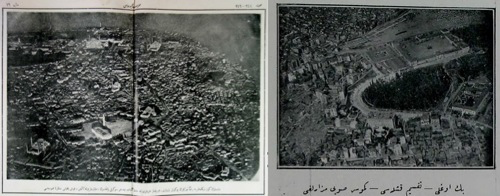

Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, represented a coveted objective for the aircraft of the Allied forces. Its strategic significance emanated not only from housing the headquarters of the Ottoman High Command and vital military installations but also from hosting pivotal industrial, commercial, and social targets. Recognizing the looming threat posed by enemy aircraft, the High Command implemented a series of directives in March 1916. These measures encompassed the fortification of the city with anti-aircraft artillery, the establishment of an early warning system, and the implementation of various civil defense protocols.

Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, represented a coveted objective for the aircraft of the Allied forces. Its strategic significance emanated not only from housing the headquarters of the Ottoman High Command and vital military installations but also from hosting pivotal industrial, commercial, and social targets. Recognizing the looming threat posed by enemy aircraft, the High Command implemented a series of directives in March 1916. These measures encompassed the fortification of the city with anti-aircraft artillery, the establishment of an early warning system, and the implementation of various civil defense protocols.

The inaugural air raid on Istanbul unfolded on 12 April 1916, when two British aircraft, departing from the island of Imbros in the Aegean Sea, released a total of 11 incendiary devices on the munitions plant in Zeytinburnu and the aircraft hangars in Yeşilköy. Concurrently, propaganda leaflets were disseminated over the city itself. Despite its modest armament capacity, this initial squadron's objective did not seem to be inflicting damage upon the city but rather conveying the message that Istanbul was not impervious.

In the aftermath of this initial assault, Istanbul's vulnerability became apparent. Subsequently, the Ottoman High Command promulgated a second set of directives for the protection of the imperial capital. This decree posited that air raids were likely to originate from either the Black Sea or the Aegean Sea and stipulated the following measures:

- Vigilant monitoring of Saros and Edremit bays for approaching enemy vessels, considering the potential launching points from both Aegean islands and battleships.

- Deployment of aircraft observation posts, interconnected with Turkish air units via phone or telegram lines, along conceivable routes of enemy aircraft.

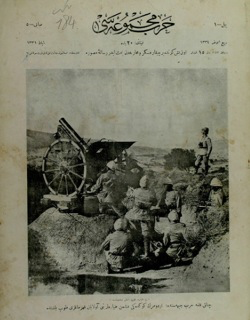

- Positioning of anti-aircraft batteries at strategic locations including Kağıthane, Zeytinburnu, Yeşilköy, Okmeydanı, Osmaniye, Sarayburnu, İstinye, Tophane, Başıbüyük, and Baruthane.

- Mandating the blackout of all city lights during air raids.

These measures effectively thwarted subsequent enemy attacks in the ensuing months. However, the air raids underscored a notable deficiency in informing civilians about proper procedures during such events.

In early 1917, the escalating threat against Istanbul became evident. By March of that year, vessels of the Russian fleet had positioned themselves near the northern entrance of the Bosphorus. On 26 March, three aircraft launched from the Russian ships engaged in a dogfight with Turkish planes, resulting in the downing of one aircraft. A similar raid occurred on 4 April when Russian planes bombed the Bosphorus entrance and the village of Kilyos before encountering resistance from Turkish aircraft.

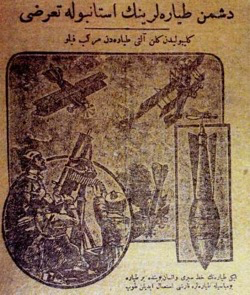

Despite these actions, it became apparent that the Russians could not extend their reach to the city itself. However, the Turks soon discerned that British aircraft posed a more significant threat. On the night of 9 July 1917, two British planes approached Istanbul from the west, traversing Çanakkale and Şarköy. Their objectives encompassed sinking the warship Yavuz, destroying the aircraft hangars at Yeşilköy, and causing damage to the Ministry of War building in the city center.

One of the planes reached İstinye and dropped four bombs on the warships anchored at the bay. Although missing Yavuz, Numune-i Hamiyyet and Yadigar-ı Millet suffered hits. The former succumbed within 45 minutes, resulting in the loss of 30 sailors and injuries to 10 others. The latter sustained minor damages. Simultaneously, the second plane dropped its bombs on the Ministry of War. One bomb struck a stable in the front yard of the Ministry building, inflicting minimal damage and killing two animals.

In the aftermath of these air raids, while falling short of their intended objectives, the Ottoman High Command was compelled to acknowledge that the peril posed exceeded their initial assessments. Subsequently, a responsive initiative materialized in the form of the establishment of a novel entity known as the Istanbul Command of Air Defense (İstanbul Muharebat-ı Havaiyye Komutanlığı). Simultaneously, a suite of measures aimed at safeguarding the civilian population was introduced. Regrettably, the efficacious implementation of these protective measures proved elusive, leading to the government facing vehement censure.

The year 1918 witnessed a pronounced escalation in aerial assaults directed at Istanbul and other coastal municipalities, including Izmir, Trabzon, Beirut, and Antalya. Notably, these assaults predominantly targeted military edifices and industrial installations, particularly munitions factories.

On 7 July 1918, five enemy aircraft conducted bombing raids on various strategic locations in Istanbul, targeting the munitions factory in Zeytinburnu, the train station in Haydarpaşa, and the Golden Horn, Selimiye, and Davutpaşa Barracks, as well as the Gülhane Gardens. Notably, these aerial assaults were an unprecedented occurrence for the citizens of Istanbul. Instead of seeking refuge in bunkers, a curious populace gravitated towards the streets to witness this extraordinary spectacle.

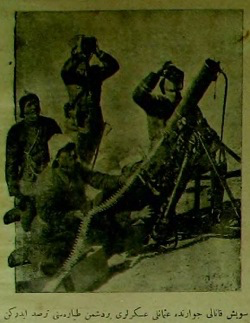

During subsequent raids in July and August 1918, the city experienced minimal damage. Concurrently, the Turkish forces honed their proficiency in aerial defense. A more adept intelligence network was instituted, facilitating early alerts regarding approaching adversary aircraft. As enemy planes approached, the entire city would be enveloped in darkness, while projector lights identified the aircraft, paving the way for intensified artillery barrages. Complementing the artillery efforts, the Turkish 9th Aircraft Squadron assumed responsibility for pursuing and engaging the enemy aircraft, contributing significantly to the city's defense.

The heightened efficacy in air defense manifested its consequential efficacy during the nocturnal assault of 27 August 1918, where British aerial units encountered impediments in reaching their designated objectives. A British aircraft succumbed to artillery fire during this engagement, resulting in the capture of the wounded British aviator. Notably, during this raid, four bombs descended upon the forecourt of the Ministry of Navy.

The impending culmination of the war prompted the Allies to intensify their efforts against the Ottoman Empire's capital. On 13 August, authorities instituted a fresh series of directives aimed at safeguarding the civilian populace. Citizens were enjoined to exercise heightened vigilance, particularly in guarding against potential espionage activities within the urban precincts that could compromise strategic targets.

On 20 and 21 September 1918, Allied forces conducted two aerial raids, departing from the Imbros base, aimed at demoralizing the inhabitants of Istanbul. The initial sortie refrained from deploying bombs, in contrast to the subsequent, more substantial wave. Turkish artillery downed one aircraft over Çanakkale during the second wave, yet the remaining squadron successfully reached Istanbul. Another aircraft sustained damage and was compelled to land in the waters near Kartal, resulting in the capture of two British airmen.

The most extensive air raid on Istanbul unfolded on 18 October 1918. In the morning's first wave, seven adversary planes menaced the city for twenty minutes, targeting the most densely populated thoroughfares. The afternoon witnessed a second wave, comprising five planes. These attacks claimed the lives of 70 civilians, while an additional 200 sustained injuries. Sultan Vahdettin sought refuge in a mosque during these assaults, as he found himself exposed to the bombings while en route for the Friday prayer.

The last air raid prior to the armistice occurred on 25 October 1918. Upon receiving intelligence regarding six British planes approaching from Çanakkale, four aircraft from the Turkish 9th Squadron, under the command of Captain Fazıl Bey, took flight. Among the accompanying pilots were Lieutenant Vecihi Bey, Austrian pilot Max Souchin, and a German pilot. Subsequently, the German and Austrian aviators fell behind, leaving Captain Fazıl Bey alone. Despite sustaining multiple bullet wounds, he successfully incapacitated a British observer and safely returned to Yeşilköy.

Shortly following this incident, the Ottoman Empire ratified the armistice, heralding the impending occupation of Istanbul by Allied forces.

![]()