enver Pasha to see the truth. The IX Corps, which reached Sarıkamış, had melted away. The X Corps, which was supposed to come to the rescue, had lost 90 percent of its men on the slopes of Allahüekber Mountains. The XI Corps was at the Aras region, fighting the Russians there. A regiment entering Çerkezköy became captive, leaving the Russians poised to encircle the remaining Turkish forces.

29 December witnessed Hafız Hakkı's efforts to reclaim Sarıkamış with the remnants of the X Corps. The initial attempt by the 88th Regiment was repelled, followed by the 31st Division's organized offensive. Colonel Lange, a German officer, attacked from the south, while Colonel Hasan Vasfi launched an assault from the north, reaching the defensive line just 250 meters from the town. Despite strong Russian resistance, a renewed attack around 4 pm showcased high Turkish morale, realizing it was their last chance. The surprised Russians panicked, abandoning their positions and retreating to the town, leading to street fighting in Sarıkamış. Turkish soldiers engaged in both combat with the Russians and the search for sustenance.

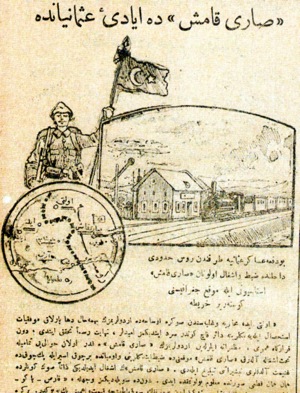

of the train station in Sarıkamış • Tasvîr-i Efkâr, 4 January 1915

That day, the first good news from the Caucasus arrived in Istanbul. Ardahan was taken. Embarked on the warship Yavuz from Istanbul, the Stange Bey Detachment disembarked in Rize, subsequently bolstered by nearly two thousand volunteers. Their journey southwards culminated in the occupation of Ardahan on 27 December. However, the detachment, valiant but outnumbered, succumbed to three Russian infantry regiments and one cavalry regiment a few days later. Despite the setback, the resilient "-Stange Bey Detachment held its ground against the Russians for over two months, ultimately retreating to its original position on 1 March 1915.

By the evening of 29 December, Turkish forces had seized control of the western fringes of the town, including the train station and the barracks of the Russian Yelizavetpolski Regiment. General Prejevalski, the Russian forces' commander in Sarıkamış, faced a pivotal moment and resolved to deploy his last reserves in a final effort to dislodge the Turks from the town. Colonel Temrin, his chief of staff, exhibited remarkable courage, capturing the train station through a bayonet charge. With the tide turning in their favour, the Russians compelled Turkish troops to vacate the town, marking a crucial chapter in this historic encounter.

On 30 December, the resonating echoes of Russian artillery inflicted severe casualties, casting a somber shadow over the battlefield. Enver Pasha, confronted with the harsh reality, received two concurrent reports. One emanated from the chief of staff of the IX Corps, Lieutenant Colonel Şerif Bey, while the other was delivered by Colonel Hafız Hakkı Bey. Both narratives echoed a consistent refrain – the corps stood bereft of the strength required for another offensive thrust. In the face of this vulnerability, Enver's unwavering response reverberated: "The offensive is to go on at full strength."

As 1914 drew to a close, disheartening tidings emanated from Bardız, etching a poignant tale. The 32nd Division, under duress, yielded its positions to the advancing Russians. With Bardız and Kızılkilise roads slipping into the grasp of the adversary, Turkish forces found themselves ensnared within a precarious semi-circle. While a strategic retreat through the open mouth of the encirclement beckoned rationality, Enver Pasha, undeterred by caution, opted for audacity, commanding an attack against the tightening noose.

Simultaneously, some 40 kilometres south of Sarıkamış, the XI Corps, under the leadership of Galip Pasha, orchestrated renewed assaults on Russian lines. This manoeuvre sought to alleviate the mounting pressure on the beleaguered IX and X Corps stationed before Sarıkamış. Slowly succumbing to the unfolding reality, Enver Pasha redirected his focus. Rather than persisting in futile offensives for Sarıkamış, he sought to secure retreat routes. Merging the two corps, he christened the amalgamation as the "Left Wing Army," entrusting the command to the newly promoted Brigadier General Hafız Hakkı, now bestowed with the honorary title of "Pasha."

Hafız Hakkı Pasha anxiously awaited reinforcements, still holding onto the hope of seizing Sarıkamış. Despite the impending Russian advance, he refrained from ordering a retreat. The situation grew dire as the encirclement tightened. On the afternoon of 4 January, after surveying the front line on horseback, he returned to headquarters and solemnly declared in French, "Tout est perdu, sauf l’honneur" (Everything lost, except honour). A fleeting smile accompanied his admission to İhsan Pasha in Turkish, "It is over." There had lingered a glimmer of optimism for the troops on Allahüekber Mountains, but alas, none survived.

Abruptly, the headquarters fell under Russian fire as the entire 28th Division succumbed to capture. Hafız Hakkı Pasha narrowly escaped, but eight high-ranking officers, including İhsan Pasha, surrendered. The 17th and 29th Divisions met the same fate, comprising 108 officers and 80 soldiers transported to Sarıkamış. Meanwhile, Hafız Hakkı Pasha, safely ensconced in the X Corps headquarters, learned of the Russians overrunning the IX Corps, prompting a decisive order for a total retreat. At dawn the next day, they commenced their march towards Erzurum.

It took four days for Enver Pasha and the German officers accompanying him to reach Erzurum. In a cable to Istanbul, he reported, "Although the offensive against the Russians has not conclusively defeated the enemy, it has driven them beyond our frontiers, secured parts of their territory, and inflicted damage on their army. Our immediate focus is on granting our army reprieve after fifteen days of relentless fighting, followed by a renewed offensive. Departing for Istanbul, I entrust the army's command to Hafız Hakkı Pasha, urging utmost confidentiality regarding these developments and my departure."

"Friends, for nearly one month I have been with you and I saw how you attacked the enemy in battles which went on for days. Although the weather was harsh, you ignored all kinds of poverty and broke the resistance of the enemy. You drove the enemy out of the motherland and you took enemy territory. These efforts of yours will never disappear. The entire nation, including the Sultan himself, congratulates you. I am now returning to Istanbul. God willing, you will achieve much more, you will destroy the enemy and you will bless the souls of our martyrs. I leave you to God’s protection. Don’t forget that God is always by our side." (Enver's farewell message to soldiers in Sarıkamış)

Enver, along with his staff, departed Erzurum for Istanbul through Sivas. In Ulukışla's train station, he encountered his uncle, Halil Pasha, imparting the grim news: "The entire force has been lost." Upon reaching Istanbul, Enver Pasha enacted a ban on all publications related to Sarıkamış, citing a patriotic motive to "prevent spies and traitors from demoralising the public through propaganda and lies."

Specific figures detailing Turkish casualties in Sarıkamış remain elusive. The official Turkish Army history posits losses at 60 thousand men, drawing from Russian accounts reporting 7,000 prisoners and 23 thousand Turkish fatalities. This toll includes 10 thousand dead within the XI Corps area and an additional 20 thousand behind the battle lines, succumbing to harsh conditions and illnesses.

The tragedy of Sarıkamış, frequently linked to Enver Pasha's persona today, warrants a closer examination of factors contributing to one of the greatest military disasters of the First World War. Command errors played a pivotal role, yet elements such as severe weather, frost, epidemics, and logistical inadequacies also proved significant. This confluence led to the demise of thousands of Turkish soldiers on mountainous terrain, their fate sealed without firing a single shot.

Enver Pasha's mistakes did indeed contribute significantly to the unfortunate outcome. However, it is important not to solely blame him for the events that unfolded. Rising through the ranks too swiftly deprived him of the field experience necessary for effective leadership. The lack of practical knowledge in commanding armies became evident, leading to a failure in understanding the challenges faced by the soldiers and a neglect of operational necessities. During the period when the Third Army gathered around Erzurum and throughout subsequent operations, soldiers were tasked with covering exceptionally long distances. In the harsh winter conditions, the physical limits of the human body should have been better taken into account. Predictably, units struggled to meet their marching targets, resulting in their dissolution. Executing operations in such extreme conditions necessitates absolute consensus among commanders and soldiers, yet even high-ranking officers lacked a uniform level of determination.

Enver Pasha and Hafız Hakkı, despite their active involvement, faltered in anticipating the difficulties that the army would inevitably face. Balancing the strategic aspects of military operations with the practical challenges encountered on the ground proved elusive. As a consequence, the discord between leaders and soldiers, exacerbated by the arduous winter conditions, proved detrimental to the overall success of the mission. In essence, a more nuanced understanding of Enver Pasha's role unveils a complex web of challenges and misjudgments that contributed to the historical calamity.

The Turkish Army's official historical account arrives at a clear verdict: the pivotal error lay not in the decision to embark on the campaign during winter but rather in the flawed execution. A more meticulously orchestrated assault, aligning with strategic and tactical principles to facilitate coordinated action, held the potential to overcome the Russians even in winter. The linchpin of this success rested on the capabilities of the Turkish soldier. Had the timing been more judicious, even Enver Pasha's plans could have proven apt. Unfortunately, the execution unfolded at an inopportune moment, setting off a chain of subsequent errors. The dysfunctionality of the chain of command emerges as a prominent factor contributing to the ultimate defeat in the Battle of Sarıkamış.

Against Russians in East Anatolia

Hafız Hakkı Pasha, commander of the Third Army, died of typhus on 12 February 1915 and was replaced by Brigadier General Mahmut Kamil Pasha, who inherited an army ravaged by the harsh winter campaign and rampant epidemics. Tasked with restoration, Mahmut Kamil faced the challenge of regaining order. Amidst the desolation, glimmers of hope emerged as reinforcements trickled in from the First and Second Armies. By March 1915, X and XI Corps could once again be deployed, albeit no mightier than a single division. A nascent IX Corps, formed from remnants of artillery and support units, assumed a defensive stance.

In this strategic tableau, stability reigned. The Russian forces, having reached their pre-war border in the north, maintained a poised presence in Turkish towns to the south—Eleşkirt, Ağrı, and Doğubeyazıt. This respite allowed the Turkish Third Army a precious interval for recovery, reorganization, and fortification along fresh defensive lines. Alas, the forces at hand proved insufficient to safeguard the entirety of East Anatolia.

As the weather softened, heralding a change in the tides, the Russian offensive unfurled. 6 May 1915, marked the commencement of their advance through the Tortum Valley toward Erzurum. The valiant Turkish 29th and 30th Divisions halted this incursion, prompting a retaliatory counter-attack by the X Corps in an endeavour to reclaim lost ground. By 13 June, Russian units found themselves retracing their steps to the initial starting line, a testament to the ebb and flow of wartime fortunes.

In the southern expanse of the Caucasian theater of war, Turkish forces faced challenges distinct from those in the north. On 17 May, Russian forces made their presence felt as they entered the town of Van, steadily pushing back Turkish units. Malazgirt had succumbed on 11 May, exacerbating the situation. Supply lines were severed, and Armenian rebellions added to the complexities. The region south of Lake Van lay exposed, demanding the defense of a 600-kilometer stretch by a mere 50,000 men and 130 artillery pieces, leaving the Turks vastly outnumbered by the Russians in this mountainous terrain that proved hard to defend.

Come 19 June 1915, the Russians initiated another offensive, this time towards the northwest, aiming for Lake Van. Russian forces marched from Malazgirt towards Muş, unaware of the Turkish IX Corps' movement, accompanied by the 17th and 28th Divisions. Despite the challenging conditions, the Turks efficiently reorganized, positioning the 1st and 5th Expeditionary Forces to the south of the Russian offensive. A "Right Wing Group" under Brigadier General Abdülkerim Pasha, reporting directly to Enver Pasha, bolstered the defense. The stage was set for the Turkish response to the impending Russian attacks.

The Russian offensive was halted by 16 July, and the IX Corps approached from the northwest, aligning with the fresh forces of the 5th Expeditionary. Together, they pursued the retreating Russians, culminating in the liberation of Malazgirt on 26 July. Though achieved at a significant cost with casualties mounting, this victory proved pivotal for the Turks, boosting morale in the face of adversity.

Following a notable triumph, Abdülkerim Pasha promptly telegraphed Istanbul, seeking approval to persist in the assault. Enver Pasha, brimming with joy, urged Abdülkerim to direct the attack towards Eleşkirt and Karaköse, aiming to expel all Russian elements from the border region.

By 5 August, the Right Wing Group had penetrated 20 kilometres into Russian territory. Nonetheless, the IX Corps' left wing remained exposed due to Abdülkerim Pasha replicating the errors of Sarıkamış—committing all forces to the offensive without maintaining any reserve units. The Russians astutely identified this vulnerability and launched a counterattack. Though the 29th Division rushed to aid, the Turkish offensive formation faced encirclement. Abdülkerim Pasha, left with no alternative, ordered a retreat, resulting in the recapture of Malazgirt by the Russians. Hostilities ceased by 15 August, concluding with 10,000 Turkish soldiers losing their lives and 6,000 becoming Russian prisoners.

While the reorganization of Turkish forces in East Anatolia during spring 1915 marked a significant achievement, the newfound spirit proved futile. The casualties were so extensive that the IX Corps could no longer bolster its strength through reinforcements. The X and XI Corps faced weaknesses. However, the Russians also endured losses. The Caucasian front fell into silence for the remainder of the year as the guns ceased their thunderous echoes.

The Ottoman High Command grappled to replenish the losses suffered by the beleaguered Third Army. The exigencies of the Gallipoli conflict drained precious resources and manpower, leaving the IX, X, and XI Corps without reinforcements. Compounding this, the deployment of the 1st and 5th Expeditionary Forces to Mesopotamia further strained the military apparatus. With the Caucasian front relegated to a secondary status, the once-mighty Third Army stood weakened.

By January 1916, the Third Army's totality stood at 126,000 individuals, a mere 50,539 of whom comprised infantry. Armament included 74,057 rifles, 77 machine guns, and 180 artillery pieces. Facing them was a formidable Russian force of 200,000 men and 380 artillery pieces. The IX, X, and XI Corps adopted defensive postures along the Erzurum road, centred around Köprüköy. The strategic assumption, flawed as it proved to be, rested on the belief that the Russians would abstain from launching an assault.

On 10 January 1916, Russian General Yudenich initiated a sweeping winter offensive, catching the Turkish Third Army off guard. During this critical juncture, Third Army commander Mahmut Kamil Pasha was absent on leave in Istanbul, while Colonel Felix Guse, the chief of staff, recuperated from typhus in Germany. The offensive's initial thrust targeted the XI Corps, breaching Turkish defenses in a mere four days. Subsequently, Turkish units retreated from the Köprüköy lines, and by 18 January, Russian forces encroached upon Hasankale, a pivotal town on the route to Erzurum, establishing a new focal point for the beleaguered Third Army headquarters.

In just one week, the Turkish defensive formation crumbled, resulting in 10,000 casualties and 5,000 taken prisoners. Among the losses were 16 pieces of artillery, while 40,000 men sought refuge within the walls of Erzurum Fortress. The XI Corps suffered particularly heavy losses during this tumultuous period. Meanwhile, the Russians strategized to conquer Erzurum, a robust Turkish stronghold that ranked as the Empire's second most fortified town after Edirne.

Returning from Istanbul on 29 January, Commander of the Third Army, Mahmut Kamil Pasha, sensed the impending Russian assault not only on Erzurum but also a renewed offensive around Lake Van. The fortress faced threats from the north and east, prompting Mahmut Kamil to fortify the defensive lines.

By 11 February, Russian artillery targeted the fortified formations surrounding Erzurum, sparking intense conflict. Turkish battalions, consisting of 350 men, valiantly defended against Russian counterparts numbering 1,000. Despite limited reinforcements, the Russians, in three days, ascended the heights overseeing the Erzurum plain. It became evident to the Third Army command that the town was no longer tenable. Turkish units initiated a retreat from the front's fortified zones, concurrently evacuating the town of Erzurum.

On the crisp morning of 16 February 1916, Russian troops marched into Erzurum. Despite successful Turkish unit withdrawals that skillfully evaded encirclement, the toll of casualties was already staggering. A formidable loss of 327 artillery pieces fell into Russian hands, with support units from the Third Army and approximately 250 wounded souls within the confines of Erzurum's hospital now prisoners of war. Meanwhile, remnants of the valiant X and XI Corps pivoted to establish a new defensive line, eight kilometres east of Erzurum.

Amidst the jubilation lingering from the recent triumph at Gallipoli, Istanbul's revelry abruptly waned with the somber news of the Eastern Front's turmoil and the surrender of Erzurum. Enver Pasha swiftly commanded the deployment of the V Corps, comprising the 10th and 13th Divisions, to reinforce the beleaguered Caucasian front. On 27 February, he replaced Mahmut Kamil Pasha with the seasoned Vehib Pasha, then serving as the commander of the Second Army and renowned hero of Gallipoli. Vehib Pasha, now at the helm, reached Erzincan, the new nerve center of the army, on 16 March. His initial charge: restoring order to the beleaguered Third Army, a force depleted to a mere 25,500 men, armed with 76 machine guns and 86 operational artillery pieces. The fall of Erzurum echoed not just the loss of strategic ground but also the forfeiture of crucial hospitals and logistical support.

Enver Pasha, cognizant of the Third Army's limitations in defending the frontline autonomously, directed the Second Army, then stationed in Thrace under Ahmet İzzet Pasha's command. Their mission: to advance to Diyarbakır in Southeast Anatolia and reinforce the eastern flank held by the Third Army. By August, the Second Army aimed to bolster its strength with four corps and ten divisions.

Meanwhile, the Russians pressed forward with remarkable speed. In March 1916, they disembarked in Rize, a pivotal port in the eastern Black Sea Region, progressing westward to seize Trabzon by 16 April. This development posed a considerable challenge for the Third Army, now isolated from Black Sea reinforcements and supply routes. Compounding these issues, the arrival of the Second Army faced delays due to restricted railroad capacity, with units deployed to Mesopotamia receiving transportation priority.

Facing formidable challenges, Vehib Pasha decided to divide the front in three operational zones: The Southeastern zone, spanning north of Diyarbakır, fell under the command of Mustafa Kemal’s XVI Corps. The Central zone, led by Yusuf Ziya Pasha of X Corps, found support from IX and XI Corps, along with the 2nd Cavalry Division. The Northern zone, situated along the Black Sea coast, was entrusted to Fevzi Pasha’s V Corps.

In the waning days of June, Fevzi Pasha’s V Corps initiated an offensive into the Eastern Black Sea Mountains, aiming to reclaim the port of Trabzon, now utilized by the Russians for maritime reinforcements. Despite achieving minor successes, the primary objective was accomplished through the scarcity of adequate forces. By 28 June, the Turks had advanced ten kilometres towards the sea but were compelled to halt their progress in the face of resolute Russian defense.

Simultaneously, the Russians orchestrated a counteroffensive to alleviate the pressure on Trabzon and pose a threat to the Turkish city of Sivas. Dubbed the Çoruh Campaign, their assault commenced on 2 July. As the Russians approached the outskirts of Bayburt, they confronted the valiant Turkish X Corps. Despite their gallant efforts, the Turks couldn't maintain their ground, and Bayburt fell on 17 July 1916.

Unyielding, the Russians leveraged Bayburt as a bridgehead, launching renewed offensives that breached the Karasu River, forcing the Turkish IX and X Corps into retreat. On 25 July, advanced Russian forces entered the city of Erzincan. With no alternative, Vehib Pasha relinquished the city to the Russians, opting to withdraw westward to impede further Russian encroachment into Anatolia. The Çoruh Campaign persisted for 12 days, witnessing not only the loss of crucial towns but also the sacrifice of 17,000 Turkish lives, with an equivalent number taken as prisoners of war.

After a substantial setback, Ahmet İzzet Pasha, undeterred, opted for an offensive one week following the Russian assault's conclusion. The Second Army's mission was to rescue the imperiled Third Army and reclaim the town of Erzincan. Commencing on 2 August 1916, the Turkish offensive unfolded through three corps-sized groups: III, IV, and XVI Corps. Initially, Mustafa Kemal's XVI Corps successfully seized Bitlis and Muş. However, this triumph failed to secure ultimate victory, as Russian forces bolstered their defenses. Within two weeks of the Turkish offensive, the Russians retaliated with counteroffensives. Concurrently, the Turks grappled with severe supply and logistics challenges. By late September, the Turkish offensive met its conclusion, resulting in some territorial gains but at the heavy toll of around 30,000 casualties.

The remainder of 1916 saw the Turks engage in organizational and operational adjustments on the Caucasian front. Fortunately, the Russians remained quiescent during this period. The harsh winter of 1916-17 rendered combat near-impossible, persisting through the spring. Russia, amidst political and social upheaval, witnessed the chaos of the October Revolution, stalling all military operations and prompting Russian forces to withdraw. Neither Russian soldiers nor the populace harbored the desire to prolong the war. The Turks, facing challenges, couldn't capitalize on this opportunity due to their own unit deficiencies. Pressured by the British in Palestine and Mesopotamia, the Turks withdrew the majority of their forces (five divisions) to the south. Consequently, 1917 transpired without conflict on the Caucasian front. The Russian army gradually disintegrated until it ceased to be an effective military force. The Armistice of Erzincan, inked on 16 December 1917, formally marked the cessation of hostilities.

Recapturing Lost Territories

In the wake of the armistice inked between the Russians and the Turks, the Imperial Russian Army commenced its withdrawal from Anatolian territory. However, the echoes of conflict still resounded. On 4 February 1918, Vehib Pasha, commander of the Ottoman Third Army, corresponded with his Russian counterpart, expressing his intent to launch an offensive. The objective was to thwart Armenian aggression against the Turkish population in territories vacated by the Russian Army.

Informed by a comprehensive report from Lieutenant Hüsamettin, who, having escaped Russian captivity, journeyed to Trabzon, Vehib Pasha gleaned vital intelligence. The remnants of the Russian Army proved incapable of maintaining the frontier line, with British and French representatives aiding in the formation of Armenian and Georgian battalions. Meanwhile, the Armenians, backed by Russian Bolsheviks, harbored plans to expel Muslim Azerbaijanis from the entire southern Caucasus.

Simultaneously, in Istanbul, Enver Pasha crafted his own strategic vision. Seizing the Russian revolution as an opportune moment, he aspired not only to reclaim pre-war frontiers but also territories acquired by the Russians in the 1877-1878 war. This expansion would serve as a launching pad for Turkish dominion in Central Asia. Deployment of reinforcements to the Third Army was ordered, with operations set in motion upon readiness.

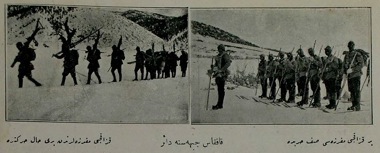

On 5 February 1918, the Turkish offensive commenced, advancing eastward from the line between Tirebolu and Bitlis. A blitzkrieg orchestrated by the Third Army swiftly recaptured lost territories from the Armenians. Kelkit fell on 7 February, Erzincan on 13 February, Bayburt on 19 February, and Tercan on 22 February. Reclaiming the strategic Black Sea port of Trabzon on 25 February, Turkish combat strength burgeoned with the arrival of sea-borne reinforcements.

Armenians fought to keep the city of Erzurum, yet succumbed to liberation by the Turkish I Caucasian Corps on 12 March 1918. Successive victories ensued, with Malazgirt, Hınıs, Oltu, Köprüköy, and Tortum falling in the ensuing two weeks. The tide of history turned, marking significant chapters in the intricate tapestry of war.

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

As the Ottoman Empire sought to reclaim lost territories, peace discussions unfolded between Russia and the Central Powers in Brest-Litovsk (located in present-day Belarus). The treaty, signed on 3 March 1918, mandated the return of specific regions—Ardahan, Kars, and Batumi—acquired by Russia from the Ottoman Empire during the 1877-1878 conflict. However, lacking clarity on the when and how of this restoration, and with these areas already vacated by the Russians, Armenians took control of Kars and Ardahan, while Georgians occupied Batumi.

On 14 March 1918, the Ottoman government initiated negotiations with the representatives of the newly-formed Transcaucasian Federation (Mâvera-yi Kafkas Konfederasyonu) to establish peace conditions in the Caucasus. Insisting on strict adherence to the Brest-Litovsk terms, the Ottoman side faced resistance from Armenian and Georgian delegates who sought concessions, particularly aiming to retain Kars and Batumi. Simultaneously, Turkish forces were advancing towards these contested towns as discussions unfolded in Trabzon.

The talks reached an impasse, prompting Enver Pasha to instruct Vehib Pasha to employ military measures to enforce the Brest-Litovsk terms. Effectively, the army was set to launch an offensive to capture the three cities. Emphasizing Batumi's significance as a gateway to the Caucasus, Persia, and Central Asia, Enver Pasha aimed to first safeguard Muslims in the Caucasus before venturing into Central Asia.

While Enver prioritized the protection of Muslims in the Caucasus, Vehib Pasha, exercising caution, feared that such an operation might unite Armenians and Georgians against local Muslims. Additionally, he doubted the feasibility of securing the region with the available forces, foreseeing potential anarchy. Despite his reservations about Enver's plans, Vehib Pasha had no choice but to proceed with preparations.

In a letter from Istanbul, Enver Pasha asserted, "As the reward for three years of bloodshed and hardship, it is the government's duty to physically reclaim Batumi, Kars, and Ardahan—territories lost by the Ottoman Empire in the past but secured by the Brest-Litovsk treaty."

Vehib Pasha devised a three-pronged offensive plan. The Şevki Pasha Group, comprising the I and II Caucasus Corps and the 5th Infantry Division under Yakup Şevki Pasha's command, would advance towards Kars in the centre. Along the Black Sea coast on the left, the VI Corps would move towards Batumi, while the IV Corps on the right would launch an attack towards Van and Doğubayazıt.

The offensive started (or rather gained momentum, since the troops were already in motion) on 3 April 1918, on which day Ardahan was liberated by the Şevki Pasha Group. In pursuit, the 9th Caucasus Division tracked the retreating Armenian forces to Sarıkamış, the site of a poignant tragedy three years prior, seized on 5 April. Colonel Kazım Bey, at the helm of the I Caucasus Corps, persistently pursued Armenian units. By 8 April, Kağızman stood liberated, marking the commencement of the offensive towards Kars following Yakup Şevki Pasha's directive to Kazım Bey.

The march towards Selim, a town staunchly fortified by the Armenians, saw the 9th and 36th Divisions in action. A temporary halt on 11 April, prompted by news from the ongoing conference in Trabzon, revealed the Transcaucasian Federation representatives ostensibly accepting the evacuation terms of the Brest-Litovsk treaty. Recognizing this as a ruse to buy time, the advance towards Kars resumed the next day. After four days of intense struggle, Selim succumbed on 22 April, paving the way for the next chapter in Kars' fate.

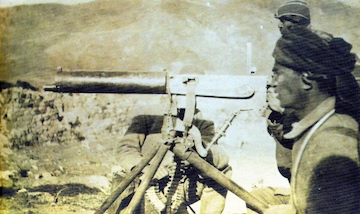

the Russian patrol • Başar Eryöner collection

Back in 1915, following their triumph over the Turks at Sarıkamış, the Russians had strategically fortified Kars. The meticulous fortifications ensured that even if the Turks managed to capture it, victory would prove Pyrrhic. Recognizing this, Kazım Bey opted to lay siege to the town, compelling the Armenians to surrender rather than engaging in a direct capture. The siege commenced on 23 April, orchestrated by the I and II Caucasian Corps.

Swiftly, the Armenian officers acknowledged the inevitable. Facilitated by French intermediaries, General Nazarbekov, stationed in Yerevan, sought a ceasefire. The Turkish response, however, dictated that only the unconditional surrender of the city would suffice. Faced with limited alternatives, the Armenian officers acquiesced to Turkish terms. On 25 April, Cpt. Talat Bey assumed control of the city from General Deyev. Concurrently, the surrounding batteries were seized, and by evening, a regiment from the I Caucasian Corps had taken command of the city. The following day at 10 am, Col. Kazım Bey himself entered as the "Liberator of Kars."

"After 40 years of enslavement, the Fortress of Kars and all those hands were joining back the motherland. I spread the good news and celebrations began everywhere. It was a great joy for me that it was my corps, which had liberated Erzincan and Erzurum in the dead of winter, to have the honor of raising the Turkish flag over Kars. This was my greatest ideal since I was a child." (Col. Kazım Bey in his memoirs)

On the other flanks, it was also going well for the Turks. Traversing the Black Sea coast, the 123rd Regiment from Trabzon reached Çayeli on 2 April, shortly after the 37th Caucasus Division liberated Artvin and Andanuç. The latter's primary target was Batumi, seized after two days of combat on 14 April. Simultaneously, the IV Corps reached Van on 6 April, discovering the grim fate suffered by the local Muslim populace at the hands of Russians. Doğubayazıt was liberated a week later.

While Turkish forces advanced eastward, peace talks resumed on 11 May 1918 in Batumi. Despite negotiations, military operations persisted. Refusal to grant access to Transcaucasian railways against the British in northern Persia led Yakup Şevki Pasha to invade, capturing Gyumri on 15 May and Karakilise on 28 May during continued clashes with Georgians in Akhaltzikhe and Gyumri.

In Batumi, Turkish negotiators, led by Halil Bey, adopted a stern stance. They insisted on the establishment of independent states within the Transcaucasian Federation for all nations, asserting that peace was unattainable otherwise. The Azerbaijanis leaned towards the Ottomans, while Armenians and Georgians, conflicted among themselves, sought to halt the Turkish advance. On 26 May, the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic disbanded, giving rise to three independent states: Democratic Republic of Georgia, Democratic Republic of Armenia, and Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Separate peace treaties were signed between the Ottoman government and each republic on 4 June 1918.

On 5 June, Enver Pasha's meeting with the Germans in Batumi led to heightened tensions due to an incident. Vehib Pasha's troops clashed with a joint Georgian-German unit on the main road to Tbilisi, resulting in the Turks attacking and capturing several prisoners, including Germans.

Army of Islam

In response to German pressure, Enver halted Turkish expansion into Georgia. However, he persisted in his pan-Turkic ambitions. On 8 June 1918, he directed a significant reorganization of Turkish forces in the region. The Third Army gave rise to a new Ninth Army, placed under the command of Yakup Şevki Pasha. Simultaneously, the Eastern Army Group, initially led by Vehib Pasha (later replaced by Halil Pasha), coordinated the actions of the Third and Ninth Armies. Esat Pasha assumed command of the Third Army.

With a northward advance ruled out, Enver shifted his focus east and south, towards Azerbaijan and Persia. By March 1918, he envisioned an "Army of Islam" mobilizing Muslim supporters in the Caucasus, moving through Persia to ensnare British forces in Mesopotamia. On 10 July 1918, this force, comprising the 5th Caucasus Infantry Division, the 15th Division, an independent brigade, and regiment under Nuri Pasha, was activated. The Army of Islam's headquarters stood in Gence, capital of the newly formed Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

The primary objective of this army was to liberate Muslim Azerbaijanis from Armenian and Russian oppression, focusing on the city of Baku. Post the October Revolution, a local Soviet government emerged in Baku, justifying incursions into Azerbaijani territories under the pretext of protecting local Armenians. In reality, their motive was to eliminate the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, preventing the region from breaking away from Soviet Russia. The Baku Soviet relied on a formidable 32-regiment Russian/Armenian joint force for support.

In the wake of confrontations near Baku, the Army of Islam initiated its inaugural assault on the city on 31 July. Shortly before this, a coup d'état had ousted the Bolsheviks in Baku, leading to the establishment of a new government known as the Central Caspian Dictatorship. This government, which enjoyed British support, counted approximately 1,500 British troops among its forces.

The Turkish offensive persisted until 2 August when it was called to a halt. Despite a subsequent attempt on 5 August, this assault also failed to attain its objectives. Faced with a counter-attack from Russian, Armenian, and British forces, the Turkish troops were compelled to retreat westward.

Amidst dwindling morale, the Army of Islam suffered significant losses, reducing the number of combat-ready troops to a mere 3,500. While the troops faced no shortages in food and water, their ammunition supplies were running critically low. In response, Nuri Pasha telegraphed the Third Army headquarters, urgently requesting reinforcements, including 5,000 fresh troops, four batteries, airplanes, 28,000 artillery bullets, 1,500 boxes of rifle bullets, and 20 transportation vehicles. Such support was deemed essential before launching another major offensive against Baku.

A lull settled over Baku for a couple of weeks. Nuri Pasha received the requested reinforcements, with three regiments from the 15th Turkish Division arriving at the Baku front on 9 September. Meanwhile, the Russian, Armenian, and British forces in Baku were occupied with fortifying their defenses. Between 26 August and 1 September, minor Turkish attacks took place, yielding inconclusive results.

During this period, Nuri Pasha meticulously planned a major offensive. Approximately 8,000 Turkish troops and over 6,000 Azerbaijani militia amassed at the city's outskirts, setting the stage for the impending assault by the Army of Islam.

The offensive was launched in the early hours of 14 August 1918, as the 15th Division, under Süleyman İzzet Bey, launched an attack from the north, while the 5th Caucasus Infantry Division, led by Mürsel Pasha, struck from the west. Turkish forces, triumphing in both sectors, left the city's defenders acknowledging the inevitable. Baku surrendered to the Army of Islam at 3:00 pm the following day, marking the end of a futile struggle. After three months of relentless combat, Turkish troops reclaimed Baku, restoring it to its rightful owners, the Azerbaijanis. The liberation of Azerbaijan was fulfilled.

Nuri Pasha, in his report to Enver Pasha, highlighted street clashes between Muslim and Armenian populations during the Battle of Baku. Armenians and a few Russians lost their lives, yet the toll was a fraction of the Muslims massacred in Baku in March 1918.

Another zone of peril for the Muslim populace was Karabakh. Under Col. Cemil Cahit Bey, the 1st Azerbaijan Division secured the Askeran Pass, expelling Armenian forces, ensuring the safety of around 20,000 Azerbaijani Turks in Susha. Azerbaijani General Yusufov assumed command on November 8 as Istanbul contemplated armistice negotiations with the Allied powers, prompting an end to Turkish military operations.

Another place where the Muslim population was under the threat posed by Armenian militia was Karabakh. The 1st Azerbaijan Division was constituted under the command of Colonel Cemil Cahit Bey and became combat ready by 6 October 6. Cemil Cahit Bey led the division for one month expelling Armenian forces from the Askeran Pass leading to the town of Susha and ensuring the safety of around 20,000 Azerbaijani Turks in Susha. Azerbaijani General Yusufov assumed command on 8 November as Istanbul contemplated armistice negotiations with the Allied powers, prompting an end to Turkish military operations.

After the capture of Baku, Nuri Pasha directed his attention to Dagestan, where the Muslim population was being oppressed by the Bolsheviks. The Northern Caucasus Army, comprising the 15th Infantry Division and Dagestani militia, commanded by Yusuf İzzet Pasha, sought to seize Derbent and Petrovsk. The offensive, initiated on 5 October, faced fierce resistance, causing a brief halt. Resuming on 20 October, Derbent fell on 26 October, and Petrovsk succumbed on 8 November, marking the final Turkish offensive of the First World War. The Armistice of Mudros, signed on 30 October 1918, concluded the war for the Turks.

By war's end, the Ottoman Empire, despite setbacks in Palestine and Mesopotamia, reclaimed all territory lost to the Russians in Eastern Anatolia.

![]()

Sources consulted:

- Arslan, O., “Osmanlı’nın Son Zaferleri: 1918 Kafkas Harekatı” (The Last Victories of the Ottoman: The Caucasian Operation 1918), Doğan Kitap, Istanbul, 2010.

- Balcı, R., “Tarihin Sarıkamış Duruşması” (The Sarıkamış Trial of History), Tarih Düşünce Kitapları, Istanbul, 2004.

- Balcı, R., “Sarıkamış Yolun Sonu” (Sarıkamış The End of the Road), Babıali Kültür Yayıncılığı, Istanbul, 2006.

- Bardakçı, M. (ed.), “Hafız Hakkı Paşa’nın Sarıkamış Günlüğü” (Hafız Hakkı Paşa’s Sarıkamış Diaries), Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, Istanbul, 2009.

- Baytın, A., “Sessiz Ölüm: Sarıkamış Günlüğü” (Silent Death: Sarıkamış Diary), Yeditepe Yayınları, Istanbul, 2007 (edited by Dervişoğlu, İ. from the original text first published in 1944).

- Celalettin Efendi, “Bir Teğmenin Doğu Cephesi Günlüğü” (East Front Diary of a Lieutenant), Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, Istanbul, 2009 (prepared by İstekli, B.).

- Çakmak, F., “Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nda Doğu Cephesi: 1935 Yılında Harp Akademisinde Verilen Konferanslar” (The Eastern Front in the First World War: Conferences Delivered at the War Academy in 1935), Genelkurmay Yayınları, Ankara, 2005.

- Eren, Ö., “Sarıkamış’a Giden Yol” (The Road to Sarıkamış), Alfa Yayınları, Istanbul, 2005.

- Eti, A.R., “Bir Onbaşının Doğu Cephesi Günlüğü 1914-1915” (East Front Diary of a Corporal 1914-1915), Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, Istanbul, 2009.

- Görüryılmaz, M., “Türk Kafkas İslam Ordusu ve Ermeniler” (Turkish Caucasian Islam Army and the Armenians), Bilgeoğuz Yayınları, Istanbul, 2007.

- İlden, Ş., “Sarıkamış”, İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, Istanbul, 2000.

- Larcher, M., “Kafkas Harekatı” (The Caucasus Operation), Omia Yayınları, Istanbul, 2010 (partial translation of the original work in French “La Guerre Turque dans la Guerre Mondiale” published in 1926, translation by Kapyalı, C.).

- Müderrisoğlu, A., “Sarıkamış Dramı” (Tragedy of Sarıkamış), Kastaş Yayınları, Istanbul, 1997.

- Öğün, T., “Kafkas Cephesinin Birinci Dünya Savaşı’ndaki Lojistik Desteği” (Logistics Support of the Caucasian Front During the First World War), Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi, Ankara, 1999.

- Reynolds, M.A., “Shattering Empires: The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires 1908-1918”, University Press, Cambridge, 2011.

- Serhadoğlu, M.R., “Savaşçı Doktorun İzinde” (Following the Footsteps of the Warrior Doctor), Remzi Kitabevi, Istanbul, 2005 (based on the memoirs of Şehidullah Fikri Bey).

- Sönmez, B. and Yıldız, R., “Ateşe Dönen Dünya: Sarıkamış” (The World that Turns into Fire),Ikarus Yayınları, Istanbul, 2008.

- Taşyürek, M., “Sarıkamış: Bir Hüznün Tarihi” (Sarıkamış: The Story of a Grief), Yitik Hazine Yayınları, Istanbul, 2006.

- Tekir, S., “Beyaz Harp” (The White War), Kronik Kitap, Istanbul, 2021.

- Tokad, M.F., “Kibrit Kutusundaki Sarıkamış-Sibirya Günlükleri” (Sarıkamış-Siberia Diaries inside a Match Box), Timaş Yayınları, Istanbul, 2010.

- Tonguç, F., “Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nda Bir Yedek Subayın Anıları” (Memoirs of a Reserve Officer in the First World War), İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, Istanbul, 2006. (first published in 1960)

- Yergök, Z., “Sarıkamış’tan Esarete” (From Sarıkamış to Slavery), Remzi Kitabevi, Istanbul, 2005 (prepared by Önal, S.).

- Yüceer, N., “Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nda Osmanlı Ordusu’nun Azerbaycan ve Dağıstan Harekatı” (Azerbaijan and Dagestan Operations of the Ottoman Army in the First World War), Genelkurmay Yayınları, Ankara, 1996.

- Official History, “Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nda Türk Harbi – Kafkas Cephesi 3. Ordu Harekatı” (Turkish Battles in the First World War – Third Army Operations at the Caucasian Front), Genelkurmay Yayınları, Ankara, 1993.

PAGE LAST UPDATED ON 7 JANUARY 2024