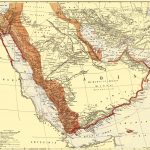

Arabia existed as a constituent part of the Ottoman Empire from the 16th century onwards, yet the Sublime Porte never attained complete sovereignty over the peninsula. Nomadic Arab tribes, eschewing allegiance to the distant ruler in Istanbul, not only resisted imperial authority but also engaged in raids on imperial property and frequently rebelled against Ottoman governors. Istanbul, lacking the military prowess to dissuade Arab incursions and suppress rebellions, crucially failed to establish the requisite socio-economic conditions for the local populace to transition from a nomadic to a settled lifestyle.

Uprisings burgeoned, particularly in mountainous strongholds and regions beyond the government's immediate control in Istanbul. The government's primary recourse for a considerable period was making financial concessions to specific tribes, aiming to dissuade them from taking up arms and, notably, preventing them from assaulting pilgrims en route to Mecca.

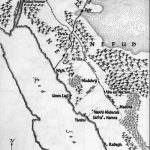

In 1910 and 1911, the Arabian Peninsula stood alongside Syria, a tumultuous epicenter within the vast expanse of the Ottoman Empire. Local uprisings in Syria were kindled by government policies perceived as encroachments on the privileges of regional leaders. Conversely, in the Arabian Peninsula, the impetus for Arab leaders lay in staunch resistance against the centralizing measures of the government. These measures included intrusive initiatives like census registration, taxation, and the Hejaz Railway, which had linked Damascus to Medina since 1908. As the unrest gathered momentum, the Sublime Porte deemed it imperative to adopt a resolute stance regarding the unfolding events in this segment of the Empire.

Amidst the scorching summer of 1910, a band of Druzes, inhabitants of the East Jordan region, initiated raids on Ottoman settlements. Responding to this turmoil, Istanbul dispatched a formidable force led by Faruk Sami Pasha to quell the Druze uprising. Once the turbulent echoes of this insurrection were quashed, Faruk Sami's forces shifted their focus to Transjordania, where Bedouin rebels posed a new challenge. Concluding this expedition, the government redirected its efforts towards bolstering socio-economic conditions in the region, investing in its upliftment.

In the southern realms of Asir and Najd, where the Saud family held sway, a different tale unfolded. The year 1910 witnessed the Sublime Porte fortifying its military presence and bolstering governance in these lands. Here, the authorities relied on the allegiance of notable locals like Ibn Rashid of Najd and Sharif Hussein of Mecca, who staunchly opposed the Sauds.

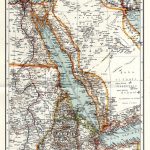

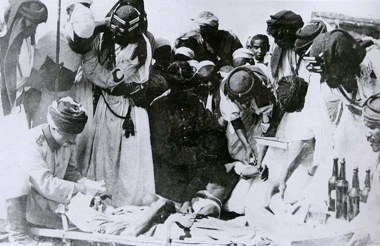

Meanwhile, in the distant land of Yemen, where the Empire's grip was fragile, Imam Yahya, the hereditary ruler enjoying Shiite support, had risen in rebellion. In 1910, he proclaimed a holy war against the Ottoman Empire. Responding swiftly, a formidable force led by Ahmet İzzet Pasha was dispatched. According to the recollections of Major İsmet Bey, later known as İsmet İnönü, Ahmet İzzet Pasha secured the backing of local sheiks and launched an offensive against the insurgents. Within a mere ten days, San'a was reached, but the arduous task of cleansing Yemen extended over several months. İsmet Bey noted that, contrary to expectations, the primary adversary of the Ottoman forces wasn't Imam Yahya but a cholera outbreak.

After a series of clashes in 1911, the warring factions opted for peace. The agreement allowed Imam Yahya to maintain autonomy, safeguard his religious and political influence, and receive financial concessions. In return, the agreement stipulated that no gunfire would echo through the valleys of Yemen.

Hejaz and the Holy Places

In the heart of the Arabian Peninsula, Hejaz held a singular distinction, cradling the sanctuaries of Islam, the revered cities of Mecca and Medina. Since the epoch of the Abbasids, the preeminent figure in this realm was the Sharif of Mecca, the venerable leader of the Hashim clan, guardians of Prophet Mohammad's lineage and custodians of the sacred cities. In the wake of the Ottoman Sultan Selim II's conquest of Syria and Egypt in 1517, the Sharif of Mecca acknowledged the Ottoman caliph's supremacy, yet retained a substantial measure of local autonomy. Though Hejaz fell under Ottoman governance, the de facto rulers remained the Hashemite grand sharifs.

Fast-forward to November 1908, a pivotal moment when Istanbul appointed Sayyid Hussein Bin Ali as the new Sharif of Mecca. Upon assuming office, Sharif Hussein forged alliances with Ottoman authorities, both military and civilian, engaging in campaigns against uprisings in the peninsula. His adversaries included rebels such as Ibn Saud and Idrisi of Asir, threats not only to the Empire but also to Hussein's pursuit of dominance in the Arabian expanse. Driven by a desire to demonstrate unwavering allegiance to the Sultan and the Sublime Porte, Sharif Hussein walked a delicate balance. Simultaneously, he harboured reservations about the centralization endeavours and reforms undertaken by the government, perceiving them as encroachments upon his unassailable local authority.

As the specter of war loomed on the horizon, Istanbul, its power consolidated under the Committee of Union and Progress government, strategically nurtured relations with Arab tribes. The city sought the invaluable assistance of Sharif Hussein, recognising his pivotal role in restoring order to the tumultuous region and capturing the affections of the Arab populace. By 1914, dissent among the Arabs had either been quelled, set aside, or banished to the fringes. Yet, Istanbul's pursuit of influence over the Arab world was not unchallenged; a formidable adversary awaited in the form of Britain.

The year 1914 witnessed a heightening rivalry between Istanbul and London as they vied for the loyalty of Arab tribes. Rumours circulated of an Arab alliance coalescing under the banner of an Arab caliph, adding intrigue to an already complex geopolitical landscape. Concurrently, Sharif Abdullah, son of Hussein, engaged in diplomatic exchanges with British authorities in Egypt. This backdrop framed the Ottoman government's decision, in January 1914, to appoint Colonel Vehib Bey to the dual role of governor and armed forces commander in Hejaz—a move designed to assert Istanbul's claim over the territory and serve as a pointed reminder to Hussein.

The stage was set for a delicate dance of diplomacy and power plays, where allegiances hung in the balance, and the fate of nations intertwined. The unfolding drama between Istanbul and London would cast its shadow over the shifting sands of history, leaving an indelible mark on the destiny of the Arab world.

As soon as he was in Medina, Vehib Bey found himself entwined in a fierce clash with Sharif Hussein, their visions diverging on priorities and jurisdiction. Istanbul, however, had not sought such discord. While Hussein remained a valuable ally, a need to rein him in became paramount. Vehib Bey diligently dispatched reports to Istanbul, urging the dismissal of Sharif Hussein, citing his alleged desire for the state's downfall and his unwavering readiness to collaborate with the enemy in the face of a hostile attack on the Red Sea coast.

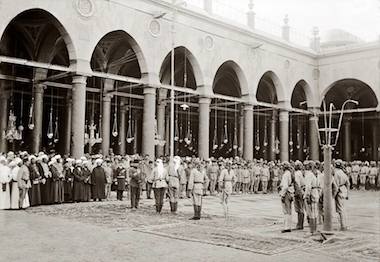

As the Ottoman Empire, under the reign of Sultan Mehmet Reşad, entered the theatre of war, a pivotal decree echoed across the realm. The Sultan, also holding the esteemed position of Caliph for all Muslims globally, proclaimed a "jihad," a sacred war against the Triple Entente. Since 1913, the government had woven threads of Islamic persuasion in the Arab provinces, and with the call for jihad, all Muslims were summoned to join forces with the Sultan's troops. This jihad didn't set out to pit the world's Muslims against Christian powers, for the Ottoman Empire itself stood allied with two Christian nations, Germany and Austria-Hungary. Instead, its purpose was to boost domestic support for the government's war efforts and impede the Entente's mobilization campaign, while at the same time the Entente's campaign encompassed British endeavours to augment influence over Arab tribes, motivating them to turn against the Ottoman Empire.

In the sacred precincts of Mecca, Sharif Hussein bestowed his blessing upon the jihad. However, lingering doubts clouded his decision on whether to actively partake in the holy war or align himself with British interests. Engaging in what was truly a waiting game, Hussein adeptly maintained ties with both factions, navigating the treacherous waters of uncertainty.

Cemal Pasha Arrives

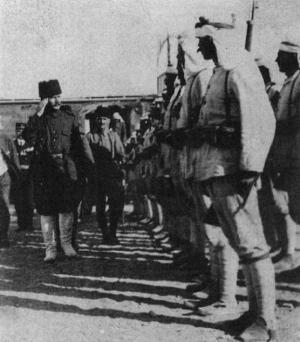

In December 1914, Cemal Pasha assumed command of the Fourth Army in Damascus, embarking on preparations for his expedition to the Suez Canal. He beckoned Hussein to join, entrusting him with the leadership of his Bedouin forces. Hesitant, Hussein refrained from full commitment but pledged to dispatch units under the command of his son, Sharif Ali.

As February 1915 unfolded, Cemal advanced towards Suez, drawing the bulk of Ottoman forces from Hejaz. Meanwhile, Hussein assured Enver Pasha that he would safeguard the Caliph's interests in holy places, on the condition that assaults on his own position were not tolerated. Vehib Bey, the perceived instigator of such attacks according to Hussein, had already been appointed as the commander of the Third Army in the Caucasus, departing from Hejaz.

The Suez Canal expedition under Cemal concluded in disappointment. Upon his return to Damascus in May 1915, emergency powers were granted to him. Unveiling "evidence" of dissent among Arab opponents in the closed French consulates in Beirut and Damascus, Cemal initiated prosecutions against Arab cultural and political leaders. A Maronite priest, known for his Francophile leanings, faced public execution for treason against the Empire. Subsequently, eleven Beiruti leaders were tried at the military court in Aleyh, meeting their end on 21 August 1915, hanged in the town square.

In the shadowy corridors of history, Cemal Pasha unleashed a reign of terror, relentlessly exacting reprisals upon his Arab adversaries. As May 1915 drew to a close, Sharif Faisal, scion of Hussein, approached Cemal Pasha, declaring his family's readiness to champion the Ottoman cause. The echoes of loyalty resonated again on the 10 July when Hussein himself assured Cemal Pasha of his unwavering commitment. Simultaneously, Hussein engaged in clandestine dealings with Enver, who, in gratitude, tasked him with the formation of an Islamic Society. In the clandestine dance of power, Enver bestowed funds and arms upon the Sharif to weave the intricate tapestry of Islamic influence across the region.

Yet, merely four days after pledging allegiance to the jihad, Sharif Hussein surreptitiously corresponded with Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt. McMahon harboured intentions to undermine the Ottoman war machine by orchestrating a new front at its vulnerable rear. This covert exchange, veiled in secrecy, persisted until January 1916, ultimately birthing an unexpected alliance between Sharif Hussein and the British against the Ottoman Empire.

However, the Ottomans were not entirely oblivious to the machinations of Hussein. Basri Pasha, the Ottoman governor in Medina, dispatched reports, expressing suspicion towards Sharif Ali's involvement in anti-Ottoman propaganda among the tribes. He perceived the goodwill exhibited by the Sharifs as a mere façade, concealing a strategy to buy time. Similarly, Cemal Pasha harboured mistrust, foreseeing the potential betrayal in Hejaz. To safeguard against this perceived threat, he deployed Fahreddin Pasha, commander of the XII Corps, to Medina. The stage was set, and the intricate dance of allegiances and betrayals unfolded against the backdrop of the shifting sands of Turkish history.

"According to an article in Temps newspaper, Sharif Hussein had made a deal with the British as early as 1 January 1916 and he waiting for an opportunity to declare his revolt. At that time, if I had been aware of the situation, I would immediately have Sharif Faisal arrested in Damascus and Sharif Ali arrested in Medina. I would even send a Turkish division to Mecca to detain Sharif Hussein and his other sons. In that way I could have suppressed this cursed rebellion before it even broke out. However, I had no concrete evidence whatsoever to prove the wrongdoings of these traitors." (Cemal Pasha in his memoirs)

The Arab Revolt

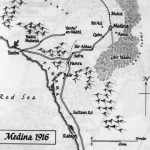

In May 1916, Cemal Pasha discerned Hussein's intentions clearly. He promptly cabled Basri Pasha and Fahreddin Pasha, instructing them to assume defensive positions, fortify the railway outposts, and refrain from initiating conflict. By 22 May, reinforcements set forth from Syria towards Medina.

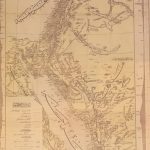

On the night of 23/24 May, the Arab Revolt commenced as rebels, prompted by Hussein, attacked Ottoman outposts encircling Medina. Subsequently, the rebels extended their reach, shelling the city of Jiddah. British naval artillery in the Red Sea lent support to the rebels' cause. Jiddah, defended by Ottoman garrisons comprising two infantry regiments and a mountain battery, withstood the assault for a week before succumbing to the relentless pressure.

In the quiet embrace of Medina, Ottoman reinforcements materialized on the last day of May, marking the genesis of the Hejaz Expeditionary Force, entrusted to the capable command of Fahreddin Pasha. This force, birthed to confront Hussein's legion, a formidable assembly of some 50,000 men, armed with a meagre 10,000 rifles. Predominantly composed of the hardy nomads of the Arabian deserts, the denizens of urban bastions like Mecca, Taif, and Jiddah, exhibited scant enthusiasm for Hussein's cause. Support for the revolt was confined to Hejaz and certain nearby tribal regions. Hussein's adherents comprised a small number of tribesmen, their expenses covered by the British treasury, and a few officers from outside Hejaz—either Allied prisoners of war or expatriates dwelling in territories under British control.

Notwithstanding such odds, the Arabs, under Hussein's leadership, persisted in their military successes. By the waning days of September 1916, the rebels had seized control of the coastal cities of Rabegh, Yenbo, and Qunfida.

Faced with the relentless victories of Hussein's forces, the Ottoman government opted for a dual-fronted approach. On the propaganda battleground, an earnest campaign unfolded across Arab provinces to undermine Hussein's credibility. To orchestrate this stratagem, Sharif Haydar ascended as the new and legitimate Emir of Mecca, officially assuming office in Medina come August 1916.

In the realm of military strategy, the Turks orchestrated a shift from defensive manoeuvres to an offensive thrust, eyeing the capture of Mecca—then under the control of Hussein’s forces. On 14 September 1916, Enver Pasha and Cemal Pasha convened in Syria to deliberate on this crucial matter. The pressing need for reinforcements in Palestine to counter the advancing British prompted a recalibration of plans; the intended assault on Mecca was abandoned in favour of adopting a defensive posture centred on Medina.

Deterioration loomed on both the Palestinian and Hejazi fronts. Backing the Arab rebels, the British dispatched an officer in October 1916, aligning their efforts. Captain T.E. Lawrence, the designated liaison, skillfully leveraged British naval support to repel the Ottoman assault on Yenbo in December 1916. Persuading Arab leaders, namely Hussein’s sons Faisal and Abdullah, Lawrence urged a coordinated approach, redirecting focus from Medina to the vulnerable Hejaz Railway. The turning point came on 3 January 1917, as Faisal’s forces initiated a northward push along the Red Sea coast towards Wejh. Succumbing after a mere two days, the Ottoman garrison retreated towards Medina, yielding ground in the face of strategic realignment.

In the early months of 1917, the winds of change swept across the Arabian Peninsula, tilting the scales in favour of the Arab rebels. Their numerical superiority was matched only by the efficiency of their logistics, ensuring a steady flow of sustenance across the arid landscape. Meanwhile, the Turks found themselves compelled to retreat, adopting a defensive stance in the ancient city of Medina, with scattered detachments tracing the path of the Hejaz Railway. The situation was dire, prompting Enver Pasha and Cemal Pasha to make a strategic decision – a withdrawal from Hejaz, focusing their efforts on the contested lands of Palestine.

Yet, the emotional weight of abandoning the sacred cities of Islam, steadfast under Ottoman rule for nearly four centuries, hung heavily in the air. Sultan Mehmet Reşad, supported by the counsel of Talat Pasha and Fahreddin Pasha, engaged in persuasive discourse with Enver and Cemal. Eventually, a resolution emerged – a resolute commitment to stand firm in Hejaz, with Medina as the bastion to be defended at any cost. Only the infirm and injured were deemed fit for departure, entrusted with the sacred relics of Islam on their journey to Istanbul. The rest of the army remained steadfast, prepared to confront the challenges that lay ahead.

One notable departure, prompted by security concerns, was that of the Emir of Mecca, Sharif Haydar, who chose to vacate Medina on 14 March, 1917. The tides of history continued to surge, carrying the weight of decisions made in the unforgiving landscapes of the Arabian Peninsula.

Defending Medina

Medina was under siege. Sharif Abdullah's headquarters strategically positioned nearby, obstructing crucial supply routes to the city, leaving the Turks devoid of reinforcements. Turkish forces, holding both the city and the railway stations, faced relentless assaults from Arab camel cavalry, backed by the British, who dealt blows to Turkish positions. Lawrence played a pivotal role, not only offering strategic support to the Arabs but also engaging with tribes outside the revolt, enticing them to join by compensating in gold.

On 12 July 1917, Aqaba, the last Ottoman port on the Red Sea, succumbed to Arab forces, facilitating the inflow of British supplies. Post Aqaba's fall, Lawrence journeyed to Cairo, meeting General Allenby, orchestrating Arab rebel collaboration with British forces in northern Palestine. This marked a pivotal shift in the war's trajectory; Hejaz and Palestine united, propelling the Arab Revolt towards Syria.

In the Arabian Peninsula, Medina remained defended by a dwindling Turkish force led by Fahreddin Pasha. Cut off from supplies and reinforcements, Fahreddin Pasha, in a cable dated 7 March 1918 to Mustafa Kemal Pasha, then commander of the Yıldırım Group of Armies, lamented their dire situation. With a meager provision of 2,000 calories per day per soldier, underfed animals, and a daily toll of five camels and horses perishing, the situation deteriorated. Despite requiring 16 tons of daily supplies, they possessed less than half. Pleading for aid, Fahreddin urged Mustafa Kemal, "Please, do not let Medina fall just because of hunger."

“We were not concerned about those bandits and their cooperators who were surrounding us. What we were affected by was the difficulty in finding bread. In those sacred lands, there were plenty of dates growing, but that was all. Nothing else to feed ourselves with. But suddenly we saw that blessings were pouring down from the sky!” What this officer saw as blessing was grasshoppers. Having no option left, Fahreddin Pasha had to order his men to eat grasshoppers. In a decree he issued, he stated that grasshoppers contain nutrition and they taste like birds. He even provided guidelines on how to cook grasshoppers: Boil them. Take away the heads and legs. Mix them with rice. Serve with lemon and olive oil. Such were the living conditions of the Turkish troops who remained in Medina to defend the holy city of Islam." (Memoirs of Feridun Bey, an officer who was in Medina at the time)

The Turkish forces persisted in their struggle, engaging in ongoing skirmishes with Arab rebels amidst the desert encompassing Medina. Although assistance was beyond reach, Istanbul remained cognizant of the unfolding events.

"With what hope did you undertake the defense of Medina? At that time we could find no reason other than your adherence to Islam… Everybody was desperate, everybody was hopeless about Medina. It was only you, who were happy and smiling. Today the fronts are far from being enjoyable. Medina had to be evacuated and every single remaining soldier had to be sent to Gaza. You were not happy about this: Don’t let me take down the banner raised by Sultan Selim with my own hand. How many soldiers can you sacrifice for Medina, one thousand, three thousand? Give me what you can and I will not let a single foreigner, that’s what you said. But they withdrew all the forces. What is left to you was a handful of heroes. Today you are defending our sacred city with these heroes, who are already sacrificed." (Falih Rıfkı Bey, who had also served in Syria as an officer in Cemal Pasha’s Fourth Army, in his article in the newspaper Akşam, 30 November 1918)

Fahreddin Pasha and his men stood as unwavering guardians of Medina, prepared to defend it at any cost. Yet, the tides of fate turned on 31 October 1918, when a cable from Chief of Staff Ahmet İzzet Pasha reached all Ottoman garrisons, bearing news of a momentous accord with the Entente powers: “We signed an agreement with the Entente powers to be effective as of today, October 31, 1918, afternoon. Representatives of the mentioned states informed their armies in Bulgaria, Syria and Iraq about this issue. Conditions of the agreement must be strictly adhered to and the receipt of this correspondence must be confirmed. Details to be provided later.”

This cable was followed on November 6, by a cable sent by Ahmet İzzet Pasha directly to Fahreddin Pasha: “After having done all kinds of sacrifices for religion and honour for four years, the fact that our alliance lost the war forced the Ottoman state to sign an armistice with the Entente. According to one of the clauses of the armistice, Ottoman units and garrisons in Hejaz, Asir and Yemen have to surrender to the nearest Entente commander. It is certainly acknowledged that for you, my comrades in arms who have been executing their duty of honour for years, agreeing with such a terrible condition can only result from the patriotic feeling of saving the motherland from definitive death. I am sure that you will crown your sacrifices, which are appreciated even by our enemies, by fully complying with this heavy task.”

Fahreddin Pasha stood resolute, unwilling to forsake Medina. Despite the government's repeated directives, he skillfully evaded a definitive response, buying time. The Minister of War, Cevat Pasha, dispatched the order twice, first via cable on 28 November, and then, on 8 December, delivered in person by Captain Ziya Bey.

A pivotal gathering occurred on 27 December when Fahreddin Pasha convened his entire staff. Divisions emerged within the camp—some officers unwaveringly committed to following Fahreddin Pasha and holding their ground in Medina. Conversely, a faction, spearheaded by Lieutenant Colonel Emin Bey, viewed resistance as futile. They leaned towards complying with the government's directives to minimize potential losses, yet consensus eluded them.

The schism persisted until 5 January 1919, when Colonel Ali Necip Bey, commanding the 58th Division, sought an audience with Fahreddin Pasha. With an air of finality, Ali Necip Bey acknowledged Fahreddin Pasha's authority over the surrender decision. He conveyed the officers' unanimous resolve to abide by Fahreddin Pasha's orders, albeit expressing a collective inability to discern an alternative to surrender. Following extensive deliberations, Fahreddin Pasha reluctantly acceded.

On 7 January 1919, over two months post-armistice, the envoys of Turkish, Arab, and British forces inked an accord detailing the "Evacuation of Medina and the Withdrawal of Ottoman Forces to Coastal Regions and Their Homelands." Just three days later, on 10 January, Fahreddin Pasha bid farewell to Medina, concluding his visit to the sacred Islamic sites. Although a desire lingered for a prolonged stay, the efficacy of the agreement hinged on his departure. It fell upon his officers to forcibly apprehend the formidable "Desert Tiger" and deliver him into the hands of the British.

“At that moment, those who were begging him looked at each other realizing that the time has come to execute a decision that was already made. Suddenly they seized they surrounded the Pasha and, without being able to stop the tears falling from their eyes, they seized him… Facing this collective act of his closest commanders, Fahreddin Pasha had nothing left to do but to succumb to his fate in deep sorrow.” (Feridun Bey in his memoirs)

In the arid landscapes of Medina, an epochal moment unfolded on the day-month-format when the Turkish forces, with a heavy heart, surrendered to the relentless march of fate. The stark tally: 654 officers, 6,000 men, 30,000 rifles, 75 machine guns, and 22 artillery pieces, diverse in their formidable sizes. Fahreddin Pasha, a stoic figure among them, alongside his officers and the remaining Turkish troops, found themselves bound for prisoner camps in Cairo, a poignant violation of the armistice inked with Arabs and the British.

After the war, Cemal Pasha, in the reflective pages of his memoirs, cast a somber light on the Arab Revolt. His words etched a narrative of disaster for the Arab world, condemning Sharif Hussein as a traitor to the very fabric of Arab and Muslim identity. This sentiment echoed in the annals of history, asserting that Hussein was no liberator, but an imperialist opportunist, yearning to forge his own dominion upon the shards of the Ottoman legacy.

In the tapestry of Turkish memory, the Arab Revolt remains vivid, a chapter often narrated with a bitter refrain – "the Arabs have stabbed us in the back." Yet, caution must temper these sentiments, for the chasm between historical perceptions and raw truths looms large. It is prudent to recall that none of the Arab units within the Ottoman Army defected to Sharif Hussein's cause. Neither did any prominent Arab political or military figure pledge allegiance to his banners. The majority of Arabs clung to the ideological bedrock of the Ottoman Empire, their loyalty unfaltering, anchored in the name of Islam.

![]()

Sources consulted:

- Barr, J., “Setting the Desert on Fire: T.E. Lawrence and Britain’s Secret War in Arabia”, Bloomsbury, London, 2007.

- Er-Reis, R.N., “Osmanlıların Çöküş Döneminde Arap Casusları” (Arab Spies during the Period of Ottoman Decline), Selenge Yayınları, Istanbul, 2006 (translated by Batur, D.A. from the Arabic original).

- Fromkin, D., “A Peace to End All Peace”, Owl Books, New York, 2001. (first published in 1989)

- Kabacalı, A., “Arap Çöllerinde Türkler” (Turks in Arabian Deserts), Cem Yayınevi, Istanbul, 2003.

- Kandemir, F., “Fahreddin Paşa’nin Medine Müdafaası” (Fahreddin Paşa’s Defence of Medina), Yağmur Yayınları, Istanbul, 2006 (first published in 1971).

- Kıcıman, N.K., “Medine Müdafaası: Hicaz Bizden Nasıl Ayrıldı” (Defence of Medina: How We Lost Hejaz), Sebil Yayınevi, Istanbul, 1971.

- King Abdullah el-Hussein of Jordan, “Biz Osmanlı’ya Neden İsyan Ettik?” (Why We Rebelled Against the Ottomans), Klasik Yayınları, Istanbul, 2006 (translated by Özkan. H. from the Arabic original).

- Kolaoğlu, O., “Lawrence Efsanesi” (The Legend of Lawrence), Yeditepe Yayınevi, Istanbul, 2016.

- Kuşçubaşı, E., “Turkish Battle at Khaybar”, Arba Yayınları, Arba Yayınları, Istanbul, 1997 (translated/edited by Stoddard, P.H. and Danışman H.B.).

- Lawrence, T.E., “Seven Pillars of Wisdom”, Wordsworth Editions, London, 1997. (first published in 1935)

- Özyüksel, M., “Hicaz Demiryolu” (Hejaz Railway), Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, Istanbul, 2000.

- Polat, Ü.G., “Türk-Arap İlişkileri: Eski Eyaletler Yeni Komşulara Dönüşürken” (Turkish-Arab Relations: As Old Provinces Turned into New Neighbours”, Kronik Kitap, Istanbul, 2019.

- Uğurlu, Ö.A., “Yemen: Savaşanlar Anlatıyor” (Yemen: As Told by Those Who Fought), Örgün Yayınevi, Istanbul, 2007.

- Official History, “Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nda Türk Harbi – Hicaz, Asir, Yemen Cepheleri ve Libya Harekatı” (Turkish Battles in the First World War – Hijaz, Asir, Yemen Fronts and Operations in Libya), Genelkurmay Yayınları, Ankara, 1978.

PAGE LAST UPDATED ON 4 JANUARY 2024